Submitted by Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca

Last September, after China’s second-largest property developer, Evergrande Group, missed $131 million in interest payments, Beijing promised to rein in risky real-estate speculation. We didn’t buy it. As we wrote in November, Chinese leaders rely on frothy housing markets and lending growth to meet their politically determined annual GDP growth targets. Serious housing reform was not in the cards.

Sure enough, Beijing soon revealed that the promise was a head-fake. In January, the government moved to make it easier for developers to pay creditors using pre-construction homebuyer funds held in escrow. In March, the National People’s Congress killed plans to introduce a national property tax and other structural reforms to reduce property speculation. Municipal authorities have subsidized young buyers’ home purchases, directed state-owned banks to slash mortgage rates, and eased home down-payment requirements.

The state-controlled press says it is all working perfectly—speculation is being stamped out, and the housing market is “stable.” Yet home sales are plunging.

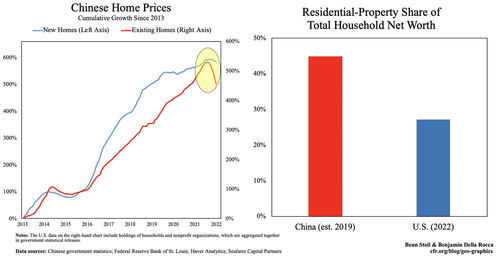

So how does the government square this circle? It points to data showing steady prices for new homes. Our left-hand graphic above confirms this fact. But it also shows a steep decline—the steepest on record—in prices for existing homes.

What is happening? The government cares less about prices of existing homes than new-home prices, since over-leveraged developers make their money selling new units. So, not surprisingly, it is betting the house on keeping new homes popular and profitable.

Chinese cities have been imposing price floors and prohibiting “malicious price cuts” on new construction. They have been offering generous consumer-goods vouchers and tax cuts to buyers of new properties. All of this costly window-dressing is keeping new-home prices up and overleveraged developers afloat, even as the market for existing homes tanks. Still, real-estate analysts and Chinese developers alike widely expect new-home prices to head south soon enough.

Falling house prices affect GDP through the so-called wealth effect—that is, consumers’ tendency to cut spending when their assets fall in value. A $100 decline in housing-market net worth, according to one U.S.-based study, lowers consumption by $2.50-5.00. In China, the housing wealth effect is likely at least this large. As the right-hand chart above shows, homes represent roughly 45 percent of Chinese household net worth. (In some cities, it is more like 70 percent.) That compares with just 27 percent in the United States.

What does all this mean for China’s economy? If existing-home price declines bring a wealth effect at the upper end of the range above, then we would expect recent changes alone to shave roughly half a percent off China’s 2022 GDP growth. Last month, owing to omicron’s spread, the IMF revised China’s 2022 growth forecast down to 4.4 percent, 1.1 percentage points below the government’s target, although home-price effects do not seem to be part of their equation. All else equal, something below 4 percent is more likely. Of course, President Xi may be unwilling to accept 4 percent growth—in which case we can expect yet further measures to juice borrowing and home prices.

Eventually, unsustainable debt becomes—well, unsustainable. At that point, there is a financial crisis or productivity collapse that crushes growth. Defining “eventually,” of course, is the big challenge.

Submitted by Benn Steil and Benjamin Della Rocca

Last September, after China’s second-largest property developer, Evergrande Group, missed $131 million in interest payments, Beijing promised to rein in risky real-estate speculation. We didn’t buy it. As we wrote in November, Chinese leaders rely on frothy housing markets and lending growth to meet their politically determined annual GDP growth targets. Serious housing reform was not in the cards.

Sure enough, Beijing soon revealed that the promise was a head-fake. In January, the government moved to make it easier for developers to pay creditors using pre-construction homebuyer funds held in escrow. In March, the National People’s Congress killed plans to introduce a national property tax and other structural reforms to reduce property speculation. Municipal authorities have subsidized young buyers’ home purchases, directed state-owned banks to slash mortgage rates, and eased home down-payment requirements.

The state-controlled press says it is all working perfectly—speculation is being stamped out, and the housing market is “stable.” Yet home sales are plunging.

So how does the government square this circle? It points to data showing steady prices for new homes. Our left-hand graphic above confirms this fact. But it also shows a steep decline—the steepest on record—in prices for existing homes.

What is happening? The government cares less about prices of existing homes than new-home prices, since over-leveraged developers make their money selling new units. So, not surprisingly, it is betting the house on keeping new homes popular and profitable.

Chinese cities have been imposing price floors and prohibiting “malicious price cuts” on new construction. They have been offering generous consumer-goods vouchers and tax cuts to buyers of new properties. All of this costly window-dressing is keeping new-home prices up and overleveraged developers afloat, even as the market for existing homes tanks. Still, real-estate analysts and Chinese developers alike widely expect new-home prices to head south soon enough.

Falling house prices affect GDP through the so-called wealth effect—that is, consumers’ tendency to cut spending when their assets fall in value. A $100 decline in housing-market net worth, according to one U.S.-based study, lowers consumption by $2.50-5.00. In China, the housing wealth effect is likely at least this large. As the right-hand chart above shows, homes represent roughly 45 percent of Chinese household net worth. (In some cities, it is more like 70 percent.) That compares with just 27 percent in the United States.

What does all this mean for China’s economy? If existing-home price declines bring a wealth effect at the upper end of the range above, then we would expect recent changes alone to shave roughly half a percent off China’s 2022 GDP growth. Last month, owing to omicron’s spread, the IMF revised China’s 2022 growth forecast down to 4.4 percent, 1.1 percentage points below the government’s target, although home-price effects do not seem to be part of their equation. All else equal, something below 4 percent is more likely. Of course, President Xi may be unwilling to accept 4 percent growth—in which case we can expect yet further measures to juice borrowing and home prices.

Eventually, unsustainable debt becomes—well, unsustainable. At that point, there is a financial crisis or productivity collapse that crushes growth. Defining “eventually,” of course, is the big challenge.