By Ven Ram, Bloomberg Markets Live commentator and reporter

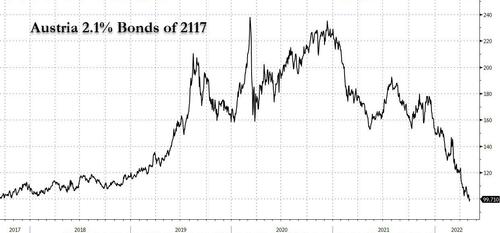

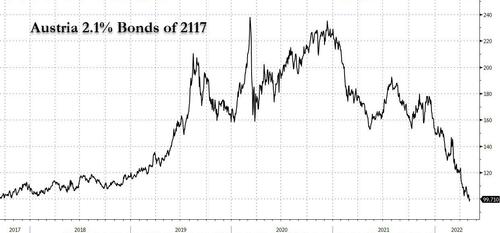

Last week, a bond Austria first issued in 2017 came back full circle.

The event went almost unnoticed, but the symbolism of the move was historic.

On Friday, the bond closed below par for the first time since it was issued. As bonds go, the issuance was unique. What was special about the bond was its tenor: it wasn’t due to be redeemed for a hundred years. And it was sold at a paltry yield of around 2.10%. That must have been the moment of ultimate duration risk (around then, 10-year German bonds offered just 0.36%, and Europe was steeped in negative rates). From then and until last week, the bond traded as high as 240 cents on par, but never below where it was issued.

Now, of course, the narrative has changed completely.

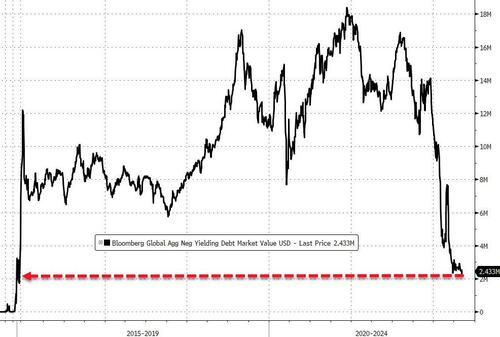

Negative-yielding bonds are fast receding like a humongous wave from a beach, and for the better.

When then-European Central Bank President Mario Draghi took benchmark rates negative, the idea was that it would kindle inflation.

For years, rates kept going deeper and deeper into negative territory, but there was hardly any inflation to show for the efforts - what inflation we have now has, of course, followed the pandemic and the war. Proponents of negative rates would like to claim that the situation would have been much worse had it not been for their efforts, but that is a tall claim with little empirical proof. Which is perhaps why the Fed steered away from going below zero in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic.

The ECB under Christine Lagarde has shown that it is keen to get off negative rates, and if the monetary authority does manage to convert its intent into action, the curtains may come down on an era when pension funds and insurers pretty much had no choice but to take on too much duration risk for too little by way of compensation.

By Ven Ram, Bloomberg Markets Live commentator and reporter

Last week, a bond Austria first issued in 2017 came back full circle.

The event went almost unnoticed, but the symbolism of the move was historic.

On Friday, the bond closed below par for the first time since it was issued. As bonds go, the issuance was unique. What was special about the bond was its tenor: it wasn’t due to be redeemed for a hundred years. And it was sold at a paltry yield of around 2.10%. That must have been the moment of ultimate duration risk (around then, 10-year German bonds offered just 0.36%, and Europe was steeped in negative rates). From then and until last week, the bond traded as high as 240 cents on par, but never below where it was issued.

Now, of course, the narrative has changed completely.

Negative-yielding bonds are fast receding like a humongous wave from a beach, and for the better.

When then-European Central Bank President Mario Draghi took benchmark rates negative, the idea was that it would kindle inflation.

For years, rates kept going deeper and deeper into negative territory, but there was hardly any inflation to show for the efforts – what inflation we have now has, of course, followed the pandemic and the war. Proponents of negative rates would like to claim that the situation would have been much worse had it not been for their efforts, but that is a tall claim with little empirical proof. Which is perhaps why the Fed steered away from going below zero in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic.

The ECB under Christine Lagarde has shown that it is keen to get off negative rates, and if the monetary authority does manage to convert its intent into action, the curtains may come down on an era when pension funds and insurers pretty much had no choice but to take on too much duration risk for too little by way of compensation.