Authored by Beige Luciano-Adams via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

By now the statistics are familiar: Fentanyl is killing Americans at an unprecedented rate—around 73,000 annually.

For those aged 18 to 45, it is the leading cause of death.

And it’s everywhere—tainting counterfeit pills, poisoning children and adults, addicts and first-time users, overwhelming any potential response. As a deluge of pills and powder flows across the southern border, authorities regularly seize enough fentanyl to kill everyone on earth, several times over.

Into this carnage, a windfall.

Nationwide, more than $50 billion is expected to flow from legal settlements with opioid manufacturers and distributors over the next two decades—with California in line to receive about $4 billion, divvied up among the state and local governments.

This money will now largely go to abating illicit fentanyl—the third wave in an opioid crisis that began with prescription pain medication in the 1990s.

In the first two years, California state programs have primarily used their share for “harm reduction” efforts—including opioid overdose reversal medication, needle exchange, and public education campaigns aimed at destigmatizing drug use.

Nationally, experts and progressive advocates are keeping a close eye on settlement spending, in an effort to avoid mistakes of Big Tobacco settlements and ensure funds go to actual abatement, rather than plugging municipal budgets.

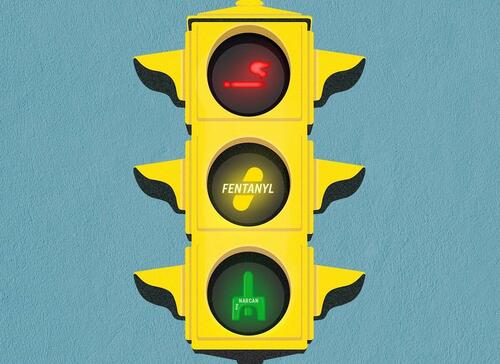

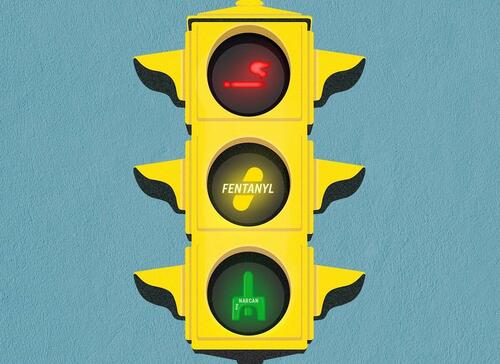

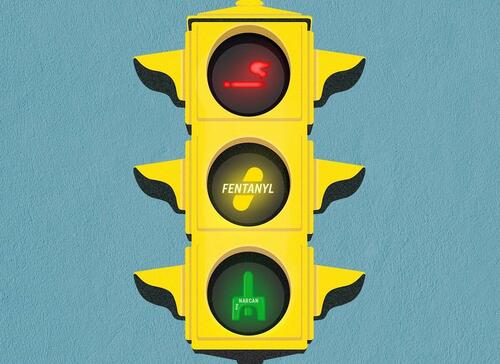

But some wonder if another obvious lesson from the fight against Big Tobacco—in which stigmatization, graphic warnings about the dangers of cigarettes, and enforcement led to a radical decrease in smoking—is missing from the state’s approach to the fentanyl crisis.

California’s Department of Public Health recently gave a San Francisco-based advertising agency $40 million in opioid settlement funds to produce a youth awareness campaign that aims to “meet people where they are” by reducing stigma around using fentanyl and other drugs and encouraging the use of naloxone.

According to state records, the department has also paid that same advertising company nearly $900 million to produce campaigns that expressly stigmatize tobacco use and encourage abstinence from it.

“In general, there is a strange contradiction between [California] Public Health trying hard to stigmatize tobacco smoking while destigmatizing fentanyl use,” Keith Humphreys, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, told The Epoch Times.

By now, Humphreys said, the lessons from Big Tobacco are clear.

“Disapproving of smoking has been a life-saving thing. And we should not be afraid to say to people that using fentanyl is incredibly dangerous and you shouldn’t do it.”

Harm Reduction Movement

Harm reduction is a social justice movement that seeks to reduce drug harms without judging, punishing, or even interfering in drug use. It is an explicit pendulum swing away from the War on Drugs of past decades, which state leaders continue to criticize as a “failed” approach.

Many who are critical of the harm reduction movement in California, where it is orthodoxy—baked into the law—support harm reduction measures like naloxone distribution, medication-assisted treatment, and needle exchange.

Where people tend to disagree is whether hard drugs should be decriminalized and destigmatized, whether those using and selling them should be penalized when they break the law—and especially, whether treatment can be coerced or, as many harm reduction advocates insist, can only happen when and if the person who uses drugs decides they are ready.

Humphreys supports harm reduction measures as part of a comprehensive, multi-pronged approach to the addiction crisis, and champions naloxone. As chair of the Stanford-Lancet Commission, he helped develop a national model for opioid response that recommends overdose rescue medications as “broadly the most lifesaving action policymakers can take.”

But he recognizes the limitations and has criticized the trend, prominent in blue cities, toward de-stigmatization of hard drugs.

“No one stops using drugs because of Narcan,” Humphreys said, citing recent research showing those successfully treated with naloxone—the overdose reversal medicine sold under the brand Narcan—have a 13-fold increase in mortality compared to the general population.

“Twelve percent of people are likely to be dead from their addiction within 12 months of getting the Narcan,” he said.

Further complicating the equation is the fact that non-opioids such as the “zombie drug” xylazine—which does not respond to naloxone—is showing up in nearly 30 percent of all fentanyl powder seizures, and there is no long term research indicating how effective naloxone is after repeated use, or the impact of increasingly higher doses needed to reverse synthetic opioid overdoses.

Meanwhile, naloxone has a shorter half-life than many powerful synthetic opioids—including nitazenes, an “emerging threat” in the U.S. drug supply—meaning people can re-overdose after revival.

California’s current fentanyl awareness campaigns elide the ugly realities of using fentanyl—or meth, which in Los Angeles County last year killed nearly as many people—in favor of a message that works “in alliance with people who use drugs for safer and managed drug use.”

There are no photos of children who died from a single dose, no acknowledgement of the people suffering what amounts to a living death on the streets, no testimony from people who have recovered from their addiction.

“I don’t see one ad in here that says anything about treatment,” noted Gina McDonald, co-founder of Mothers against Drug Addiction and Deaths (MADAAD), a San Francisco-based nonprofit critical of California’s permissive approach to fentanyl.

“I eradicated my risk of overdose by stopping doing drugs—it’s the only foolproof way to prevent overdose. You would think that would be in at least one ad,” said McDonald, a former addict.

According to 2024 statistics published by Mental Health America, a national nonprofit, nearly 83 percent of Californians with a substance use disorder, around five million people, did not receive needed treatment.

Nationally, only Illinois has a higher rate of untreated substance use disorder than California.

McDonald co-founded MADAAD with other mothers who have lost children to the streets—mothers with children currently addicted to fentanyl in places like the Tenderloin and Skid Row.

Their children are the intended targets of the state’s advertising campaigns—and the presumed beneficiaries of funds from a prescription opioid crisis that seeded subsequent heroin and fentanyl epidemics.

McDonald, like most everyone, wants to see Narcan everywhere—in every school and workplace and store—and knows what the shame of addiction feels like.

“I’m not saying we need to stigmatize drug users,” she said.

“But how many times are people going to be Narcan-ed and go back to die another day? It’s usually what happens,” she said. “I don’t know too many people who’ve been Narcan-ed on the street and went into treatment after being resurrected. ... Narcan isn’t dealing with any root cause of why people are using drugs.”

Representatives from influential policy organizations that advocate harm reduction and opiate decriminalization—including the National Harm Reduction Coalition and OpioidSettlementTracker.com—did not respond to inquiries.

An Empathetic Conversation

Robert Marbut, the former executive director of the U.S. Interagency on Homelessness and producer of the forthcoming documentary, “Fentanyl: Death Incorporated,” says the government is under reacting to an existential and continually evolving threat.

“We absolutely have to get into drug education and prevention at a level that we did with cigarettes,” he told The Epoch Times, pointing to the nearly 75-percent reduction in smoking since 1965, when nearly half of Americans smoked; now around 12 percent do.

“[Those campaigns] said cigarette smoking is not cool—it’s dirty, it’s ugly, it’s awful. If you go look at the PSAs, they didn’t go into a sort of kinder, gentler thing. It was hard. It was direct—it was: ‘This is nasty. It’s horrible.’ And governments backed it up with real fines,” Marbut said.

Generally, harm reduction advocates say a softer, empathetic approach is needed to avoid the stigmatization and punitive tones of the War on Drugs. They argue shaming or scaring people who use drugs will prevent them from seeking help.

Representatives of Duncan Channon, the ad agency behind California’s “Facts Fight Fentanyl” campaign, say they avoided the “fear and tragedy” of traditional PSAs in favor of an “approachable and empowering” way to talk about the fentanyl crisis and get people comfortable using naloxone.

“The last thing we are going to do is wag a finger at anybody or follow the failed tactics of ‘Just Say No,’ which has never really worked,” Duncan Channon’s CEO Andy Berkenfield told AdAge last year.

“The state strongly believes—and we are very much in line with them—that our job is to engage in empathetic conversation and ultimately reduce harm,” he told the industry publication.

Fentanyl de-stigmatization campaigns are common across the United States, and California’s opioid-settlement-funded “Unshame CA” campaign reports “measurable changes” in moving the needle on public perception of substance use disorder as a medical condition and naloxone as an everyday resource.

Read the rest here...

Authored by Beige Luciano-Adams via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

By now the statistics are familiar: Fentanyl is killing Americans at an unprecedented rate—around 73,000 annually.

For those aged 18 to 45, it is the leading cause of death.

And it’s everywhere—tainting counterfeit pills, poisoning children and adults, addicts and first-time users, overwhelming any potential response. As a deluge of pills and powder flows across the southern border, authorities regularly seize enough fentanyl to kill everyone on earth, several times over.

Into this carnage, a windfall.

Nationwide, more than $50 billion is expected to flow from legal settlements with opioid manufacturers and distributors over the next two decades—with California in line to receive about $4 billion, divvied up among the state and local governments.

This money will now largely go to abating illicit fentanyl—the third wave in an opioid crisis that began with prescription pain medication in the 1990s.

In the first two years, California state programs have primarily used their share for “harm reduction” efforts—including opioid overdose reversal medication, needle exchange, and public education campaigns aimed at destigmatizing drug use.

Nationally, experts and progressive advocates are keeping a close eye on settlement spending, in an effort to avoid mistakes of Big Tobacco settlements and ensure funds go to actual abatement, rather than plugging municipal budgets.

But some wonder if another obvious lesson from the fight against Big Tobacco—in which stigmatization, graphic warnings about the dangers of cigarettes, and enforcement led to a radical decrease in smoking—is missing from the state’s approach to the fentanyl crisis.

California’s Department of Public Health recently gave a San Francisco-based advertising agency $40 million in opioid settlement funds to produce a youth awareness campaign that aims to “meet people where they are” by reducing stigma around using fentanyl and other drugs and encouraging the use of naloxone.

According to state records, the department has also paid that same advertising company nearly $900 million to produce campaigns that expressly stigmatize tobacco use and encourage abstinence from it.

“In general, there is a strange contradiction between [California] Public Health trying hard to stigmatize tobacco smoking while destigmatizing fentanyl use,” Keith Humphreys, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, told The Epoch Times.

By now, Humphreys said, the lessons from Big Tobacco are clear.

“Disapproving of smoking has been a life-saving thing. And we should not be afraid to say to people that using fentanyl is incredibly dangerous and you shouldn’t do it.”

Harm Reduction Movement

Harm reduction is a social justice movement that seeks to reduce drug harms without judging, punishing, or even interfering in drug use. It is an explicit pendulum swing away from the War on Drugs of past decades, which state leaders continue to criticize as a “failed” approach.

Many who are critical of the harm reduction movement in California, where it is orthodoxy—baked into the law—support harm reduction measures like naloxone distribution, medication-assisted treatment, and needle exchange.

Where people tend to disagree is whether hard drugs should be decriminalized and destigmatized, whether those using and selling them should be penalized when they break the law—and especially, whether treatment can be coerced or, as many harm reduction advocates insist, can only happen when and if the person who uses drugs decides they are ready.

Humphreys supports harm reduction measures as part of a comprehensive, multi-pronged approach to the addiction crisis, and champions naloxone. As chair of the Stanford-Lancet Commission, he helped develop a national model for opioid response that recommends overdose rescue medications as “broadly the most lifesaving action policymakers can take.”

But he recognizes the limitations and has criticized the trend, prominent in blue cities, toward de-stigmatization of hard drugs.

“No one stops using drugs because of Narcan,” Humphreys said, citing recent research showing those successfully treated with naloxone—the overdose reversal medicine sold under the brand Narcan—have a 13-fold increase in mortality compared to the general population.

“Twelve percent of people are likely to be dead from their addiction within 12 months of getting the Narcan,” he said.

Further complicating the equation is the fact that non-opioids such as the “zombie drug” xylazine—which does not respond to naloxone—is showing up in nearly 30 percent of all fentanyl powder seizures, and there is no long term research indicating how effective naloxone is after repeated use, or the impact of increasingly higher doses needed to reverse synthetic opioid overdoses.

Meanwhile, naloxone has a shorter half-life than many powerful synthetic opioids—including nitazenes, an “emerging threat” in the U.S. drug supply—meaning people can re-overdose after revival.

California’s current fentanyl awareness campaigns elide the ugly realities of using fentanyl—or meth, which in Los Angeles County last year killed nearly as many people—in favor of a message that works “in alliance with people who use drugs for safer and managed drug use.”

There are no photos of children who died from a single dose, no acknowledgement of the people suffering what amounts to a living death on the streets, no testimony from people who have recovered from their addiction.

“I don’t see one ad in here that says anything about treatment,” noted Gina McDonald, co-founder of Mothers against Drug Addiction and Deaths (MADAAD), a San Francisco-based nonprofit critical of California’s permissive approach to fentanyl.

“I eradicated my risk of overdose by stopping doing drugs—it’s the only foolproof way to prevent overdose. You would think that would be in at least one ad,” said McDonald, a former addict.

According to 2024 statistics published by Mental Health America, a national nonprofit, nearly 83 percent of Californians with a substance use disorder, around five million people, did not receive needed treatment.

Nationally, only Illinois has a higher rate of untreated substance use disorder than California.

McDonald co-founded MADAAD with other mothers who have lost children to the streets—mothers with children currently addicted to fentanyl in places like the Tenderloin and Skid Row.

Their children are the intended targets of the state’s advertising campaigns—and the presumed beneficiaries of funds from a prescription opioid crisis that seeded subsequent heroin and fentanyl epidemics.

McDonald, like most everyone, wants to see Narcan everywhere—in every school and workplace and store—and knows what the shame of addiction feels like.

“I’m not saying we need to stigmatize drug users,” she said.

“But how many times are people going to be Narcan-ed and go back to die another day? It’s usually what happens,” she said. “I don’t know too many people who’ve been Narcan-ed on the street and went into treatment after being resurrected. … Narcan isn’t dealing with any root cause of why people are using drugs.”

Representatives from influential policy organizations that advocate harm reduction and opiate decriminalization—including the National Harm Reduction Coalition and OpioidSettlementTracker.com—did not respond to inquiries.

An Empathetic Conversation

Robert Marbut, the former executive director of the U.S. Interagency on Homelessness and producer of the forthcoming documentary, “Fentanyl: Death Incorporated,” says the government is under reacting to an existential and continually evolving threat.

“We absolutely have to get into drug education and prevention at a level that we did with cigarettes,” he told The Epoch Times, pointing to the nearly 75-percent reduction in smoking since 1965, when nearly half of Americans smoked; now around 12 percent do.

“[Those campaigns] said cigarette smoking is not cool—it’s dirty, it’s ugly, it’s awful. If you go look at the PSAs, they didn’t go into a sort of kinder, gentler thing. It was hard. It was direct—it was: ‘This is nasty. It’s horrible.’ And governments backed it up with real fines,” Marbut said.

Generally, harm reduction advocates say a softer, empathetic approach is needed to avoid the stigmatization and punitive tones of the War on Drugs. They argue shaming or scaring people who use drugs will prevent them from seeking help.

Representatives of Duncan Channon, the ad agency behind California’s “Facts Fight Fentanyl” campaign, say they avoided the “fear and tragedy” of traditional PSAs in favor of an “approachable and empowering” way to talk about the fentanyl crisis and get people comfortable using naloxone.

“The last thing we are going to do is wag a finger at anybody or follow the failed tactics of ‘Just Say No,’ which has never really worked,” Duncan Channon’s CEO Andy Berkenfield told AdAge last year.

“The state strongly believes—and we are very much in line with them—that our job is to engage in empathetic conversation and ultimately reduce harm,” he told the industry publication.

Fentanyl de-stigmatization campaigns are common across the United States, and California’s opioid-settlement-funded “Unshame CA” campaign reports “measurable changes” in moving the needle on public perception of substance use disorder as a medical condition and naloxone as an everyday resource.

Read the rest here…

Loading…