By Simon White, Bloomberg Markets reporter and analyst

The ECB’s retrospective change in its loan terms is indicative of what to expect at other central banks as they try to preempt political pressure and any circumscription of their independence.

In the QE years, the ECB offered loans to euro-zone banks with conditions attached to encourage the banks to lend more to the real economy (TLTROs). The loans had very favorable rates, as low as -1%. However, with rates in the region rising and now above zero, banks are able to repark the loans at the ECB and earn a positive spread for taking no risk.

Today’s ECB announcement included reducing the amount banks earn on their minimum (required) reserves, and also making retrospective changes to the TLTROs’ terms. The ECB is encouraging early repayment of the loans and, for those who do not take up this offer, the rate payable will be recalibrated to an average rate calculated between Nov. 23 and when the loan is repaid (i.e almost certainly higher).

The ECB is trying to head off political interference from banks being paid billions of euros, risk free, while a cost-of-living and energy crisis engulfs the region. The problem is not confined to Europe. Years of QE have led to trillions of dollars of interest-bearing central-bank liabilities that, now that rates are well above zero in the US, UK and Europe, are incurring ever greater costs.

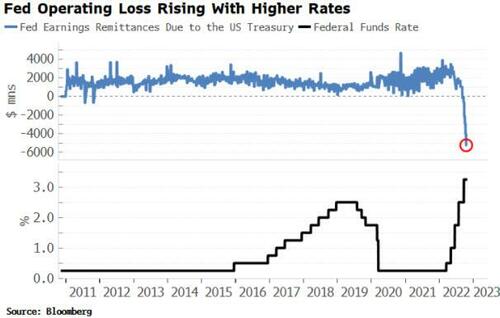

The Fed is now “making a loss,” as what it pays out in interest significantly exceeds what it receives on its assets. It is not a real loss, but it means the Fed will not start remitting money to the Treasury again until this loss is made up for by positive income. Even though the Fed cannot go bankrupt (in dollar terms), the political optics on this may start to look bad, too (ZH: as we first discussed this in "The Fed Is Now Paying $500 Million To A Handful Of Banks Every Day, And Suddenly Has A Very Big Problem").

Central banks had much less independence in the inflationary 1970s. This led to “go-stop” monetary policy whereby a central bank tightened to “stop” the economy, but then was quickly in “go” mode again as political pressure mounted as unemployment rose.

This is sub-optimal, along with the ECB risking its credibility by reneging on previous agreements. Unfortunately sub-optimal is about as much as can be hoped for as markets and the economy are upended by elevated and increasingly entrenched inflation.

Central banks had much less independence in the inflationary 1970s. This led to “go-stop” monetary policy whereby a central bank tightened to “stop” the economy, but then was quickly in “go” mode again as political pressure mounted as unemployment rose.

This is sub-optimal, along with the ECB risking its credibility by reneging on previous agreements. Unfortunately sub-optimal is about as much as can be hoped for as markets and the economy are upended by elevated and increasingly entrenched inflation.

By Simon White, Bloomberg Markets reporter and analyst

The ECB’s retrospective change in its loan terms is indicative of what to expect at other central banks as they try to preempt political pressure and any circumscription of their independence.

In the QE years, the ECB offered loans to euro-zone banks with conditions attached to encourage the banks to lend more to the real economy (TLTROs). The loans had very favorable rates, as low as -1%. However, with rates in the region rising and now above zero, banks are able to repark the loans at the ECB and earn a positive spread for taking no risk.

Today’s ECB announcement included reducing the amount banks earn on their minimum (required) reserves, and also making retrospective changes to the TLTROs’ terms. The ECB is encouraging early repayment of the loans and, for those who do not take up this offer, the rate payable will be recalibrated to an average rate calculated between Nov. 23 and when the loan is repaid (i.e almost certainly higher).

The ECB is trying to head off political interference from banks being paid billions of euros, risk free, while a cost-of-living and energy crisis engulfs the region. The problem is not confined to Europe. Years of QE have led to trillions of dollars of interest-bearing central-bank liabilities that, now that rates are well above zero in the US, UK and Europe, are incurring ever greater costs.

The Fed is now “making a loss,” as what it pays out in interest significantly exceeds what it receives on its assets. It is not a real loss, but it means the Fed will not start remitting money to the Treasury again until this loss is made up for by positive income. Even though the Fed cannot go bankrupt (in dollar terms), the political optics on this may start to look bad, too (ZH: as we first discussed this in “The Fed Is Now Paying $500 Million To A Handful Of Banks Every Day, And Suddenly Has A Very Big Problem“).

Central banks had much less independence in the inflationary 1970s. This led to “go-stop” monetary policy whereby a central bank tightened to “stop” the economy, but then was quickly in “go” mode again as political pressure mounted as unemployment rose.

This is sub-optimal, along with the ECB risking its credibility by reneging on previous agreements. Unfortunately sub-optimal is about as much as can be hoped for as markets and the economy are upended by elevated and increasingly entrenched inflation.

Central banks had much less independence in the inflationary 1970s. This led to “go-stop” monetary policy whereby a central bank tightened to “stop” the economy, but then was quickly in “go” mode again as political pressure mounted as unemployment rose.

This is sub-optimal, along with the ECB risking its credibility by reneging on previous agreements. Unfortunately sub-optimal is about as much as can be hoped for as markets and the economy are upended by elevated and increasingly entrenched inflation.