Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

The largest firms in the US are unsurpassably pulling ahead of their smaller rivals by earning more, investing more, holding more cash and buying back more of their stock.

The bull market is thus likely to remain historically lackluster and less robust as smaller companies continue to lag their bigger counterparts.

They say the rich get richer, and nowhere is that more true than for the most-valuable firms in the US. The “Magnificent Seven” is by now a well-worn moniker for a septet of some of the biggest companies in the world, such as Nvidia, Apple and Amazon.

Yet the widening leadership that the largest firms already enjoy extends beyond the monopolies or oligopolies that benefit many of them. They are also bolstering their financials and investing in the future in such a way that they are leaving their smaller brethren in the dust, rendering their lead invulnerable.

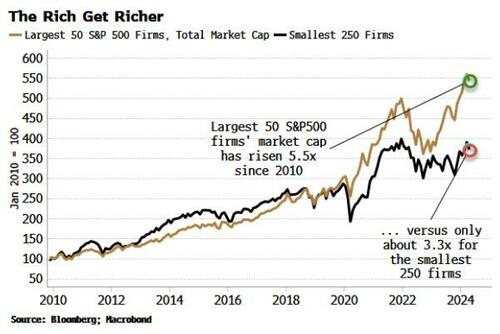

Large-cap indexes in the US have never been so concentrated, with the Magnificent Seven accounting for 27% of the S&P 500’s market cap. The outperformance really began to take off in the pandemic. Expanding to the largest 50 stocks in the S&P, we can see these began to significantly outpace the index’s smallest 250 members after 2020.

What lies behind this dominance? There are at least five reasons:

-

Massive loosening of monetary policy in the pandemic

-

The US running its largest ever pro-cyclical deficit

-

Tech firms benefiting from mass working-from-home during Covid

-

Companies taking advantage of the pandemic disruptions to raise margins by almost more than they ever have before – with the largest firms taking advantage of monopolies to raise prices the most

-

The AI boom kickstarted by ChatGPT

These advantages are allowing the largest firms to move into an unbeatable position, condemning the smallest ones to playing permanent second fiddle. Such a set-up means the bull market is fated to be mild compared to historical bull runs, as well as being less robust.

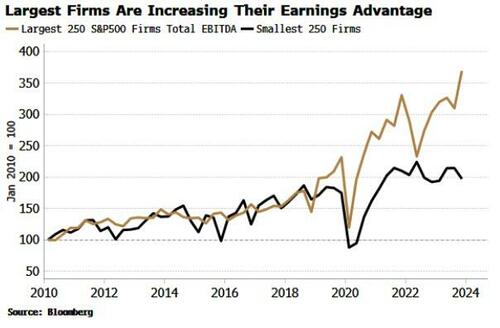

Market concentration can also be seen in earnings, with the largest 50 firms accounting for 35% of the S&P’s total Ebitda. An acceleration in earnings at the largest firms since the pandemic is fortifying that effect. The top 50’s Ebitda has risen over 3.5x since 2020, while it has only doubled for the smallest 250 companies in the S&P.

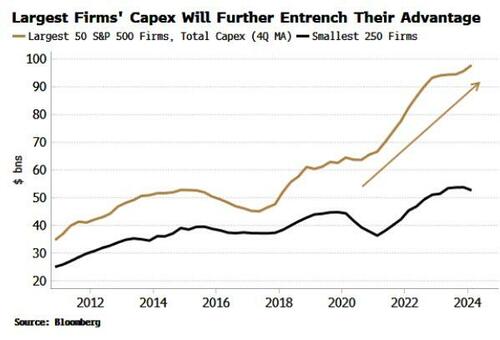

Those earnings are further ingraining big firms’ advantage. They are now outspending their smaller cousins on future investment on an epic scale. Tech firms are ploughing money into GPU chips, data centers and energy production in a way that makes it increasingly impossible for others to ever catch up – not only in technology, but across the economy as AI gnaws away more and more at the need for many jobs.

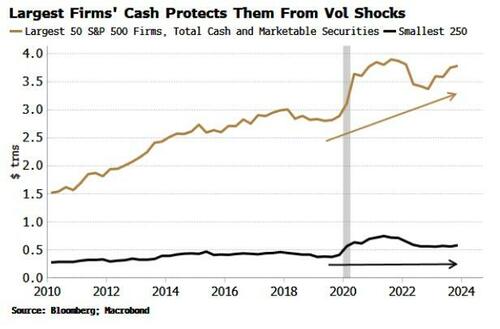

The largest firms are also bolstering their cash positions. While smaller companies’ cash and marketable securities is up only marginally since the pandemic, the pile at large firms is going from strength to strength and is on a strong upward trend. The biggest 50 companies in the S&P hold 53% of the index’s total corporate cash, compared to only 8% for the smallest 250.

Having cash is essentially being long volatility. If anything unexpected happens, you are in a better position to deal with it. A financial shock causes margins to rise? That cash is there to cover it. A rival goes bust? The cash can be used to acquire it on the cheap. Smaller firms are increasingly short volatility and are vulnerable to or are unable to capitalize from unexpected shocks.

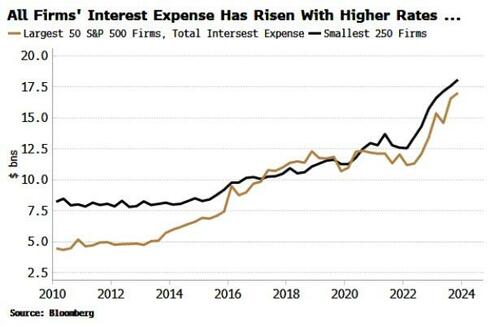

This cycle has been dominated by rising rates, so it’s no surprise interest expenses have increased across the board. The largest and the smallest firms have seen their quarterly interest costs climbing by about $7-8 billion since the pandemic.

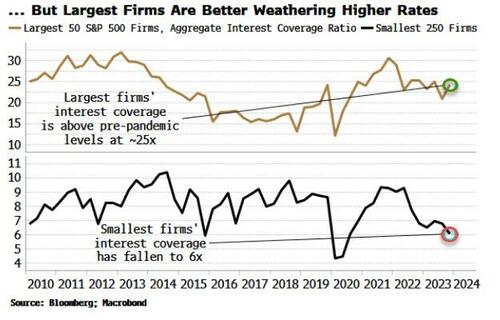

Yet once again, the largest firms come out on top. If we look at interest coverage, i.e. the ratio of Ebit to interest expense, the biggest companies’ coverage has been pretty stable, while the ratio for the smallest has been falling. In level terms, the difference is even more stark, with the biggest companies’ earnings covering their interest 25 times, versus only six times for their smaller counterparts. Even taking into account the extra interest received by corporates, the largest companies still come out on top.

Furthermore, both small and large firms have taken on more debt in recent years, but bigger companies are less vulnerable to debt downgrades as their cash position has risen even more relatively.

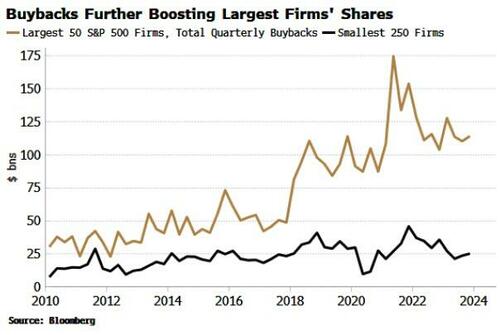

If all that is not enough to make the largest companies’ shares more attractive, they are also diverting more of their accelerating earnings to buying back their stock, mechanically helping to boost their price through reducing the share count. Smaller companies have not had the wherewithal to match them, even though in the years before the pandemic total buybacks were similar for small and large firms alike.

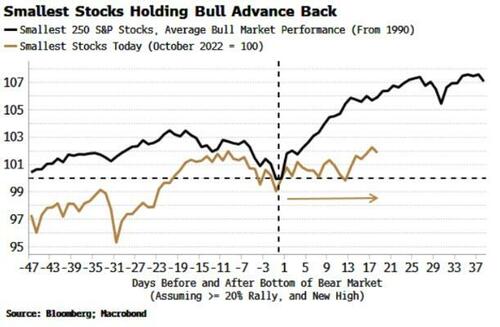

Like a camel train in the desert, smaller firms are at the back and falling further behind. This has implications for the bull market. The current one is mild compared to previous episodes, consistently lagging the average bull market over the last 35 years.

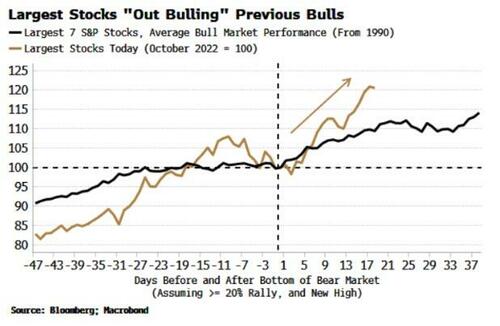

But a look under the hood shows why. The biggest stocks are now cleanly outperforming the average bull advance.

However, the smallest S&P stocks are heavily lagging behind their average bull performance.

Without any significant change, the bull market is likely to continue to pale next to the more virile examples in recent decades.

That’s not to say the largest stocks are immune to a correction or periods of underperformance.

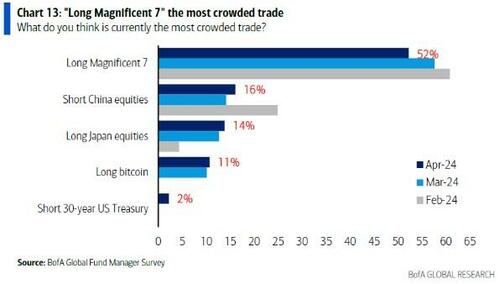

It certainly doesn’t help that they are viewed as the most crowded and consensus trades among US fund managers (according to BofA’s Global Fund Manager Survey).

Source: BofA

But it’s difficult to see — other than through their own unforced errors, or a complete reappraisal in attitudes to the near-term capabilities of AI and other new tech — how small companies can catch up on their larger rivals. Big is beautiful — and most probably now unassailable.

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

The largest firms in the US are unsurpassably pulling ahead of their smaller rivals by earning more, investing more, holding more cash and buying back more of their stock.

The bull market is thus likely to remain historically lackluster and less robust as smaller companies continue to lag their bigger counterparts.

They say the rich get richer, and nowhere is that more true than for the most-valuable firms in the US. The “Magnificent Seven” is by now a well-worn moniker for a septet of some of the biggest companies in the world, such as Nvidia, Apple and Amazon.

Yet the widening leadership that the largest firms already enjoy extends beyond the monopolies or oligopolies that benefit many of them. They are also bolstering their financials and investing in the future in such a way that they are leaving their smaller brethren in the dust, rendering their lead invulnerable.

Large-cap indexes in the US have never been so concentrated, with the Magnificent Seven accounting for 27% of the S&P 500’s market cap. The outperformance really began to take off in the pandemic. Expanding to the largest 50 stocks in the S&P, we can see these began to significantly outpace the index’s smallest 250 members after 2020.

What lies behind this dominance? There are at least five reasons:

-

Massive loosening of monetary policy in the pandemic

-

The US running its largest ever pro-cyclical deficit

-

Tech firms benefiting from mass working-from-home during Covid

-

Companies taking advantage of the pandemic disruptions to raise margins by almost more than they ever have before – with the largest firms taking advantage of monopolies to raise prices the most

-

The AI boom kickstarted by ChatGPT

These advantages are allowing the largest firms to move into an unbeatable position, condemning the smallest ones to playing permanent second fiddle. Such a set-up means the bull market is fated to be mild compared to historical bull runs, as well as being less robust.

Market concentration can also be seen in earnings, with the largest 50 firms accounting for 35% of the S&P’s total Ebitda. An acceleration in earnings at the largest firms since the pandemic is fortifying that effect. The top 50’s Ebitda has risen over 3.5x since 2020, while it has only doubled for the smallest 250 companies in the S&P.

Those earnings are further ingraining big firms’ advantage. They are now outspending their smaller cousins on future investment on an epic scale. Tech firms are ploughing money into GPU chips, data centers and energy production in a way that makes it increasingly impossible for others to ever catch up – not only in technology, but across the economy as AI gnaws away more and more at the need for many jobs.

The largest firms are also bolstering their cash positions. While smaller companies’ cash and marketable securities is up only marginally since the pandemic, the pile at large firms is going from strength to strength and is on a strong upward trend. The biggest 50 companies in the S&P hold 53% of the index’s total corporate cash, compared to only 8% for the smallest 250.

Having cash is essentially being long volatility. If anything unexpected happens, you are in a better position to deal with it. A financial shock causes margins to rise? That cash is there to cover it. A rival goes bust? The cash can be used to acquire it on the cheap. Smaller firms are increasingly short volatility and are vulnerable to or are unable to capitalize from unexpected shocks.

This cycle has been dominated by rising rates, so it’s no surprise interest expenses have increased across the board. The largest and the smallest firms have seen their quarterly interest costs climbing by about $7-8 billion since the pandemic.

Yet once again, the largest firms come out on top. If we look at interest coverage, i.e. the ratio of Ebit to interest expense, the biggest companies’ coverage has been pretty stable, while the ratio for the smallest has been falling. In level terms, the difference is even more stark, with the biggest companies’ earnings covering their interest 25 times, versus only six times for their smaller counterparts. Even taking into account the extra interest received by corporates, the largest companies still come out on top.

Furthermore, both small and large firms have taken on more debt in recent years, but bigger companies are less vulnerable to debt downgrades as their cash position has risen even more relatively.

If all that is not enough to make the largest companies’ shares more attractive, they are also diverting more of their accelerating earnings to buying back their stock, mechanically helping to boost their price through reducing the share count. Smaller companies have not had the wherewithal to match them, even though in the years before the pandemic total buybacks were similar for small and large firms alike.

Like a camel train in the desert, smaller firms are at the back and falling further behind. This has implications for the bull market. The current one is mild compared to previous episodes, consistently lagging the average bull market over the last 35 years.

But a look under the hood shows why. The biggest stocks are now cleanly outperforming the average bull advance.

However, the smallest S&P stocks are heavily lagging behind their average bull performance.

Without any significant change, the bull market is likely to continue to pale next to the more virile examples in recent decades.

That’s not to say the largest stocks are immune to a correction or periods of underperformance.

It certainly doesn’t help that they are viewed as the most crowded and consensus trades among US fund managers (according to BofA’s Global Fund Manager Survey).

Source: BofA

But it’s difficult to see — other than through their own unforced errors, or a complete reappraisal in attitudes to the near-term capabilities of AI and other new tech — how small companies can catch up on their larger rivals. Big is beautiful — and most probably now unassailable.

Loading…