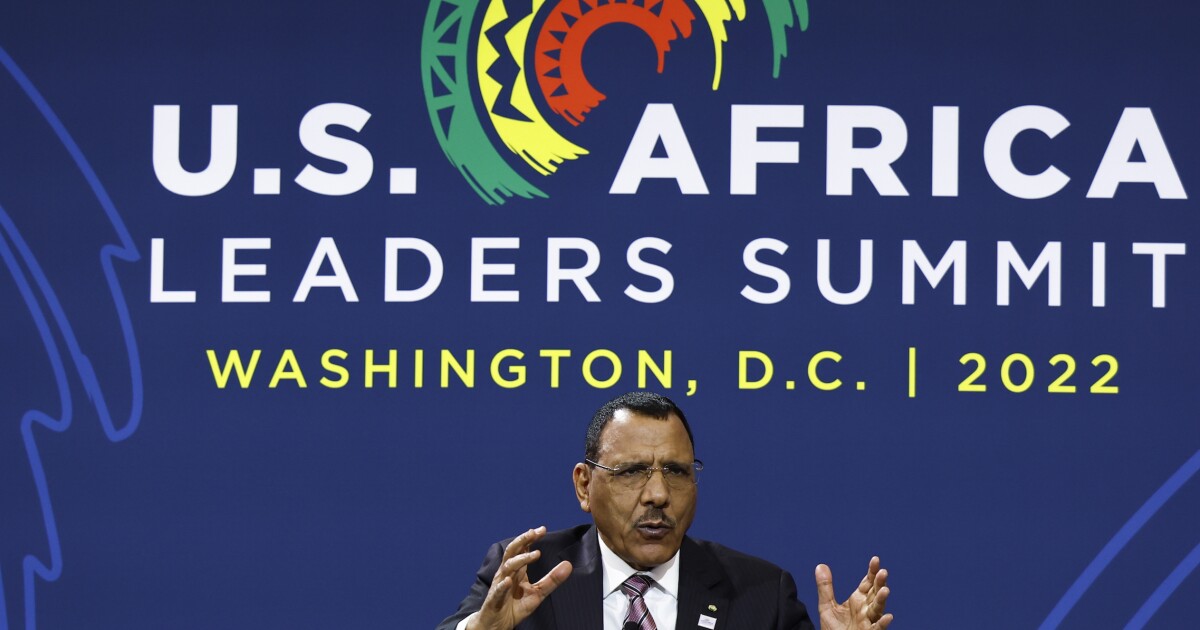

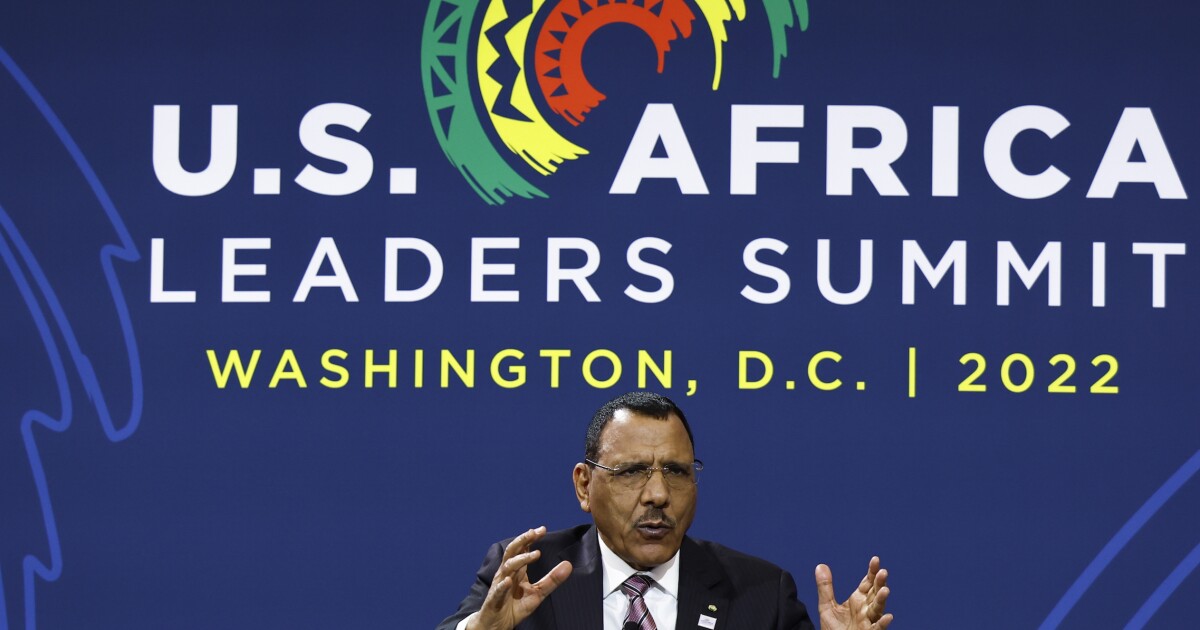

Nigerien President Mohamed Bazoum is on a mission to build about 46,000 schools in his country, which has one of lowest literacy rates in the world — and a population expected to nearly triple by 2050.

“Success is very slow,” Bazoum acknowledged in an interview with the Washington Examiner. “We’re still at the beginning stages of this activity. So it will take some time. And, we need more resources.”

The experience of Niger, a French-speaking country of 25 million West Africans with a literacy rate below 14%, is an extreme case but still emblematic of a wider dynamic across the continent. The population of sub-Saharan Africa is expected to grow by about 1 billion people by 2050. In that time frame, Nigeria, the English-speaking country between Niger and the Atlantic coastline, will see its population grow from about 216 million to 375 million people, according to U.N. estimates.

“The people are the wealth of Africa,” United States Institute of Peace senior fellow Tom Sheehy told the Washington Examiner. “They’ve got a lot of natural resources, but ultimately, if they’re going to develop, it’s going to be through human capital. And it’s a big, big test educating people in a resource shortage.”

US CHALLENGES CHINA’S GROWING INFLUENCE IN AFRICA WITH HIGH-STAKES INVESTMENTS

Nigeria alone is on pace to stand as one of the four most populous countries in the world by 2050, according to the United Nations. The human and geopolitical potential contained in that data can be inferred from the international heavyweights that also appear atop the population rankings — China, India, and the United States. Such growth could “certainly” represent an advantage for African societies almost unrivaled in the world but only in the right circumstances.

“On condition that we really focus on education and development of young people by providing them with the skills they need,” Bazoum said. “But if you have a lot of people that are uneducated, they constitute a danger. Seen from that angle, the future of Africa is not bright because if the population is not educated, the population is not an asset for Africa. Rather, it can be a handicap for Africa.”

An effective education system can affect the character of civil society, he added. “Certainly, education is key in creating an informed society, aware of its rights, its duties,” Bazoum said.

“And, of course, the key element for a democracy to thrive is to have well-educated people that know their rights but [also] know what they should do and what they should not do and that we create a national consciousness in terms of citizenship.”

With that in mind, education would seem like a high-value sector for countries keen to support African development or cultivate influence on the continent. The world’s global heavyweights, including China and the United States, recognize Africa has a major economic and geopolitical frontier — but there persists a paradoxical lack of investment in African education, at least in comparison to other forms of engagement.

“I don’t think that foresight is there to make those investments in human capital in developing countries in Africa,” said Dr. Malancha Chakrabarty, an expert in African development at the India-based Observer Research Foundation. “There’s a tendency to call it social sector … the relatively softer things which everybody believes is nice, but very little sums of money or resources are actually put into it.”

Bazoum credited the U.S. with contributing to infrastructure development in Niger, such as the construction of roads and the modernization of the agriculture sector, which he listed alongside education as a top priority for his administration. Several European countries, especially France, have provided more direct assistance to his education program.

“For the Nigerien government, education and vocational training are also two priorities to develop human capital. To this end, France is financing several actions in Niger,” a French official said.

“The ‘Women Teachers and Girls’ Education in Africa’ initiative: This project is based on the establishment of a virtuous circle whereby African women teachers and education managers develop professional, technical, and social skills that strengthen their leadership,” the French official added. “In turn, they will be able to serve as role models for girls, supporting them in their learning and developing their capacity. The project targets nine countries in Africa, including Niger.”

Education does appear among the priorities to benefit from the $55 billion in aid that President Joe Biden touted at the U.S.-Africa Leader Summit in Washington.

“They involve a wide range of sectors that reflect our shared interest and renewed partnerships — sectors such as food security, health, climate, trade and investment, economic growth, and also education, peace and security, and democracy,” State Department Undersecretary Jose Fernandez told journalists on Tuesday. “It also aims to leverage the best of America that we have to offer — our civil society, our private sector, our government institutions — in order to partner with African countries to meet today’s defining challenges and opportunities.”

The scale of population growth in Africa raises the possibility for countries there to alter the balance of political and economic power in a world that pays more attention to the Indo-Pacific, with its powerhouse economies and risk of war between the U.S. and China — but only if allies and development partners increase their attention to “the impact of education on human development,” according to Chakrabarty.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“At the end of the day, any development rests on the quality of the people of that particular country,” she said. “You might have short spurts of growth, and that growth could come from any … sector of the economy. But true development or long-term development is impossible without serious and adequate spending on education.”