By Simon White, Bloomberg Markets Live analyst and reporter

Forward earnings remain elevated, but profit estimates are most wrong when recessions hit. As recession risk rises, more timely indicators are pointing to the likelihood of an earnings recession later this year.

Earnings, and what investors will pay for them, i.e. the P/E ratio, are over time the largest contribution to stocks’ total returns. The fall in the latter has been the main driver of lower returns this year. But multiples are now off 40% from their highs, while earnings have yet to contribute negatively.

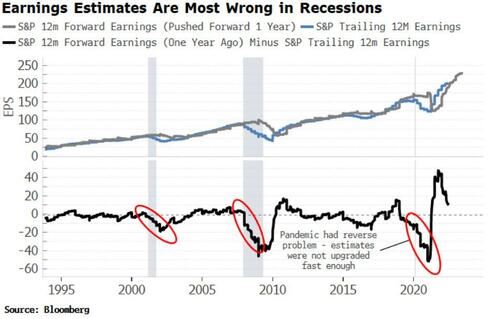

Using forward earnings to gauge what is going to happen to profits might get you by in times of calm, yet it is a poor policy when recession risk is heightened. The chart below shows 12-month forward earnings pushed forward one year versus trailing 12-month ones. This allows us to see the “surprise” between expected and actual earnings.

Outside of recessions, the black line in the chart doesn’t stray too far from zero. But during recessions we see that actual earnings are considerably worse than expected ones.

This is a problem not only confined to equities. Economic data are typically most wrong at major turning points such as recessions. Ironically, though, this is when you need most clarity.

Forward earnings for the S&P have been falling this year, but if the past is a guide they are still likely to be too optimistic. As Morgan Stanley’s CIO of Wealth Management Lisa Shalett put it, “Analysts are still in fantasy land in terms of the earnings outlook.”

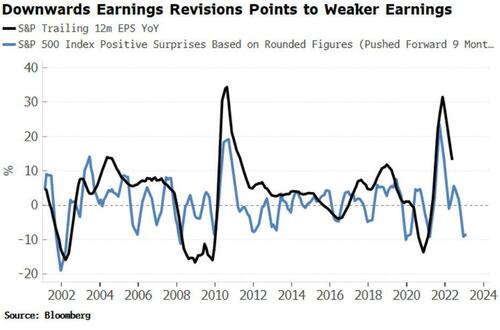

Step back from forward earnings, and the outlook is clouding. Better than relying on estimates is tracking the number of analyst upgrades in the aggregate. The fall in upgrades/rise in downgrades points to much weaker earnings growth over the next 6-9 months.

The poor earnings outlook is corroborated by a swathe of macro data, from a decline in corporate confidence, to the rise in the dollar, and to the very tight job markets fueling employment costs much higher.

By Simon White, Bloomberg Markets Live analyst and reporter

Forward earnings remain elevated, but profit estimates are most wrong when recessions hit. As recession risk rises, more timely indicators are pointing to the likelihood of an earnings recession later this year.

Earnings, and what investors will pay for them, i.e. the P/E ratio, are over time the largest contribution to stocks’ total returns. The fall in the latter has been the main driver of lower returns this year. But multiples are now off 40% from their highs, while earnings have yet to contribute negatively.

Using forward earnings to gauge what is going to happen to profits might get you by in times of calm, yet it is a poor policy when recession risk is heightened. The chart below shows 12-month forward earnings pushed forward one year versus trailing 12-month ones. This allows us to see the “surprise” between expected and actual earnings.

Outside of recessions, the black line in the chart doesn’t stray too far from zero. But during recessions we see that actual earnings are considerably worse than expected ones.

This is a problem not only confined to equities. Economic data are typically most wrong at major turning points such as recessions. Ironically, though, this is when you need most clarity.

Forward earnings for the S&P have been falling this year, but if the past is a guide they are still likely to be too optimistic. As Morgan Stanley’s CIO of Wealth Management Lisa Shalett put it, “Analysts are still in fantasy land in terms of the earnings outlook.”

Step back from forward earnings, and the outlook is clouding. Better than relying on estimates is tracking the number of analyst upgrades in the aggregate. The fall in upgrades/rise in downgrades points to much weaker earnings growth over the next 6-9 months.

The poor earnings outlook is corroborated by a swathe of macro data, from a decline in corporate confidence, to the rise in the dollar, and to the very tight job markets fueling employment costs much higher.