–>

May 25, 2023

Global warming completely stopped in 2018. Temperatures will likely remain steady until 2025 and may decline slightly by 2030. A strong El Niño in 2023 is unlikely. I’ll explain all of my predictions — after we hear from the experts.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”); } }); }); }

NOAA recently predicted a 55% chance of a strong El Niño in late 2023. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) threw more fuel on the fire when it announced, “There is a 98% likelihood that at least one of the next five years, and the five-year period as a whole, will be the warmest on record.” Obviously, the MSM had a field day with this. Take for example this headline from USA Today: “Scientists warn an El Niño is likely coming that could bring scorching heat to Earth.”

Rather than taking the well worn path of pointing out flaws in the predictions of NOAA, the IPCC, or the WMO, I’ll instead show how the sun is likely responsible for almost every detail in global temperatures over the last 125 years, and that it is also responsible for triggering strong El Niños.

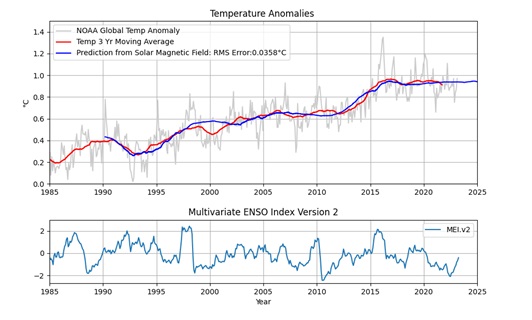

Two empirical, or black-box, models were created to predict global temperature. The first model uses solar magnetic field data from the Wilcox Solar Observatory (WSO). The second model uses sunspot data from WDC-SILSO, the Royal Observatory of Belgium, Brussels. Both predictions will be compared to global temperature anomaly data from NOAA.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”); } }); }); }

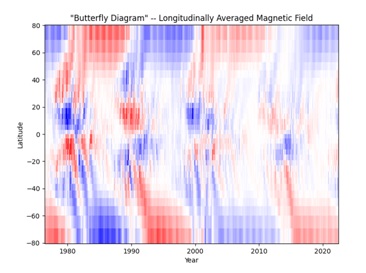

Solar magnetic field data collection began in 1976. The complete WSO dataset can be viewed in a single graphic, often referred to as a butterfly diagram. It looks complicated, but it’s really not. It’s just a plot of solar magnetic field intensity over time as a function of the sun’s latitude. The two colors represent north and south polarity magnetism. Unlike the Earth, where magnetic north has conveniently stayed in the Northern Hemisphere for the last 780,000 years, the sun’s magnetic field changes polarity every 11 years.

Notice how the colors fade from left to right? That’s the sun’s magnetic field getting weaker with time. As the sun’s magnetic field weakened, the Earth warmed. Why? Well, I can’t answer that — nobody can — but with weaker magnetic fields, there’s more interaction between the atmosphere and galactic cosmic rays (CGRs). There are several, complicated, and often competing theories on how these interactions affect climate. As we tend to associate lower solar activity with cooling, not warming, as shown here, the sun’s total solar irradiance (TSI) likely plays a significant longer-term role in global temperatures. TSI hasn’t changed much over the short amount of time we’ve been able to reliably measure it, so TSI is not included in either model.

Using only the data shown in the butterfly diagram, it’s possible to predict temperature with a simple 11-year moving average to smooth out the 11-year cycles. The averaged data is then negated to account for weaker magnetic fields causing rising temperatures, shifted forward by 2.8 years to account for the Earth’s delayed global response to the sun, and finally scaled to convert from units of Tesla to degrees. Since we know what the sun is doing now, we can predict how the Earth will respond 2.8 years from now. That’s it! A little data-smoothing and a minus sign. It’s not a very complicated model.

Note how closely the average global temperature tracks the predicted temperature. We’ll see this same two-step temperature change shape again with the longer sunspot-based model. Without the minus sign, one might conclude that the sun doesn’t cause global warming.

Here’s what the sun can tell us about the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). NOAA’s ENSO index shows two strong El Niño events starting in 1997 and 2015 (El Niño events are positive values and La Niña events negative). As predicted by the model, prior to both events, global temperatures rose dramatically. This is a key point. Rapid sun-induced warming triggers strong El Niños. El Niños don’t cause global warming, and they most certainly don’t affect the sun’s magnetic fields. The correct order of causality is sun → global temperatures → strong climate oscillations.

The magnetic field model predicts stable temperatures until 2025, so while there could be an El Niño event later this year, as predicted by NOAA, solar history suggests that the event would likely be mild-to-moderate. In particular, the small ENSO around 2009 seems to be more in keeping with the steady temperatures we’re currently experiencing. This type of El Niño will affect local climates but will likely cause only a small ripple in global temperatures.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”); } }); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

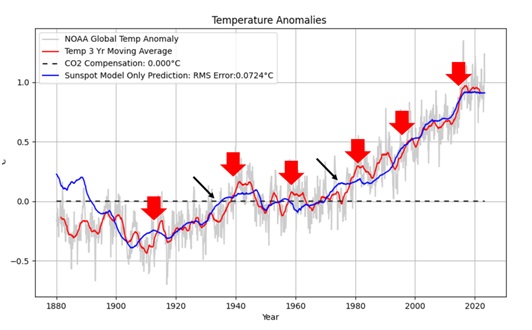

Using sunspot data as a proxy for solar activity, it’s possible to extend accurate temperature predictions back to 1900. Whereas the magnetic field model was only 11 years long, the sunspot model varies in length between 99 and 126 years, depending on the model variant. This increased length allows the model to extract information from the longer solar cycles (which also drive TSI).

To explain a lack of prediction accuracy, greenhouse gas models tend to require a lot of help from pollution, buckets, volcanos, fires, data refinements, and climate oscillations. This is especially true over the last eight years where temperatures have not followed the exponential rise in CO2 contributions.

Without any extra help, the sunspot-based model correctly predicts falling temperatures to 1910, rising temperatures to 1947, slightly declining temperatures to 1970, rising temperatures to 2012, slowly rising temperatures to 2018, and steady or slightly declining temperatures to date. The other model variants predict steady, or slightly declining temperatures to 2030.

The model does support the inclusion of a simple CO2 warming model. While the use of both models does have a slightly lower error with 0.2°C of CO2 warming, the CO2 model is likely just correcting for sunspot model inaccuracy in the years prior to 1910. Here, CO2 compensation is disabled.

Strong El Niño events are indicated by the red arrows. In all cases, the strong El Niños are preceded by a sudden rise in the predicted temperature. The two strongest events occurred in 1940 and 1982. Black arrows indicate the solar events that appear to have triggered them.

These models predict that global temperatures will remain steady or decline slightly. Deep ocean temperatures will continue to rise, ice may continue to melt, and local temperature records may be set — at least until a new equilibrium is reached, or temperatures begin to fall. The models also predict that fear-mongering climate change headlines will continue until politicians start claiming victory for having saved us all from global warming.

For complete transparency, the models and code used predict global temperature from sunspots and solar magnetism are available here.

Robert Cutler is an engineer with decades of experience in signal analysis.

Image: kie-ker via Pixabay, Pixabay License.

<!–

–>

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>