By Simon White, Bloomberg Markets Live commentator and reporter

While the direction of Europe’s economy continues to be a hostage to Russian energy -- as today’s dispiriting PMI numbers attest -- it is the Asian nations of China and Japan who are in a position to alleviate Europe’s capital-outflow problem and stabilize the euro.

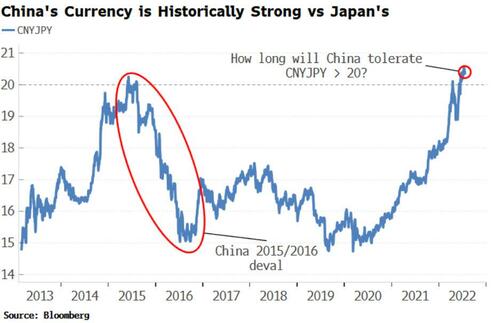

The BoJ’s single-minded policy to keep rates low when the rest of the world is raising them has led to the yen being at its weakest level versus the yuan since the China deval in 1994.

How long will China tolerate this? China is Japan’s largest trading partner, Japan is China’s second largest trading partner, and China already runs a trade deficit with Japan. Further, both countries have the US as one of their largest trading partners.

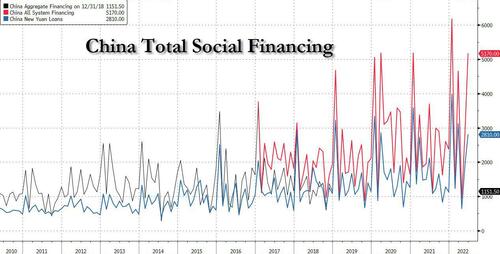

China has been incrementally easing policy as it seeks to countervail the draconian effects of its Zero Covid policy, with fiscal, credit and monetary measures announced in recent months. Policymakers are still resisting flood-like stimulus, but the broadest measure of credit in China, Total Social Financing (TSF), is beginning to show signs of steady growth. Trade competitiveness considerations are likely to keep China on the easing track.

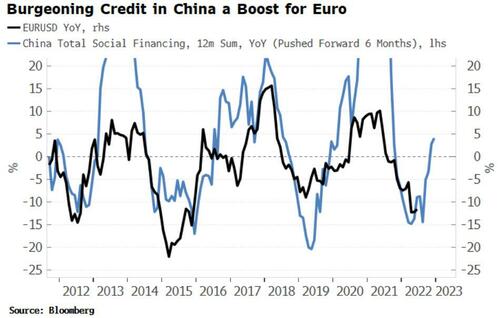

Europe’s economy is heavily tied to China’s, and cyclical improvements in China’s growth tend to lead to rises in Europe’s growth over the next six months or so. Thus the rise in TSF points to a stronger euro in the coming months.

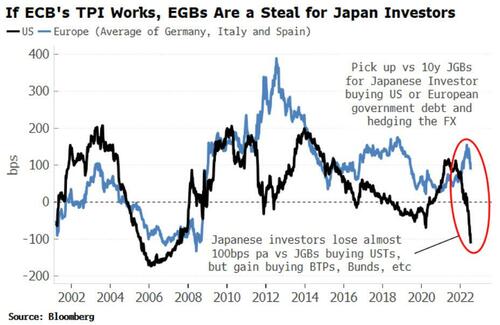

The suppression of JGB yields while the Fed has been hiking aggressively has also led to USTs becoming singularly unattractive for Japanese investors. As US short-term rates have risen sharply, hedging costs have followed suit, with the result that once a Japanese-based investor has sold their yen using an FX forward and bought USTs with the proceeds, they are down 100bps a year compared with if they had just bought a 10y JGB.

On the other hand, the comparatively timid rate hikes from the ECB (it has hiked 50 bps this year versus 150 bps in the US, with an extra 60 bps priced in from the Fed compared to the ECB by the end of this year) mean that European government bonds still provide a positive uplift versus JGBs.

So will the Japanese come running to scoop up BTPs, OATs and bunds? This really depends on the success of the latest TLA (three-lettered acronym) coined by the ECB, the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). Designed to prevent bond spreads from blowing out in Europe’s energy crisis, there is some ambiguity around what it would take to trigger it.

But like all such programs, its existence alone is hopefully enough to prevent it ever actually being used. If the Japanese think so and want to take advantage of yields that are highly attractive to them, then the ECB’s coining of yet another acronym will not have been in vain.

By Simon White, Bloomberg Markets Live commentator and reporter

While the direction of Europe’s economy continues to be a hostage to Russian energy — as today’s dispiriting PMI numbers attest — it is the Asian nations of China and Japan who are in a position to alleviate Europe’s capital-outflow problem and stabilize the euro.

The BoJ’s single-minded policy to keep rates low when the rest of the world is raising them has led to the yen being at its weakest level versus the yuan since the China deval in 1994.

How long will China tolerate this? China is Japan’s largest trading partner, Japan is China’s second largest trading partner, and China already runs a trade deficit with Japan. Further, both countries have the US as one of their largest trading partners.

China has been incrementally easing policy as it seeks to countervail the draconian effects of its Zero Covid policy, with fiscal, credit and monetary measures announced in recent months. Policymakers are still resisting flood-like stimulus, but the broadest measure of credit in China, Total Social Financing (TSF), is beginning to show signs of steady growth. Trade competitiveness considerations are likely to keep China on the easing track.

Europe’s economy is heavily tied to China’s, and cyclical improvements in China’s growth tend to lead to rises in Europe’s growth over the next six months or so. Thus the rise in TSF points to a stronger euro in the coming months.

The suppression of JGB yields while the Fed has been hiking aggressively has also led to USTs becoming singularly unattractive for Japanese investors. As US short-term rates have risen sharply, hedging costs have followed suit, with the result that once a Japanese-based investor has sold their yen using an FX forward and bought USTs with the proceeds, they are down 100bps a year compared with if they had just bought a 10y JGB.

On the other hand, the comparatively timid rate hikes from the ECB (it has hiked 50 bps this year versus 150 bps in the US, with an extra 60 bps priced in from the Fed compared to the ECB by the end of this year) mean that European government bonds still provide a positive uplift versus JGBs.

So will the Japanese come running to scoop up BTPs, OATs and bunds? This really depends on the success of the latest TLA (three-lettered acronym) coined by the ECB, the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). Designed to prevent bond spreads from blowing out in Europe’s energy crisis, there is some ambiguity around what it would take to trigger it.

But like all such programs, its existence alone is hopefully enough to prevent it ever actually being used. If the Japanese think so and want to take advantage of yields that are highly attractive to them, then the ECB’s coining of yet another acronym will not have been in vain.