It was exactly a year ago, when Deutsche Bank strategist Luke Templeman said that amid the panicked scramble by US wholesalers to stock up on scarce inventory as a result of snarled supply chains, it was only a matter of time before the US economy was roiled by a "bullwhip" (or whiplash) effect.

Some details for those unfamiliar with this concept: the bullwhip effect occurs when a drop in customer demand causes retailers to under stock. In turn, wholesalers respond to a lack of retail orders by understocking themselves. That then causes manufacturers to slow production. Eventually the reverse occurs. As customer demand comes back, retailers quickly order more goods, often too much, and wholesalers and factories are caught short. Shortages occur, prices increase. Eventually production ramps up at levels that are far beyond equilibrium levels and this cascades down the chain. These violent swings in availability of goods then continue back and forth until an equilibrium is eventually established.

Last May, the beginning of the bullwhip effect was seen in the way retailers and wholesalers managed their inventory levels since the outbreak of covid. Specifically, retailers kept a supply of inventory at a relatively constant level, above that of wholesalers. As covid hit, supply chains from Asia were cut which caused a fright amongst retailers in the West who immediately began to put in orders for more inventory. A whole lot more of it. Subsequent lockdowns saw demand plummet and inventories along with it. In both cases, the actions of wholesalers followed those of retailers by a month or so.

In the context of a starting bullwhip effect, Templeman's conclusion was accurate: "As inventory levels have fallen to multi-decade lows at retailers, there are likely many businesses that will not have enough inventory to satisfy customers as economies recover and pent-up demand is unleashed. This is particularly the case as retailers are far more reliant on just-in-time supply chains than they were in decades past."

Among other things, this is also why last May is when a historic bout of inflation was unleashed (one which not a single career economist or Fed official predicted correctly) as collapsing inventories and lack of restocking by jammed up supply chains meant that prices for goods would keep rising and rising and rising. And they did.

Of course, for much of the past year, the big story was the congestion at west coast ports due to both external (China covid breakouts, port closures, changing legislation) and internal factors (lack of port workers, downstream supply jams including trucking and trains, etc) but that has now changed and as the latest Supply Chain Congestion Monitor report from JPMorgan (available to pro subscribers in the usual place) shows, the number of ships at anchor and on approach to L.A. and Long Beach has collapsed since the January high mark, and is back to levels first seen at the start of the covid pandemic.

Why does this matter? Well, for a simple but critical reason: if one year ago we saw the hyperinflationary start of the bullwhip effect, we have entered the terminal phase of the "bullwhip effect", where plunging inventory-to-sales ratios reverse violently higher, where supply chains unclog suddenly and rapidly amid a sudden chill in the economy, and where prices for so-called "core" goods collapse almost overnight, even as non-core prices (food and energy) explode even higher.

This is how Freight Waves discussed this effect on Friday when commenting on the recent dire earnings (and outlook) from the largest US retailers such as Walmart and Target, which saw their prices crater as management warned that inflation is now crippling demand and snuffing profit margins:

"furniture, home furnishings and appliances, building materials and garden equipment, and a category known as “other general merchandise,” which includes Walmart and Target, among others, reported higher inventory-to-sales ratios, according to government data analyzed by Michigan State."

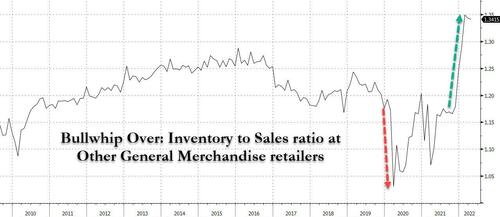

How much higher? A quick look at the latest data reveals the following stunning chart of the Inventory to Sales ratio at the Walmarts of the world at the highest level since just before the deflationary flashbang that was the Global Financial Crisis:

Think: widespread inventory liquidations.

As Freight Waves continues, "the change has happened fast, according to Jason Miller, logistics professor at MSU’s Eli Broad College of Business. As of November, inventory-to-sales ratios were at pre-COVID levels, Miller said. They have since exploded upward. Miller said he expects a “cooldown” in retailer order volumes, even if inflation-adjusted sales stay constant, as retailers look to reduce their existing stock."

And here is the punchline: Miller "also expects retailers to launch major discounting programs to expedite the inventory burn."

In short: we are about to see the mother of all liquidations as retailers scramble to unload inventory in a time off rampant demand destruction. The immediate result is the freight recession that was first (correctly) forecast by FreightWaves CEO Craig Fuller at the end of March and which is now coming true as the crashing stock price of countless trucker and other freight stocks has demonstrated. Some more on this:

high inventory levels are an expected occurrence and should be welcomed. In a Tuesday note, Amit Mehrotra, transport analyst at Deutsche Bank, said rising buffer stock is part of retailers’ desire to have goods available when consumers scan the shelves. Mehrotra added, however, that the data points translate into a likely slowdown in freight flows in the coming months and quarters.

He said that a recession is already priced into most transportation equities, noting that the shares of most trucking companies are higher over the past 30 days while the broader market is about 7% lower.

The latest data also confirms what FreightWaves' Fuller said in a subsequent post when he wondered if "Deflation Was Next" as "the Bullwhip was about do the Fed's job on inflation."

To be sure, not every product will see its price cut: commodities, whose bullwhip effect take much longer to manifest itself, usually lasting several years in either direction, are only just starting to see their price cycle higher. However, other products - like those carried by the Walmarts and Targets of the world - are about to see a deflationary plunge the likes of which we have not seen since the global financial crisis as retailers commence a voluntary destocking wave the likes of which have not been seen in over a decade.

It was exactly a year ago, when Deutsche Bank strategist Luke Templeman said that amid the panicked scramble by US wholesalers to stock up on scarce inventory as a result of snarled supply chains, it was only a matter of time before the US economy was roiled by a “bullwhip” (or whiplash) effect.

Some details for those unfamiliar with this concept: the bullwhip effect occurs when a drop in customer demand causes retailers to under stock. In turn, wholesalers respond to a lack of retail orders by understocking themselves. That then causes manufacturers to slow production. Eventually the reverse occurs. As customer demand comes back, retailers quickly order more goods, often too much, and wholesalers and factories are caught short. Shortages occur, prices increase. Eventually production ramps up at levels that are far beyond equilibrium levels and this cascades down the chain. These violent swings in availability of goods then continue back and forth until an equilibrium is eventually established.

Last May, the beginning of the bullwhip effect was seen in the way retailers and wholesalers managed their inventory levels since the outbreak of covid. Specifically, retailers kept a supply of inventory at a relatively constant level, above that of wholesalers. As covid hit, supply chains from Asia were cut which caused a fright amongst retailers in the West who immediately began to put in orders for more inventory. A whole lot more of it. Subsequent lockdowns saw demand plummet and inventories along with it. In both cases, the actions of wholesalers followed those of retailers by a month or so.

In the context of a starting bullwhip effect, Templeman’s conclusion was accurate: “As inventory levels have fallen to multi-decade lows at retailers, there are likely many businesses that will not have enough inventory to satisfy customers as economies recover and pent-up demand is unleashed. This is particularly the case as retailers are far more reliant on just-in-time supply chains than they were in decades past.”

Among other things, this is also why last May is when a historic bout of inflation was unleashed (one which not a single career economist or Fed official predicted correctly) as collapsing inventories and lack of restocking by jammed up supply chains meant that prices for goods would keep rising and rising and rising. And they did.

Of course, for much of the past year, the big story was the congestion at west coast ports due to both external (China covid breakouts, port closures, changing legislation) and internal factors (lack of port workers, downstream supply jams including trucking and trains, etc) but that has now changed and as the latest Supply Chain Congestion Monitor report from JPMorgan (available to pro subscribers in the usual place) shows, the number of ships at anchor and on approach to L.A. and Long Beach has collapsed since the January high mark, and is back to levels first seen at the start of the covid pandemic.

Why does this matter? Well, for a simple but critical reason: if one year ago we saw the hyperinflationary start of the bullwhip effect, we have entered the terminal phase of the “bullwhip effect”, where plunging inventory-to-sales ratios reverse violently higher, where supply chains unclog suddenly and rapidly amid a sudden chill in the economy, and where prices for so-called “core” goods collapse almost overnight, even as non-core prices (food and energy) explode even higher.

This is how Freight Waves discussed this effect on Friday when commenting on the recent dire earnings (and outlook) from the largest US retailers such as Walmart and Target, which saw their prices crater as management warned that inflation is now crippling demand and snuffing profit margins:

“furniture, home furnishings and appliances, building materials and garden equipment, and a category known as “other general merchandise,” which includes Walmart and Target, among others, reported higher inventory-to-sales ratios, according to government data analyzed by Michigan State.”

How much higher? A quick look at the latest data reveals the following stunning chart of the Inventory to Sales ratio at the Walmarts of the world at the highest level since just before the deflationary flashbang that was the Global Financial Crisis:

Think: widespread inventory liquidations.

As Freight Waves continues, “the change has happened fast, according to Jason Miller, logistics professor at MSU’s Eli Broad College of Business. As of November, inventory-to-sales ratios were at pre-COVID levels, Miller said. They have since exploded upward. Miller said he expects a “cooldown” in retailer order volumes, even if inflation-adjusted sales stay constant, as retailers look to reduce their existing stock.”

And here is the punchline: Miller “also expects retailers to launch major discounting programs to expedite the inventory burn.”

In short: we are about to see the mother of all liquidations as retailers scramble to unload inventory in a time off rampant demand destruction. The immediate result is the freight recession that was first (correctly) forecast by FreightWaves CEO Craig Fuller at the end of March and which is now coming true as the crashing stock price of countless trucker and other freight stocks has demonstrated. Some more on this:

high inventory levels are an expected occurrence and should be welcomed. In a Tuesday note, Amit Mehrotra, transport analyst at Deutsche Bank, said rising buffer stock is part of retailers’ desire to have goods available when consumers scan the shelves. Mehrotra added, however, that the data points translate into a likely slowdown in freight flows in the coming months and quarters.

He said that a recession is already priced into most transportation equities, noting that the shares of most trucking companies are higher over the past 30 days while the broader market is about 7% lower.

The latest data also confirms what FreightWaves’ Fuller said in a subsequent post when he wondered if “Deflation Was Next” as “the Bullwhip was about do the Fed’s job on inflation.”

To be sure, not every product will see its price cut: commodities, whose bullwhip effect take much longer to manifest itself, usually lasting several years in either direction, are only just starting to see their price cycle higher. However, other products – like those carried by the Walmarts and Targets of the world – are about to see a deflationary plunge the likes of which we have not seen since the global financial crisis as retailers commence a voluntary destocking wave the likes of which have not been seen in over a decade.