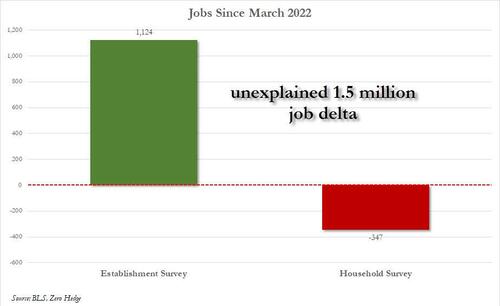

Yesterday we explained why contrary to the widespread praise for the Friday payrolls report, a closer look at the data below the surface revealed a far weaker labor market than the one trumpeted by the Biden administration, not least of all because while the Establishment Survey hinted a continued strong jobs growth (with +372K payrolls in June, over a 100K more than the 268K median estimate), the Household Survey contrasted with a far weaker picture, indicating 315K jobs lost, and zero actual growth in employment since March...

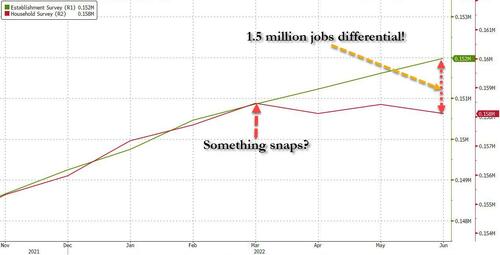

... a bizarre differential of nearly 1.5 million jobs between the two surveys since March...

... and one which is increasingly manifesting itself in loss of full and part-time jobs at the expense of multiple jobholders (see "Something Snaps In The US Labor Market: Full, Part-Time Workers Plunge As Multiple Jobholders Soar" for details.)

Still, while one can debate the nuances in the data, pro-admin economists and permabulls will argue that whether the 372K print is up or down by a few hundred thousand, is irrelevant: after all, there is no way the US economy can slide into a recession with such (still) solid labor market gains, right? And the latest jobs report certainly does not change anything for the Fed: after all, there is neither enough job weakness nor wage deceleration for Powell to shift course.

In other words, we can't have a recession with unemployment so low and payrolls so strong.

But is that true? Well, as Piper Sandler's Nancy Lazar counters, neither is a leading indicator - they're at best coincident - and unemployment always bottoms out just before recessions (especially since the continued slowdown in wage growth indicates the return of lower-paid jobs, and raises the odds we do not have a wage-price spiral but instead see price-slowdown).

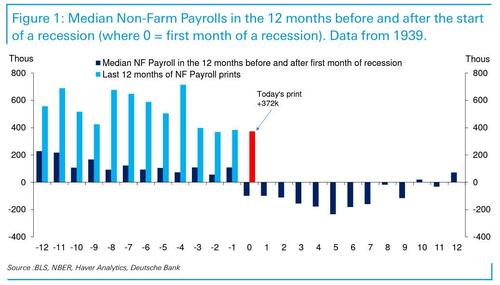

Overnight, DB's Jim Reid also chimed in, echoing our caution and writing that "we have to be careful of today’s big +372k payroll print as the figure can seem a bit of a random number generator" yet even so, he notes that through history a recession usually has a negative print in the first month of it being declared, which then carries on for the vast majority of the subsequent year.

While this clearly hasn't happened yet, there are two key caveats: as Reid explains, the problem for forecasters and markets is that

- the recession is declared retrospectively, so it’s usually too late to wait for official confirmation, and by the time the negative prints arrive it will be time to start forecasting the end of the recession, and...

- history suggests little evidence of a gradual decline in payrolls in the months leading up to recession.

Indeed, it may come as a shock to macrotourists who claim we need to see a gradual decline into the red for a recession to emerge, but as Reid's chart of the day shows, the median payroll 10 months before a recession is the same as the final month before a recession with little sign of a trend in the months between!

In other words, confirming what Piper Sanlder said above, payrolls in themselves give no advance warning, and if anything give false positives because while they remain in the green, the economy has already contracted.

Still, as Reid concludes, it is striking how strong job growth has been in recent months as we recover from the pandemic. This will likely be under more pressure soon as the lagged effect of inflation and the Fed hiking cycle kick in, but for now it remains historically very strong.

As such, the timing of the eventual recession (outside of the technical definition) will be closely tied to when payrolls go negative and appear likely to stay there. And while we are not there yet, the DB strategist warns that "it looks inevitable that we will be, over the next 12 months."

Yesterday we explained why contrary to the widespread praise for the Friday payrolls report, a closer look at the data below the surface revealed a far weaker labor market than the one trumpeted by the Biden administration, not least of all because while the Establishment Survey hinted a continued strong jobs growth (with +372K payrolls in June, over a 100K more than the 268K median estimate), the Household Survey contrasted with a far weaker picture, indicating 315K jobs lost, and zero actual growth in employment since March…

… a bizarre differential of nearly 1.5 million jobs between the two surveys since March…

… and one which is increasingly manifesting itself in loss of full and part-time jobs at the expense of multiple jobholders (see “Something Snaps In The US Labor Market: Full, Part-Time Workers Plunge As Multiple Jobholders Soar” for details.)

Still, while one can debate the nuances in the data, pro-admin economists and permabulls will argue that whether the 372K print is up or down by a few hundred thousand, is irrelevant: after all, there is no way the US economy can slide into a recession with such (still) solid labor market gains, right? And the latest jobs report certainly does not change anything for the Fed: after all, there is neither enough job weakness nor wage deceleration for Powell to shift course.

In other words, we can’t have a recession with unemployment so low and payrolls so strong.

But is that true? Well, as Piper Sandler’s Nancy Lazar counters, neither is a leading indicator – they’re at best coincident – and unemployment always bottoms out just before recessions (especially since the continued slowdown in wage growth indicates the return of lower-paid jobs, and raises the odds we do not have a wage-price spiral but instead see price-slowdown).

Overnight, DB’s Jim Reid also chimed in, echoing our caution and writing that “we have to be careful of today’s big +372k payroll print as the figure can seem a bit of a random number generator” yet even so, he notes that through history a recession usually has a negative print in the first month of it being declared, which then carries on for the vast majority of the subsequent year.

While this clearly hasn’t happened yet, there are two key caveats: as Reid explains, the problem for forecasters and markets is that

- the recession is declared retrospectively, so it’s usually too late to wait for official confirmation, and by the time the negative prints arrive it will be time to start forecasting the end of the recession, and…

- history suggests little evidence of a gradual decline in payrolls in the months leading up to recession.

Indeed, it may come as a shock to macrotourists who claim we need to see a gradual decline into the red for a recession to emerge, but as Reid’s chart of the day shows, the median payroll 10 months before a recession is the same as the final month before a recession with little sign of a trend in the months between!

In other words, confirming what Piper Sanlder said above, payrolls in themselves give no advance warning, and if anything give false positives because while they remain in the green, the economy has already contracted.

Still, as Reid concludes, it is striking how strong job growth has been in recent months as we recover from the pandemic. This will likely be under more pressure soon as the lagged effect of inflation and the Fed hiking cycle kick in, but for now it remains historically very strong.

As such, the timing of the eventual recession (outside of the technical definition) will be closely tied to when payrolls go negative and appear likely to stay there. And while we are not there yet, the DB strategist warns that “it looks inevitable that we will be, over the next 12 months.”