Two days ago, markets exhaled a collective breath of relief when China published its monthly data dump which disclosed that in addition to beating (almost) across the board for retail sales, industrial output, and fixed investment, the country's GDP came well above expectations of 4.50%, printing at a 4.90% increase YoY.

This was good news for a world starved for any positive developments out of China, and Chinese assets promptly bounced (if only to sink shortly after as attention return to China's rapidly disintegrating property sector). There is just one problem: as with every economic data coming out of China (and lately the US, as well), this was a lie.

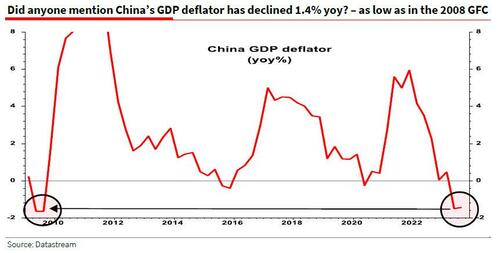

While it is true that reported real GDP was 4.9%, what SocGen's Albert Edwards points out in his latest Global Strategy Weekly note is that this was only possible because the Chinese economy remained in deflation in Q3, hardly an indication of economic prosperity.

As Edwards explains, the 4.9% upside surprise on real GDP was "only achieved because of the surprisingly sharp 1.4% fall in the GDP deflator – that was then added to weak 3.5% nominal GDP growth."

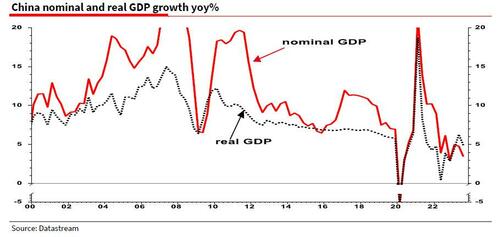

This is a problem because as the SocGen strategist observes next, "nominal GDP growth in China at 3.5% (red line in chart below) is far lower than the pre-Covid run rate compared to real GDP." And since "it is the nominal pulse that is accurately measured" what matters is the nominal print. Then after statisticians make some informed guesses as to what prices are doing, ‘real’ constant price GDP pops up in the spreadsheet.

Hence for China to meet its 5% ‘real’ GDP target, Edwards sarcastically explains, "merely requires the statisticians to ‘assume’ prices are falling sharply. Hey, maybe there isn’t a Chinese deflation problem after all? But if so, that means real GDP growth is much weaker than is being officially reported."

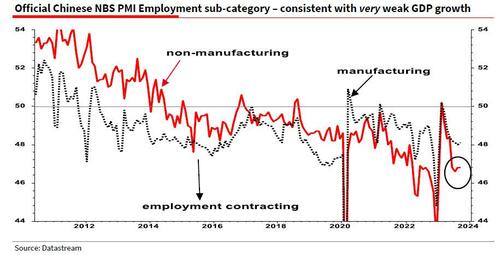

Edwards skepticism is corroborated by the far more accurate, PMI data, which signals "worryingly low employment in the non-manufacturing sector with no lockdowns to blame."

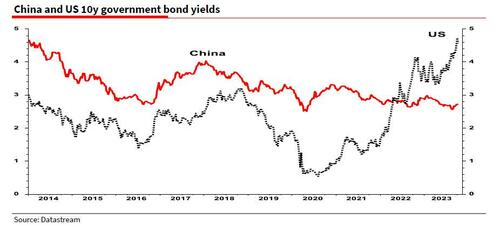

No wonder then that China 10y bond yields remain near an all time low level of 2.7%, in stark contrast to the US’s 4.99%.

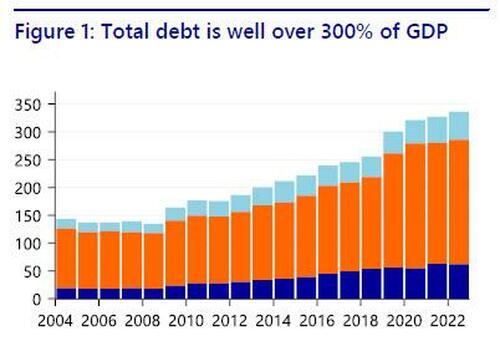

But if the Chniese data is again much weaker than indicated, what does that mean about Beijing's attempts to kickstart the economy and stimulate it out of its Japanification phase? Well, as Edwards explains, "the Chinese authorities have been in easing mode recently, but the degree of easing can be described as support for the economy rather than stimulus" which is what one would expect from a country that has a record 300%+ debt/GDP: this is where the tire meets the road for all those idiot MMT fans whose entire monetary religion goes up in a small puff of smoke once debt becomes the gating factor as it has in China.

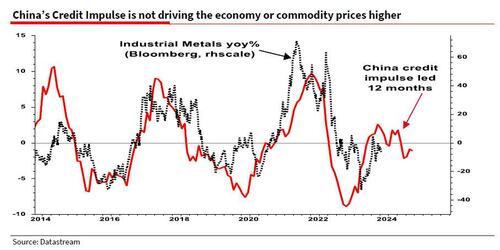

That is why, according to Albert, you see industrial metals limping along (more zombie analogies?) rather than sprinting ahead.

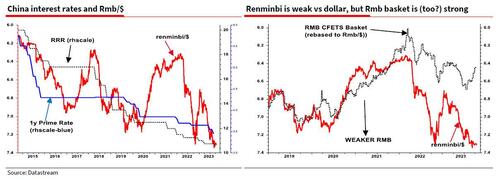

Looking ahead, fake data aside, SocGen's China economists expect one more cut in rates this year, but another problem emerges: China’s recent rate cuts – in stark contrast to the US – are putting the renminbi under heavy downward pressure (left chart below). Nevertheless, the renminbi basket has been rebounding recently and stands close to a Rmb6.4/$ equivalent (see right hand chart).

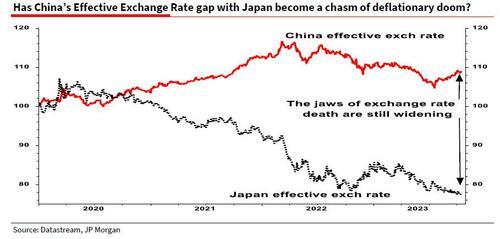

Which brings us to Edwards' conclusion which touches on a topic we recently mentioned on twitter, namely that the most important currency pair does not even have the dollar in it, but rather is the interplay between two export powerhouses: China and Japan...

The most important FX pair is also the one nobody is looking at. pic.twitter.com/692YnvklvT

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) October 2, 2023

... or as Edwards puts it, "the gap between China’s exchange rate and the yen has become a chasm in recent years, despite Japan also pursuing easy money. China’s tight exchange rate policy is relatively deflationary. Maybe the falling deflator is right after all?"

The SocGen bear's parting words are spot on: this is a "situation that needs very close watching."

More in the full note available to pro subs in the usual place.

Two days ago, markets exhaled a collective breath of relief when China published its monthly data dump which disclosed that in addition to beating (almost) across the board for retail sales, industrial output, and fixed investment, the country’s GDP came well above expectations of 4.50%, printing at a 4.90% increase YoY.

This was good news for a world starved for any positive developments out of China, and Chinese assets promptly bounced (if only to sink shortly after as attention return to China’s rapidly disintegrating property sector). There is just one problem: as with every economic data coming out of China (and lately the US, as well), this was a lie.

While it is true that reported real GDP was 4.9%, what SocGen’s Albert Edwards points out in his latest Global Strategy Weekly note is that this was only possible because the Chinese economy remained in deflation in Q3, hardly an indication of economic prosperity.

As Edwards explains, the 4.9% upside surprise on real GDP was “only achieved because of the surprisingly sharp 1.4% fall in the GDP deflator – that was then added to weak 3.5% nominal GDP growth.”

This is a problem because as the SocGen strategist observes next, “nominal GDP growth in China at 3.5% (red line in chart below) is far lower than the pre-Covid run rate compared to real GDP.” And since “it is the nominal pulse that is accurately measured” what matters is the nominal print. Then after statisticians make some informed guesses as to what prices are doing, ‘real’ constant price GDP pops up in the spreadsheet.

Hence for China to meet its 5% ‘real’ GDP target, Edwards sarcastically explains, “merely requires the statisticians to ‘assume’ prices are falling sharply. Hey, maybe there isn’t a Chinese deflation problem after all? But if so, that means real GDP growth is much weaker than is being officially reported.“

Edwards skepticism is corroborated by the far more accurate, PMI data, which signals “worryingly low employment in the non-manufacturing sector with no lockdowns to blame.”

No wonder then that China 10y bond yields remain near an all time low level of 2.7%, in stark contrast to the US’s 4.99%.

But if the Chniese data is again much weaker than indicated, what does that mean about Beijing’s attempts to kickstart the economy and stimulate it out of its Japanification phase? Well, as Edwards explains, “the Chinese authorities have been in easing mode recently, but the degree of easing can be described as support for the economy rather than stimulus” which is what one would expect from a country that has a record 300%+ debt/GDP: this is where the tire meets the road for all those idiot MMT fans whose entire monetary religion goes up in a small puff of smoke once debt becomes the gating factor as it has in China.

That is why, according to Albert, you see industrial metals limping along (more zombie analogies?) rather than sprinting ahead.

Looking ahead, fake data aside, SocGen’s China economists expect one more cut in rates this year, but another problem emerges: China’s recent rate cuts – in stark contrast to the US – are putting the renminbi under heavy downward pressure (left chart below). Nevertheless, the renminbi basket has been rebounding recently and stands close to a Rmb6.4/$ equivalent (see right hand chart).

Which brings us to Edwards’ conclusion which touches on a topic we recently mentioned on twitter, namely that the most important currency pair does not even have the dollar in it, but rather is the interplay between two export powerhouses: China and Japan…

The most important FX pair is also the one nobody is looking at. pic.twitter.com/692YnvklvT

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) October 2, 2023

… or as Edwards puts it, “the gap between China’s exchange rate and the yen has become a chasm in recent years, despite Japan also pursuing easy money. China’s tight exchange rate policy is relatively deflationary. Maybe the falling deflator is right after all?”

The SocGen bear’s parting words are spot on: this is a “situation that needs very close watching.”

More in the full note available to pro subs in the usual place.

Loading…