By Benjamin Picton, Senior Macro Strategist at Rabobank

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back

The University of Michigan consumer survey released last Friday held good news for the economy that may be bad news for markets. Measures of consumer sentiment, current conditions and future expectations all surged. However, 1-year inflation expectations defied analyst predictions of a fall to rise by one tick on the month to 3.4%, while 5-10 year inflation expectations also nudged higher to 3.1%. The strong reading appears in contrast to the CPI inflation report released last week, which showed core inflation running two ticks lower than expected at 4.8% year-on-year and also puts further pressure on widespread expectations of impending recession.

10-year Treasury yields duly rose by almost 7bps to 3.83%, but remain well off the 4.08% highest close for the year that was recorded just ten days ago. Equity markets seem to be unsure what to make of it all. The NASDAQ closed down 0.18% while the lower beta Dow Jones index recorded a gain of 0.33%. Separating the signal from the noise here is difficult, but the overall impression is that the inflation battle has not yet been convincingly won.

As with many things, there is a world of contrast here between the United States and China. While markets were celebrating core inflation of *only* 4.8% last week, China was reporting consumer price growth of zero in June and accelerating producer price deflation.

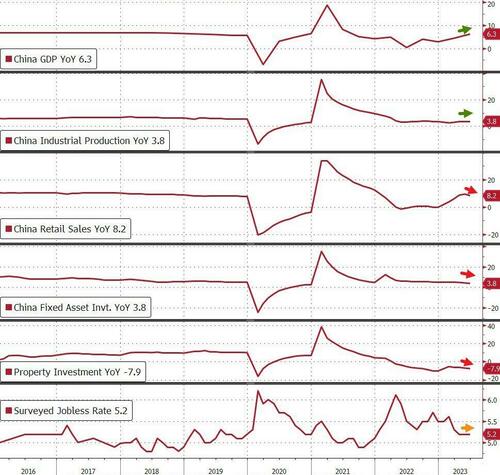

This rang some alarm bells in trade-exposed economies like Australia and New Zealand, where the financial press picked up on the poor figures to point out that demand for commodity exports looks dicey in the months ahead, but there remains a glimmer of hope from the efforts of the People’s Bank of China and the central government to reflate the economy via fiscal and monetary stimulus. Calls for stimulus will grow all the louder after this morning’s second quarter GDP figures showed the Chinese economy expanding 6.3% year-on-year. Much slower than the Bloomberg consensus estimate of 7.1%.

Recent PMI data from China shows that manufacturing remains under pressure and while the economy experienced a tailwind from re-opening after the Covid-zero policy was scrapped late last year, that boost now appears to be petering out. Trade figures released last week showed that Chinese imports contracted by 6.8% in the year to June, while exports fell a whopping 12.4%.

Rabobank’s China expert, Teeuwe Mevissen, has been clear that he expects that any stimulus efforts will be much more modest than we have seen in the past, owing to China’s troubles with high debt loads at the local government level and the smouldering real estate crisis that Xi Xinping has repeatedly failed to staunch through attempts to tighten bank credit standards. We expect that there could be some more targeted support for strategically important sectors (semiconductors?), which regular readers of the Daily may find reminiscent of Michael Every’s predictions of targeted liquidity, or as he puts it: “higher rates + acronyms”.

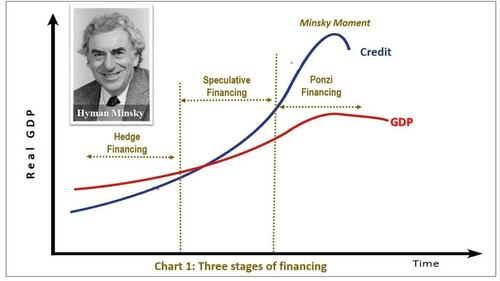

China is far from being Robinson Crusoe in dealing with issues in over-indebted real estate markets. Commercial real estate valuations in the West face something of a Waterloo moment as the cannonade of “return to office” is thwarted by the Prussian cavalry of increased bargaining power for workers, quiet-quitting and a discount rates that have leapt higher after 500bps worth of monetary tightening. Gillian Tett observes in the FT that $270bn of commercial real estate debt facilities are due to be refinanced this year, and up to $1.5trn over the next three years. Sinking valuations have been driven by lower demand for office space, which may mean that commercial real estate has shifted from Minsky’s definition of speculative financing (where cashflows on the asset are sufficient to meet financing liabilities, but not sufficient to repay the principal) to Ponzi-financing, whereby cashflows on the asset are no longer sufficient to repay principal OR interest charges under prevailing market rates. The implications for broader economic stability are enormous, and imply that the wobbles that we saw in the US banking sector earlier this year and the British pension system last year is not the end of the financial stability story.

This all leaves to one side what is going on in housing markets, where much of the attention continues to focus on the day-to-day plight of homeowners, rather than the broader macro stability picture. The RBNZ last week suggested in the Monetary Policy Statement that accompanied their decision to leave interest rates on hold that there was no conflict between the inflation mandate and the financial stability mandate. That seems divergent from the views of the Fed and the ECB, where interest rate decisions earlier in the year made it very clear that financial stability considerations did, in fact, inform how aggressive those central banks could be in achieving their inflation targets. In Australia, the RBA doesn’t even have a financial stability mandate. This responsibility was hived off to the banking regulator in the late 1990s, leaving the RBA only with a nebulous commitment to the “financial wellbeing of the Australian people”.

Housing market woes appear particularly acute in the UK, where there is a growing chorus of requests for government assistance with mortgage payments. Of course, the very idea of “mortgage relief” runs completely counter to the policy prescriptions of the Bank of England, who are now making the Sophie’s Choice between tightening monetary policy enough to force people out of their homes and businesses, or allowing inflation to continue to run out of control. So far, policy support has been limited to clearing obstacles to the “extend and pretend” approach, and we have seen longer mortgage terms becoming more and more prominent. However, the runway starts to run out when the term of the loan exceeds the reasonable working life of the borrower, or (as in the commercial real estate market) the underlying asset moves into negative equity. Rather than encouraging prudent deleveraging, politicians have in the past made absurd suggestions that the policy response to this could be shifting liabilities across generations. That sounds a bit like some kind of neo-serfdom.

Data released by RightMove this morning showing year-on-year house price growth in the UK has now slowed to just 0.5%, making negative equity a real risk for recent borrowers who took out loans with skinny deposits. If we’re now talking about granting mortgages of up to 50 years in term, and turning a blind eye to the credit implications of terming out loan commitments because the amortization schedule no longer sums with the borrower’s income, surely that means that housing markets are now well into Ponzi-financing territory? What happens when the unemployment rate rises, as every central bank is forecasting it will? If years of government “help” for first home buyers via lower deposit requirements coupled with absurdly cheap money from central banks has built a ‘Minsky Moment’ powder keg under the economy via unstable real estate markets, a monetary pause on the back of momentarily encouraging inflation readings may very well be a case of one step forward, two steps back.

By Benjamin Picton, Senior Macro Strategist at Rabobank

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back

The University of Michigan consumer survey released last Friday held good news for the economy that may be bad news for markets. Measures of consumer sentiment, current conditions and future expectations all surged. However, 1-year inflation expectations defied analyst predictions of a fall to rise by one tick on the month to 3.4%, while 5-10 year inflation expectations also nudged higher to 3.1%. The strong reading appears in contrast to the CPI inflation report released last week, which showed core inflation running two ticks lower than expected at 4.8% year-on-year and also puts further pressure on widespread expectations of impending recession.

10-year Treasury yields duly rose by almost 7bps to 3.83%, but remain well off the 4.08% highest close for the year that was recorded just ten days ago. Equity markets seem to be unsure what to make of it all. The NASDAQ closed down 0.18% while the lower beta Dow Jones index recorded a gain of 0.33%. Separating the signal from the noise here is difficult, but the overall impression is that the inflation battle has not yet been convincingly won.

As with many things, there is a world of contrast here between the United States and China. While markets were celebrating core inflation of *only* 4.8% last week, China was reporting consumer price growth of zero in June and accelerating producer price deflation.

This rang some alarm bells in trade-exposed economies like Australia and New Zealand, where the financial press picked up on the poor figures to point out that demand for commodity exports looks dicey in the months ahead, but there remains a glimmer of hope from the efforts of the People’s Bank of China and the central government to reflate the economy via fiscal and monetary stimulus. Calls for stimulus will grow all the louder after this morning’s second quarter GDP figures showed the Chinese economy expanding 6.3% year-on-year. Much slower than the Bloomberg consensus estimate of 7.1%.

Recent PMI data from China shows that manufacturing remains under pressure and while the economy experienced a tailwind from re-opening after the Covid-zero policy was scrapped late last year, that boost now appears to be petering out. Trade figures released last week showed that Chinese imports contracted by 6.8% in the year to June, while exports fell a whopping 12.4%.

Rabobank’s China expert, Teeuwe Mevissen, has been clear that he expects that any stimulus efforts will be much more modest than we have seen in the past, owing to China’s troubles with high debt loads at the local government level and the smouldering real estate crisis that Xi Xinping has repeatedly failed to staunch through attempts to tighten bank credit standards. We expect that there could be some more targeted support for strategically important sectors (semiconductors?), which regular readers of the Daily may find reminiscent of Michael Every’s predictions of targeted liquidity, or as he puts it: “higher rates + acronyms”.

China is far from being Robinson Crusoe in dealing with issues in over-indebted real estate markets. Commercial real estate valuations in the West face something of a Waterloo moment as the cannonade of “return to office” is thwarted by the Prussian cavalry of increased bargaining power for workers, quiet-quitting and a discount rates that have leapt higher after 500bps worth of monetary tightening. Gillian Tett observes in the FT that $270bn of commercial real estate debt facilities are due to be refinanced this year, and up to $1.5trn over the next three years. Sinking valuations have been driven by lower demand for office space, which may mean that commercial real estate has shifted from Minsky’s definition of speculative financing (where cashflows on the asset are sufficient to meet financing liabilities, but not sufficient to repay the principal) to Ponzi-financing, whereby cashflows on the asset are no longer sufficient to repay principal OR interest charges under prevailing market rates. The implications for broader economic stability are enormous, and imply that the wobbles that we saw in the US banking sector earlier this year and the British pension system last year is not the end of the financial stability story.

This all leaves to one side what is going on in housing markets, where much of the attention continues to focus on the day-to-day plight of homeowners, rather than the broader macro stability picture. The RBNZ last week suggested in the Monetary Policy Statement that accompanied their decision to leave interest rates on hold that there was no conflict between the inflation mandate and the financial stability mandate. That seems divergent from the views of the Fed and the ECB, where interest rate decisions earlier in the year made it very clear that financial stability considerations did, in fact, inform how aggressive those central banks could be in achieving their inflation targets. In Australia, the RBA doesn’t even have a financial stability mandate. This responsibility was hived off to the banking regulator in the late 1990s, leaving the RBA only with a nebulous commitment to the “financial wellbeing of the Australian people”.

Housing market woes appear particularly acute in the UK, where there is a growing chorus of requests for government assistance with mortgage payments. Of course, the very idea of “mortgage relief” runs completely counter to the policy prescriptions of the Bank of England, who are now making the Sophie’s Choice between tightening monetary policy enough to force people out of their homes and businesses, or allowing inflation to continue to run out of control. So far, policy support has been limited to clearing obstacles to the “extend and pretend” approach, and we have seen longer mortgage terms becoming more and more prominent. However, the runway starts to run out when the term of the loan exceeds the reasonable working life of the borrower, or (as in the commercial real estate market) the underlying asset moves into negative equity. Rather than encouraging prudent deleveraging, politicians have in the past made absurd suggestions that the policy response to this could be shifting liabilities across generations. That sounds a bit like some kind of neo-serfdom.

Data released by RightMove this morning showing year-on-year house price growth in the UK has now slowed to just 0.5%, making negative equity a real risk for recent borrowers who took out loans with skinny deposits. If we’re now talking about granting mortgages of up to 50 years in term, and turning a blind eye to the credit implications of terming out loan commitments because the amortization schedule no longer sums with the borrower’s income, surely that means that housing markets are now well into Ponzi-financing territory? What happens when the unemployment rate rises, as every central bank is forecasting it will? If years of government “help” for first home buyers via lower deposit requirements coupled with absurdly cheap money from central banks has built a ‘Minsky Moment’ powder keg under the economy via unstable real estate markets, a monetary pause on the back of momentarily encouraging inflation readings may very well be a case of one step forward, two steps back.

Loading…