Authored by Allen Stein via The Epoch Times,

Jeff Worsham is a realist regarding the weather because he believes what he sees.

That the regional drought is a bad one, getting worse, is beyond dispute. The Mississippi River is at the lowest it’s been in decades, he said.

Worse, the barges are backing up because of it, running aground, and wreaking havoc on the regional supply chain.

“There’s no relief in sight as far as rainfall,” said Worsham, port manager of Poinsett Rice & Grain’s loading facility in Osceola, Arkansas.

When will it rain next?

Worsham said, “Who knows?”

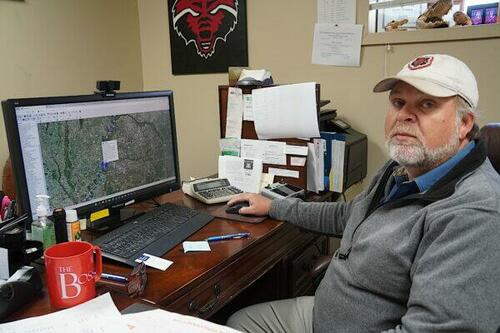

Jeff Worsham, port manager of Poinsett Rice & Grain in Osceola, Ark., said the Mississippi River is at the lowest it’s been in decades due to an ongoing drought wreaking havoc with commercial barge lines. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

Loaded at about 65 percent capacity with soybeans to reduce weight, the barges at the Osceola facility have been “dead in the water” for days in a jagged queue, blocked by a single barge that became stuck in the shallow mouth of the port.

Unprecedented Times

“I’ve never seen it this bad,” said Worsham, who’s been with the company for over 20 years. “We had water [levels] close to this in 2012. But it was August, and it wasn’t the harvesting season. It wasn’t a big deal for us.”

At the height of the corn and soybean harvest, and with tons of products waiting to be shipped, Worsham remains optimistic.

“A lot of the soybeans have been stored on the barges. We’ll be down a little bit on volume and stretched out. We’ll be able to get the bushels [out]. It’s just going to take longer,” he told The Epoch Times.

Barge loader Raul Rivas walks to the loading station at Poinsett Rice Grain on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

Worsham said a tow boat would eventually drag the stuck barge to deeper water and free up the other barges. He said until then, nothing can get in or out of the port—and then the phone rang.

It was Worsham’s boss asking for an update.

“It’s more than hard,” Worsham told his supervisor. “They would get them [out] if they could … I don’t know what else to do.”

The situation is no less challenging with other competing barge lines, Worsham said.

In recent weeks, hundreds of barges have become stalled in the receding Mississippi, caught in the lower depths. In early October, some 2,000 barges reportedly clogged the channels in long pileups along the river south of Memphis.

The barges need around a nine-foot depth to navigate. The problem is that the water levels have fallen so low in many places even the tugboats are getting stuck.

Barges sit in the port facility at Poinsett Rice & Grain in Osceola, Ark., on Oct. 20, 2022. Behind the barges, the river tributary’s water line has been receding for months in the continuing drought. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

Near the Gulf of Mexico, the ocean has begun seeping into the weakening river, threatening the water supply. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is working to build a temporary levee to fend off the ocean’s slow advance north.

Situation ‘Grave’

As the nation’s second-largest river, the Mississippi stretches 2,340 miles from its source at Lake Itasca in northwestern Minnesota to the Gulf. The river provides easy access for midwestern farmers looking to ship their products cheaply and efficiently.

Commercial barges each year account for about 418 million tons of goods moved between U.S. ports along the Mississippi River system. Nationally, it’s around 700 million tons.

But as water levels continue to fall, it allows less room for the barges to navigate and more opportunities to become stuck, said Ben Lerner, vice president of public affairs for the American Waterways Operators, a national trade association.

Lerner said the Mississippi River at a historically low level presents a significant challenge for the nation’s supply chain.

“In some spots in the river, it is at its lowest level since 1988, so it’s a real challenge for the supply chain and our industry,” Lerner told The Epoch Times.

Barges laden with agricultural products now have longer waiting times to deliver their cargos while in transit, causing back-ups along the river.

Lerner said a standard barge has 16 rail cars or 70 semi trucks carrying capacity, but it’s cheaper and more efficient.

“The bottom line is the American barge industry is a major component of the global and American supply chain. If we can’t move cargo on the Mississippi efficiently, that ultimately has far-reaching economic implications,” he said.

“I don’t want to understate the gravity of the situation we’re dealing with—the tremendous strain on the supply chain.”

Barge loader Raul Rivas (R), deckhand Clifton Brown (L), and other workers at Poinsett Rice & Grain in Osceola, Ark., walk to the loading docks on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

At its widest point, the Mississippi River is over seven miles wide, allowing for as many as 42 lashed barges to operate, pushed by a single tow boat.

“We’ve got a river now that’s shallower and narrower than it’s ever been,” Lerner told The Epoch Times.

Many commercial barge lines have reduced loads by as much as 50 percent to compensate for the shallower water. Other barge lines have switched to shipping via the more costly and less efficient rail and trucking systems.

“The more shippers switch to rail or truck to move their cargo, the more congested our railways and highways ultimately become,” Lerner said.

It also translates into higher costs for the nation’s agricultural producers, 92 percent of whose output travels through the Mississippi River Basin.

About 60 percent of grain and 54 percent of soybeans for U.S. export rely on barges for delivery to foreign and domestic markets, according to FreightWaves.

The market research site ReportLinker.com projected that the U.S. barge transportation market should grow from $25.17 billion in 2021 to around $39.9 billion by 2028 due to increased demand, infrastructure, and investment.

Poinsett Rice & Grain deck hand Clifton Brown points to where the water level used to be at the loading port near the Mississippi River on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

“The system needs water,” said Lerner, confident that the commercial barge industry is resilient and accustomed to operating in a crisis.

‘Game Time’ For Farmers

“It’s a significant challenge for U.S. agriculture and farmers to be successful and profitable,” noted Mike Steenhoek, executive director of the Soy Transportation Coalition.

The organization comprises 13 state soybean boards, including the American Soybean Association and the United Soybean Board, encompassing 85 percent of soybean production.

Steenhoek said while farmers are geographically distant from coastal ports, they enjoy easy access to inland waterways like the Mississippi, Ohio, and Illinois rivers.

“It’s game time for agriculture,” Steenhoek said. “When the system operates as normal, there’s no more effective way of moving commodities long distances in an economical manner” than commercial barges.

“When the system goes awry, it poses a significant hardship.”

The problem going into 2022 has been the lack of rain and snowmelt to replenish inland rivers to allow the ground to become saturated ahead of the spring planting season.

A large pile of beans lies under a tarp at Consolidated Grain & Barge in West Memphis, Ark., as seen from the highway on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

While crops this year have benefited from the available moisture, very little has made its way into the water system, contributing to lower river levels.

“When you have a [barge] grounding, it’s a major effort to alleviate,” Steenhoek said. “It shuts down the river. So you have to resort to putting less freight per barge.”

Steenhoek said in the case of soybeans, for every 12 inches of lost channel depth, a standard barge must shed 5,000 bushels—about 136 tons—to stay afloat. He said it means that fewer barges can operate in tandem, resulting in the industry-imposed maximum of 25 lashed barges per shipment.

“You don’t have your optimal route available to you. It still will find a way—maybe not as much as normal—not as efficiently as normal,” Steenhoek said. “Whenever you have a disruption like this, those costs get passed on. It adds a lot of costs [and] the farmer will bear a lot of that.

“Some of it’s going to be borne by the shipper. It adds insult to injury when you’ve got challenges with our inland waterway system.”

Other barge lines, such as Consolidated Grain and Barge Co. in West Memphis, have begun storing beans in large outdoor piles under tarps in the wake of the barge crisis.

Steenhoek compared switching transportation modes from barge to rail and truck to a garden hose attached to a fire hydrant, where “you’ve got lots of [product] volume” and less efficient ways to move it.

A towboat sits in its dock along the Mississippi River in Memphis, Tenn., on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

“When you’re in that scenario, it’s not efficient, and it’s not as cost-effective. There are consequences,” he said. “What’s particularly inopportune right now and consequential is how comprehensive it is—not just one part of our nation. It’s the whole [transportation] system” under stress.

Worse Before It Gets Better

Poinsett Rice & Grain operates with a fleet of 100 barges, each of which carries around 85,000 bushels of rice, soybeans, or corn to ports along the river. Those volumes are about 35,000 bushels less in the drought to reduce weight and increase floating capacity.

“Hopefully, we will be able to continue operations. It’s gotten a lot worse [but] we’re still loading,” Worsham said.

The company, which ships around five or six million bushels per year, had expected to ship eight million bushels this year, given the robust harvest.

Worsham said that number is down to around three million bushels.

“We’ll probably match last year’s volume” of around four million bushels.”

Poinsett Rice & Grain barge loader Raul Rivas points to the long line of barges awaiting delivery of soybeans on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

Barge loader Raul Rivas said the barge logjam at the Poinsett facility is a logistics headache.

“We can’t load that many barges right now. The traffic right here can’t get in and out. Right now, this will be our last barge for a while,” Rivas said.

Typically, Rivas’ crew will load three barges daily with soybeans, rice, or corn from loading towers.

“There isn’t much we can do. Everything we’ve got is overstocked or on the ground. We got one [barge] stuck last night. We had to get to the tugboat at least until it broke free. Then we finished loading [the barge],” Rivas said.

“Supposedly, when it gets down to a negative 12 [feet level], that’s when they’re supposed to shut the barges and boats down.”

A grain loader operator awaits instructions at Poinsett Rice & Grain in Osceola, Ark., on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

Poinsett deck hand Clifton Brown said that dock workers have been “running into a lot of problems” with the low water levels, now going on two months.

“That’s about the worst of it—[barges] getting stuck. It’s pretty rough on us just loading barges right now. See that barge over there, stuck on the bank, on the corner?”

Brown pointed toward the far end of the port at the former water line where that “used to be to those trees.”

In the current drought, Brown also remains positive, saying it’s only a matter of time before the Mississippi is back up and running as the water level fluctuates.

“We’ll be down for another week or so until the river comes back up. Everything is good.”

Authored by Allen Stein via The Epoch Times,

Jeff Worsham is a realist regarding the weather because he believes what he sees.

That the regional drought is a bad one, getting worse, is beyond dispute. The Mississippi River is at the lowest it’s been in decades, he said.

Worse, the barges are backing up because of it, running aground, and wreaking havoc on the regional supply chain.

“There’s no relief in sight as far as rainfall,” said Worsham, port manager of Poinsett Rice & Grain’s loading facility in Osceola, Arkansas.

When will it rain next?

Worsham said, “Who knows?”

Jeff Worsham, port manager of Poinsett Rice & Grain in Osceola, Ark., said the Mississippi River is at the lowest it’s been in decades due to an ongoing drought wreaking havoc with commercial barge lines. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

Loaded at about 65 percent capacity with soybeans to reduce weight, the barges at the Osceola facility have been “dead in the water” for days in a jagged queue, blocked by a single barge that became stuck in the shallow mouth of the port.

Unprecedented Times

“I’ve never seen it this bad,” said Worsham, who’s been with the company for over 20 years. “We had water [levels] close to this in 2012. But it was August, and it wasn’t the harvesting season. It wasn’t a big deal for us.”

At the height of the corn and soybean harvest, and with tons of products waiting to be shipped, Worsham remains optimistic.

“A lot of the soybeans have been stored on the barges. We’ll be down a little bit on volume and stretched out. We’ll be able to get the bushels [out]. It’s just going to take longer,” he told The Epoch Times.

Barge loader Raul Rivas walks to the loading station at Poinsett Rice Grain on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

Worsham said a tow boat would eventually drag the stuck barge to deeper water and free up the other barges. He said until then, nothing can get in or out of the port—and then the phone rang.

It was Worsham’s boss asking for an update.

“It’s more than hard,” Worsham told his supervisor. “They would get them [out] if they could … I don’t know what else to do.”

The situation is no less challenging with other competing barge lines, Worsham said.

In recent weeks, hundreds of barges have become stalled in the receding Mississippi, caught in the lower depths. In early October, some 2,000 barges reportedly clogged the channels in long pileups along the river south of Memphis.

The barges need around a nine-foot depth to navigate. The problem is that the water levels have fallen so low in many places even the tugboats are getting stuck.

Barges sit in the port facility at Poinsett Rice & Grain in Osceola, Ark., on Oct. 20, 2022. Behind the barges, the river tributary’s water line has been receding for months in the continuing drought. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

Near the Gulf of Mexico, the ocean has begun seeping into the weakening river, threatening the water supply. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is working to build a temporary levee to fend off the ocean’s slow advance north.

Situation ‘Grave’

As the nation’s second-largest river, the Mississippi stretches 2,340 miles from its source at Lake Itasca in northwestern Minnesota to the Gulf. The river provides easy access for midwestern farmers looking to ship their products cheaply and efficiently.

Commercial barges each year account for about 418 million tons of goods moved between U.S. ports along the Mississippi River system. Nationally, it’s around 700 million tons.

But as water levels continue to fall, it allows less room for the barges to navigate and more opportunities to become stuck, said Ben Lerner, vice president of public affairs for the American Waterways Operators, a national trade association.

Lerner said the Mississippi River at a historically low level presents a significant challenge for the nation’s supply chain.

“In some spots in the river, it is at its lowest level since 1988, so it’s a real challenge for the supply chain and our industry,” Lerner told The Epoch Times.

Barges laden with agricultural products now have longer waiting times to deliver their cargos while in transit, causing back-ups along the river.

Lerner said a standard barge has 16 rail cars or 70 semi trucks carrying capacity, but it’s cheaper and more efficient.

“The bottom line is the American barge industry is a major component of the global and American supply chain. If we can’t move cargo on the Mississippi efficiently, that ultimately has far-reaching economic implications,” he said.

“I don’t want to understate the gravity of the situation we’re dealing with—the tremendous strain on the supply chain.”

Barge loader Raul Rivas (R), deckhand Clifton Brown (L), and other workers at Poinsett Rice & Grain in Osceola, Ark., walk to the loading docks on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

At its widest point, the Mississippi River is over seven miles wide, allowing for as many as 42 lashed barges to operate, pushed by a single tow boat.

“We’ve got a river now that’s shallower and narrower than it’s ever been,” Lerner told The Epoch Times.

Many commercial barge lines have reduced loads by as much as 50 percent to compensate for the shallower water. Other barge lines have switched to shipping via the more costly and less efficient rail and trucking systems.

“The more shippers switch to rail or truck to move their cargo, the more congested our railways and highways ultimately become,” Lerner said.

It also translates into higher costs for the nation’s agricultural producers, 92 percent of whose output travels through the Mississippi River Basin.

About 60 percent of grain and 54 percent of soybeans for U.S. export rely on barges for delivery to foreign and domestic markets, according to FreightWaves.

The market research site ReportLinker.com projected that the U.S. barge transportation market should grow from $25.17 billion in 2021 to around $39.9 billion by 2028 due to increased demand, infrastructure, and investment.

Poinsett Rice & Grain deck hand Clifton Brown points to where the water level used to be at the loading port near the Mississippi River on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

“The system needs water,” said Lerner, confident that the commercial barge industry is resilient and accustomed to operating in a crisis.

‘Game Time’ For Farmers

“It’s a significant challenge for U.S. agriculture and farmers to be successful and profitable,” noted Mike Steenhoek, executive director of the Soy Transportation Coalition.

The organization comprises 13 state soybean boards, including the American Soybean Association and the United Soybean Board, encompassing 85 percent of soybean production.

Steenhoek said while farmers are geographically distant from coastal ports, they enjoy easy access to inland waterways like the Mississippi, Ohio, and Illinois rivers.

“It’s game time for agriculture,” Steenhoek said. “When the system operates as normal, there’s no more effective way of moving commodities long distances in an economical manner” than commercial barges.

“When the system goes awry, it poses a significant hardship.”

The problem going into 2022 has been the lack of rain and snowmelt to replenish inland rivers to allow the ground to become saturated ahead of the spring planting season.

A large pile of beans lies under a tarp at Consolidated Grain & Barge in West Memphis, Ark., as seen from the highway on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

While crops this year have benefited from the available moisture, very little has made its way into the water system, contributing to lower river levels.

“When you have a [barge] grounding, it’s a major effort to alleviate,” Steenhoek said. “It shuts down the river. So you have to resort to putting less freight per barge.”

Steenhoek said in the case of soybeans, for every 12 inches of lost channel depth, a standard barge must shed 5,000 bushels—about 136 tons—to stay afloat. He said it means that fewer barges can operate in tandem, resulting in the industry-imposed maximum of 25 lashed barges per shipment.

“You don’t have your optimal route available to you. It still will find a way—maybe not as much as normal—not as efficiently as normal,” Steenhoek said. “Whenever you have a disruption like this, those costs get passed on. It adds a lot of costs [and] the farmer will bear a lot of that.

“Some of it’s going to be borne by the shipper. It adds insult to injury when you’ve got challenges with our inland waterway system.”

Other barge lines, such as Consolidated Grain and Barge Co. in West Memphis, have begun storing beans in large outdoor piles under tarps in the wake of the barge crisis.

Steenhoek compared switching transportation modes from barge to rail and truck to a garden hose attached to a fire hydrant, where “you’ve got lots of [product] volume” and less efficient ways to move it.

A towboat sits in its dock along the Mississippi River in Memphis, Tenn., on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

“When you’re in that scenario, it’s not efficient, and it’s not as cost-effective. There are consequences,” he said. “What’s particularly inopportune right now and consequential is how comprehensive it is—not just one part of our nation. It’s the whole [transportation] system” under stress.

Worse Before It Gets Better

Poinsett Rice & Grain operates with a fleet of 100 barges, each of which carries around 85,000 bushels of rice, soybeans, or corn to ports along the river. Those volumes are about 35,000 bushels less in the drought to reduce weight and increase floating capacity.

“Hopefully, we will be able to continue operations. It’s gotten a lot worse [but] we’re still loading,” Worsham said.

The company, which ships around five or six million bushels per year, had expected to ship eight million bushels this year, given the robust harvest.

Worsham said that number is down to around three million bushels.

“We’ll probably match last year’s volume” of around four million bushels.”

Poinsett Rice & Grain barge loader Raul Rivas points to the long line of barges awaiting delivery of soybeans on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

Barge loader Raul Rivas said the barge logjam at the Poinsett facility is a logistics headache.

“We can’t load that many barges right now. The traffic right here can’t get in and out. Right now, this will be our last barge for a while,” Rivas said.

Typically, Rivas’ crew will load three barges daily with soybeans, rice, or corn from loading towers.

“There isn’t much we can do. Everything we’ve got is overstocked or on the ground. We got one [barge] stuck last night. We had to get to the tugboat at least until it broke free. Then we finished loading [the barge],” Rivas said.

“Supposedly, when it gets down to a negative 12 [feet level], that’s when they’re supposed to shut the barges and boats down.”

A grain loader operator awaits instructions at Poinsett Rice & Grain in Osceola, Ark., on Oct. 20, 2022. (Allan Stein/The Epoch Times)

Poinsett deck hand Clifton Brown said that dock workers have been “running into a lot of problems” with the low water levels, now going on two months.

“That’s about the worst of it—[barges] getting stuck. It’s pretty rough on us just loading barges right now. See that barge over there, stuck on the bank, on the corner?”

Brown pointed toward the far end of the port at the former water line where that “used to be to those trees.”

In the current drought, Brown also remains positive, saying it’s only a matter of time before the Mississippi is back up and running as the water level fluctuates.

“We’ll be down for another week or so until the river comes back up. Everything is good.”