By Seth Carpenter, Morgan Stanley Chief Global Economist and former Fed economist

Quantitative easing (QE) changed central bank balance sheets forever. In August 2007, the Fed’s balance sheet was about $900 billion; this year, it peaked at $9 trillion. The global rates sell-off makes investors look at their P&Ls, and I am getting more questions about central bank P&Ls...a topic I have thought about for a while. Central banks will not go bankrupt, but it is worth considering when losses do and do not matter.

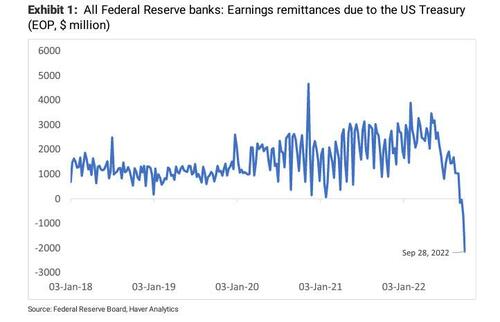

Starting with the Fed, all the income generated on the System Open Market Account portfolio, less interest expense, realized losses, and operating costs is remitted to the US Treasury. Before the Global Financial Crisis, these remittances averaged $20-25 billion per year; they ballooned to more than $100 billion as the balance sheet grew. These remittances reduce the deficit and borrowing needs. Net income depends on the (mostly fixed) average coupon on assets, the share of liabilities that are interest free (physical paper currency), and the level of reserves and reverse repo balances, whose costs float with the policy rate. From essentially zero in 2007, interest-bearing liabilities have mushroomed to almost two-thirds of the balance sheet. As Exhibit 1 shows, the Fed’s net income has turned negative, and losses will deepen as the policy rate rises. Because the Fed – like most central banks – does not mark its assets to market, losses on the portfolio are unrealized and do not flow through the income statement (although for transparency’s sake, the Fed publishes the unrealized gain/loss position on its portfolio quarterly). But if the Fed sells assets, the losses are realized, reducing net income.

So, what do losses mean? Is there a hit to capital? Bankruptcy? An inability to conduct monetary policy? No. First, remittances to the Treasury end, and the Treasury issues more debt. The Fed then cumulates its losses and, rather than reducing its capital, creates a “deferred asset.”(The details are tedious. On the weekly H.4.1, a negative liability is reported, but in the financial statement, it is an asset.) When earnings turn positive again, remittances stay at zero until the losses are recouped; imagine the Fed facing a 100% tax rate and offsetting current losses with future income. Profitability will eventually return because currency will keep growing, lowering interest expense, and QT will shrink interest-bearing liabilities.

There are global variations on this theme. The Bank of England has an explicit indemnification agreement with His Majesty’s Treasury for losses on QE. The effect is essentially the same as with the Fed, but the political economy differs. Where HMT and the BoE share responsibility, the Fed is on its own. Passive unwinding for the BoE is hard, given the lumpy maturity structure of gilt holdings, while the Fed has up to $95 billion per month running off passively. For the BoE, a one percentage point increase in Bank Rate lowers remittances by roughly £10 billion per year, a material sum for a country grappling with fiscal issues. The proposal to lower expense by prohibiting interest payments on reserves deserves scrutiny. If no authority remains, the BoE would have to sell assets to regain monetary control, realizing losses. The losses exist; it is the timing that is in question.

The ECB’s balance sheet is structured quite differently, but the logic is similar. Our European team projects the depo rate at 2.5% by next March, which implies ECB losses of around €40 billion next year. Bank deposits receive the depo rate, which will be much higher than the yield on the portfolio. The BoJ’s balance sheet has similarly swelled, but as of March (the latest available data), the BoJ was in an unrealized gain position. We think that yield curve control (YCC) will be maintained through the end of Governor Kuroda’s term, but when it ends, if the JGB curve sells off sharply, the losses could be large, though unrealized.

The most interesting variant is the Czech National Bank. The CNB has had a negative equity position for most of the past 20 years. Managing a small, open economy means focusing on the exchange rate, and most assets are foreign currency-denominated. If the central bank is credible and the Czech koruna rises, the value of its assets falls. The same is true for the Swiss National Bank, whose profits and losses have swung by billions in some years, yet it has not lost control of policy.

Central bank profits and losses matter…but only when they matter. Before the 1900s, the subject of economics was called “political economy.” Central bank losses that affect fiscal outcomes may have political ramifications, but the banks' ability to conduct policy is not impaired.

By Seth Carpenter, Morgan Stanley Chief Global Economist and former Fed economist

Quantitative easing (QE) changed central bank balance sheets forever. In August 2007, the Fed’s balance sheet was about $900 billion; this year, it peaked at $9 trillion. The global rates sell-off makes investors look at their P&Ls, and I am getting more questions about central bank P&Ls…a topic I have thought about for a while. Central banks will not go bankrupt, but it is worth considering when losses do and do not matter.

Starting with the Fed, all the income generated on the System Open Market Account portfolio, less interest expense, realized losses, and operating costs is remitted to the US Treasury. Before the Global Financial Crisis, these remittances averaged $20-25 billion per year; they ballooned to more than $100 billion as the balance sheet grew. These remittances reduce the deficit and borrowing needs. Net income depends on the (mostly fixed) average coupon on assets, the share of liabilities that are interest free (physical paper currency), and the level of reserves and reverse repo balances, whose costs float with the policy rate. From essentially zero in 2007, interest-bearing liabilities have mushroomed to almost two-thirds of the balance sheet. As Exhibit 1 shows, the Fed’s net income has turned negative, and losses will deepen as the policy rate rises. Because the Fed – like most central banks – does not mark its assets to market, losses on the portfolio are unrealized and do not flow through the income statement (although for transparency’s sake, the Fed publishes the unrealized gain/loss position on its portfolio quarterly). But if the Fed sells assets, the losses are realized, reducing net income.

So, what do losses mean? Is there a hit to capital? Bankruptcy? An inability to conduct monetary policy? No. First, remittances to the Treasury end, and the Treasury issues more debt. The Fed then cumulates its losses and, rather than reducing its capital, creates a “deferred asset.”(The details are tedious. On the weekly H.4.1, a negative liability is reported, but in the financial statement, it is an asset.) When earnings turn positive again, remittances stay at zero until the losses are recouped; imagine the Fed facing a 100% tax rate and offsetting current losses with future income. Profitability will eventually return because currency will keep growing, lowering interest expense, and QT will shrink interest-bearing liabilities.

There are global variations on this theme. The Bank of England has an explicit indemnification agreement with His Majesty’s Treasury for losses on QE. The effect is essentially the same as with the Fed, but the political economy differs. Where HMT and the BoE share responsibility, the Fed is on its own. Passive unwinding for the BoE is hard, given the lumpy maturity structure of gilt holdings, while the Fed has up to $95 billion per month running off passively. For the BoE, a one percentage point increase in Bank Rate lowers remittances by roughly £10 billion per year, a material sum for a country grappling with fiscal issues. The proposal to lower expense by prohibiting interest payments on reserves deserves scrutiny. If no authority remains, the BoE would have to sell assets to regain monetary control, realizing losses. The losses exist; it is the timing that is in question.

The ECB’s balance sheet is structured quite differently, but the logic is similar. Our European team projects the depo rate at 2.5% by next March, which implies ECB losses of around €40 billion next year. Bank deposits receive the depo rate, which will be much higher than the yield on the portfolio. The BoJ’s balance sheet has similarly swelled, but as of March (the latest available data), the BoJ was in an unrealized gain position. We think that yield curve control (YCC) will be maintained through the end of Governor Kuroda’s term, but when it ends, if the JGB curve sells off sharply, the losses could be large, though unrealized.

The most interesting variant is the Czech National Bank. The CNB has had a negative equity position for most of the past 20 years. Managing a small, open economy means focusing on the exchange rate, and most assets are foreign currency-denominated. If the central bank is credible and the Czech koruna rises, the value of its assets falls. The same is true for the Swiss National Bank, whose profits and losses have swung by billions in some years, yet it has not lost control of policy.

Central bank profits and losses matter…but only when they matter. Before the 1900s, the subject of economics was called “political economy.” Central bank losses that affect fiscal outcomes may have political ramifications, but the banks’ ability to conduct policy is not impaired.