(function(d, s, id) { var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = “https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v3.0”; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); }(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’)); –>

–>

December 25, 2023

Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol in 180 years old this year. Although many people today treat it as a child’s ghost story, it was originally written for — and continues to have — a very adult message. It has multiple layers of meaning. It is a masterpiece of a short story: as one commentator put it, who else could put the Grim Reaper (who else is the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come?) into a Christmas story and pull it off?

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”); } }); }); }

Let’s pick seven abiding themes of Carol that have something to say to grown-ups.

Your life is accountable. Although it’s not explicitly Christian, the Carol is very Christian in its perspective that you reap what you sow. We see that with the damned Jacob Marley. And it’s the central motif of Scrooge’s story: what he is has been influenced by the choices he made and, should be persist in them, “will foreshadow certain ends.” Life, in that sense, is very fair.

Death is the great equalizer. Carol’s three main characters all truck with death. Marley is a ghost, sent to warn Scrooge “you have yet a chance and hope of escaping my fate.” Scrooge toys with whether or not to mend his ways until the vision of his own tombstone disabuses his vacillations. And whether Tiny Tim lives or dies is the suspense on which our attention turns. As Hebrews reminds us, “it is appointed for men once to die…”

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”); } }); }); }

How you treat others is how you will be treated. Scrooge has no hesitation about pushing others aside, using them, treating them transactionally. But he never reckons with what goes around, comes around. Much of Scrooge’s shock at his future is just how dispensable and unneeded he is. His associates agree to attend his funeral on stipulation that they “must be fed,” only one volunteering to go without a meal. Wake beside his pilfered body is kept only by rats. Two debtors rejoice because his death buys them time to raise money; two charwomen rejoice because his death provides them with something to pawn. Scrooge is not so repulsed by an eternity of heaven or hell as a funeral of indifference.

Truth cannot be evaded. The Spirit of Christmas Past appears with a light shining from its head, something the initially bothers Scrooge and which he later crushes — driving away the Spirit — with a candle snuffer. “I bear the light of truth.” The light of truth forces Scrooge to face his past truthfully: those things that were done to him about which he was powerless (an uncaring father) as well as those he did by choice (his breakup with Belle). While Scrooge is ready to look at the past through selective, rose-colored glasses, the Spirit forces him to open his eyes, e.g., to see the impoverishment of his life against the rich happiness Belle found as a wife and mother with another man.

Truth cannot be evaded. The Spirit of Christmas Past appears with a light shining from its head, something the initially bothers Scrooge and which he later crushes — driving away the Spirit — with a candle snuffer. “I bear the light of truth.” The light of truth forces Scrooge to face his past truthfully: those things that were done to him about which he was powerless (an uncaring father) as well as those he did by choice (his breakup with Belle). While Scrooge is ready to look at the past through selective, rose-colored glasses, the Spirit forces him to open his eyes, e.g., to see the impoverishment of his life against the rich happiness Belle found as a wife and mother with another man.

Happiness doesn’t take much. Scrooge reflects on happy memories of Christmas balls as an apprentice at Fezziwig’s. The Ghost of Christmas Past challenges him: “He spent but a few pounds of your mortal money, three or four perhaps.” In the George C. Scott movie version, the Ghost says: “What did he do? Spend some money? Dance like a monkey?” And yet, decades later as we see that with Scrooge, memory of those three or four pounds is still compounding interest, albeit not a sum reckoned in a bankbook.

Now is the moment to bring happiness. In a scene often omitted from movie versions, Dickens describes what Scrooge sees after Marley leaves him. Marley exits from Scrooge’s window to join a chorus of damned spirits whose presence on Scrooge’s little street suddenly become apparent. He sees “one old ghost, in a white waistcoat, with a monstruous iron safe attached to its ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below, upon a door-step.” Dickens is blunt: “The misery with them all was… that they sought to interfere, for good in human matters, and had lost the power forever.” Life is when we can touch life, and life is fleeting.

Life is to be valued. Life is not just valued for its usefulness but because it is a gift about which we should not presume. Early on, when asked to contribute to poor relief, Scrooge is told some of the poor “would rather die.” “Then let them die and decrease the surplus population!” Later, when watching Tiny Tim, Scrooge expresses sympathy for the child, the Ghost of Christmas Present rebukes him with his own words. “It may be that in the sight of heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man’s child! …To hear the Insect on the leaf pronouncing on too much life among his hungry brothers in the dust!” How much of that rebuke might fit our anti-life, “quality of life” partisans who, like the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, opine on “populations we don’t want to have too many of.”

It’s said that, when he was in the White House, FDR would read the Carol aloud on Christmas Eve to his family. The kiddies may enjoy the ghosts and the scares and Tiny Tim and the eventual happy ending, but might be challenged by the original: Dickens was writing, after all, in 1843, when literacy rates and vocabulary comprehension were higher. But that’s perhaps all the more reason for the adults to sit down this holiday season with the original, unadulterated text and savor — nearly two centuries after Dickens put pen to paper — what lessons the Carol still speaks to the grown-ups in the room.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”); } }); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

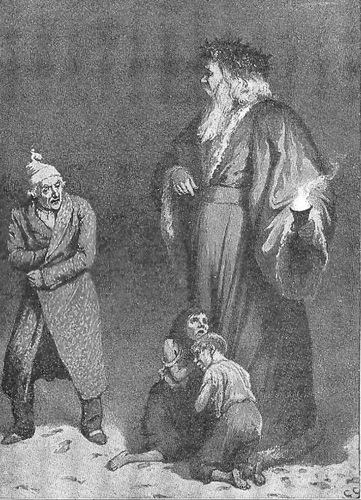

Image: Charles Green

<!–

–>

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>