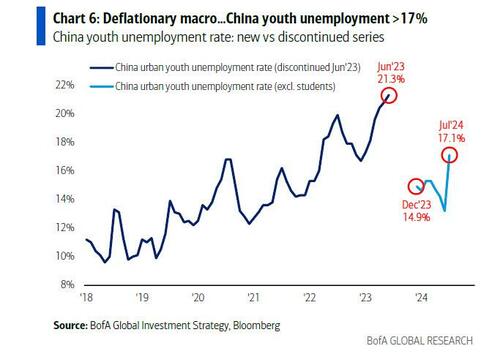

A few weeks ago, we warned that the entire Chinese experiment was on the verge of collapse because while on one hand the welfare state was crumbling due to Beijing's stubborn insistence not to stimulate the economy at any cost (normally, it would be admirable to be so stubbornly insistent on austerity but when austerity threatens social collapse, it may be time to reassess), this was accentuated by an explosion in social unrest as youth unemployment soared, and worker strikes surged across the nation.

While we detailed the various reasons that had pushed China to the edge of the abyss, one section was especially notable: our preview of what was the logical next step in China's belt-tightening ways - raising the retirement age - and the obvious blowback storm it would generate.

In a key socioeconomic planning meeting concluded last month, the government vowed to improve the social security system by addressing the restrictions faced by migration workers. In response to the country's aging population, it added that the statutory retirement age -- currently 60 years for men and between 50 and 55 for women -- would be raised gradually and voluntarily.

To this we added that there is, of course, zero historical record of a "centrally-planned civilization that has managed to raise the retirement age either "voluntarily" and without clashes, violence, and collapse in social cohesion, precisely the three things that Beijing fears the most."

We concluded by quoting Yun Zhou, a social demographer and family sociologist at the University of Michigan, who warned that "for China's urban workers, the talk of raising retirement ages is felt as a delayed, if not broken, promise of social welfare coverage" to which we counteded:

Which is precisely why Beijing will have no choice but to blink in the end, and that will mean unleashing a much delayed stimulus bazooka that likes of which have not been seen yet.

Fast-forward to today, when Beijing did just as we expected it would and, in a last ditch attempt to delay the "stimulus bazooka", announced it would raise the retirement age for the first time since 1978, a move that will help stem a rapid decline in the labor force but risk angering workers already wrestling with a slowing economy.

Top lawmakers endorsed a plan to delay retirement for employees by as long as five years, Xinhua News Agency reported Friday. Men will retire at 63 instead of 60. Women will retire at 55 instead of 50 for ordinary workers, and 58 instead of 55 for those in management positions. Come to think of it, it is absolutely insane that in China 50 is the retirement age for women. But now that China has finally figured out the brutal reality of its demographic implosion, the money printer comes next.

The retirement change will take place over 15 years starting January, and will allow more people to work longer. This could boost productivity to address the challenges of an aging population, although it is much more likely that all today's decision will do is spark public anger, and add to the ire from an economy growing at the worst pace in five quarters.

“The timeline of raising the retirement age is pretty gradual. Policymakers probably have taken into account the potential negative impact and calibrated that carefully,” said Michelle Lam, China economist at Societe Generale. Actually sorry Michelle, but nobody in Beijing has calibrated anything as the coming violence will demonstrate.

Shares of companies providing health and elderly care jumped, with Shanghai Everjoy Health rising by the daily limit of 10%. Chalkis Health Industry and Youngy Health both gained more than 6%.

“People may face more health problems if the retirement age is raised. And the pressure of supporting parents may require more elderly care institutions to share the burden,” said Shen Meng

China’s retirement age had been among the world’s lowest - even below that of socialist paradise France - despite significantly increased life expectancy over the decades. A bigger tax base and delayed access to benefits will relieve the pressure on the government to fund pensions as the elderly population rapidly expands.

The retirement age hike is aimed at “adapting to the new situation of demographic development in China, and fully developing and utilizing human resources,” according to the decision by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress.

The approval followed the previously reported July announcement by the ruling Communist Party that the retirement age will rise in a “voluntary, flexible manner.” Flexible? Maybe. Voluntary? No chance in hell: previous efforts to raise the threshold had failed in the face of public opposition.

The Friday decision left countless people fuming over working into an older age, as well as those who fear greater competition in the job market.

“Are you asking me, when I’m 60, to compete with young people for jobs?” a Weibo user said on the X-like social media platform, where the news was the top trending item and garnered more than 530 million views as of Friday afternoon.

Some also complained about employers’ discrimination against older job candidates, a problem that the government has long vowed to address. Authorities acknowledged the potential short-term pressure on the job market at a press briefing on Friday. Li Zhong, vice minister at the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, said the gradual pace of the change should lead to a “muted” effect on youth employment, which as everyone knows China stopped reporting last year, only to replace it with a new, "revised" data series... which also just hit a record high.

Just to make sure the outraged workers are even angrier, China's top legislative body also ruled that starting 2030, workers will need to contribute to their pension accounts for a longer period before they’re eligible to receive payout. This requirement will increase gradually from 15 to 20 years, Bloomberg reported.

“The sustainability of the pension system may be the main consideration behind the move,” said Ding Shuang, chief economist for Greater China and North Asia at Standard Chartered. “Even though the move will increase pressure for the job market, in the long term it helps mitigate the impact from declines in the working-age population.”

Adding insult to injury, lawmakers also called on officials to actively respond to the aging population, protect workers’ rights and improve elderly care. Additionally, it empowered the State Council, China’s cabinet, to adjust these measures as needed.

In other words, absolutely nothing will happen, except for even more government workers being thrown at an unsolvable problem, and even more corruption.

As China’s life expectancy has risen, delaying retirement has become more important to offset the demographic challenges from its decades-long enforcement of a one-child policy, which left a generation of single children supporting a large elderly population. Today, the average Chinese lives to 78 from 66 four decades ago.

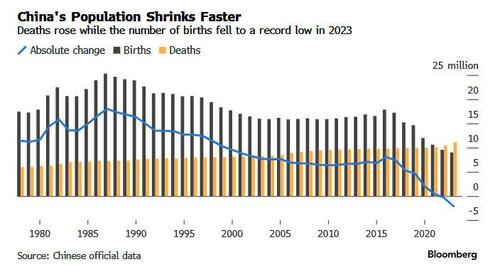

People aged 65 and older are expected to make up 30% of the population by around 2035 from 14.2% in 2021, according to a report by state broadcaster CCTV on Tuesday. Authorities’ efforts to encourage births have so far done little to reverse the demographic shift, with birth rate falling to a record last year.

“When I was born they said there were too many. When I gave birth they said there were too few. When I wanted to work they said I was too old. And when I retire they say I’m too young,” another Weibo user said.

A few weeks ago, we warned that the entire Chinese experiment was on the verge of collapse because while on one hand the welfare state was crumbling due to Beijing’s stubborn insistence not to stimulate the economy at any cost (normally, it would be admirable to be so stubbornly insistent on austerity but when austerity threatens social collapse, it may be time to reassess), this was accentuated by an explosion in social unrest as youth unemployment soared, and worker strikes surged across the nation.

While we detailed the various reasons that had pushed China to the edge of the abyss, one section was especially notable: our preview of what was the logical next step in China’s belt-tightening ways – raising the retirement age – and the obvious blowback storm it would generate.

In a key socioeconomic planning meeting concluded last month, the government vowed to improve the social security system by addressing the restrictions faced by migration workers. In response to the country’s aging population, it added that the statutory retirement age — currently 60 years for men and between 50 and 55 for women — would be raised gradually and voluntarily.

To this we added that there is, of course, zero historical record of a “centrally-planned civilization that has managed to raise the retirement age either “voluntarily” and without clashes, violence, and collapse in social cohesion, precisely the three things that Beijing fears the most.”

We concluded by quoting Yun Zhou, a social demographer and family sociologist at the University of Michigan, who warned that “for China’s urban workers, the talk of raising retirement ages is felt as a delayed, if not broken, promise of social welfare coverage” to which we counteded:

Which is precisely why Beijing will have no choice but to blink in the end, and that will mean unleashing a much delayed stimulus bazooka that likes of which have not been seen yet.

Fast-forward to today, when Beijing did just as we expected it would and, in a last ditch attempt to delay the “stimulus bazooka”, announced it would raise the retirement age for the first time since 1978, a move that will help stem a rapid decline in the labor force but risk angering workers already wrestling with a slowing economy.

Top lawmakers endorsed a plan to delay retirement for employees by as long as five years, Xinhua News Agency reported Friday. Men will retire at 63 instead of 60. Women will retire at 55 instead of 50 for ordinary workers, and 58 instead of 55 for those in management positions. Come to think of it, it is absolutely insane that in China 50 is the retirement age for women. But now that China has finally figured out the brutal reality of its demographic implosion, the money printer comes next.

The retirement change will take place over 15 years starting January, and will allow more people to work longer. This could boost productivity to address the challenges of an aging population, although it is much more likely that all today’s decision will do is spark public anger, and add to the ire from an economy growing at the worst pace in five quarters.

“The timeline of raising the retirement age is pretty gradual. Policymakers probably have taken into account the potential negative impact and calibrated that carefully,” said Michelle Lam, China economist at Societe Generale. Actually sorry Michelle, but nobody in Beijing has calibrated anything as the coming violence will demonstrate.

Shares of companies providing health and elderly care jumped, with Shanghai Everjoy Health rising by the daily limit of 10%. Chalkis Health Industry and Youngy Health both gained more than 6%.

“People may face more health problems if the retirement age is raised. And the pressure of supporting parents may require more elderly care institutions to share the burden,” said Shen Meng

China’s retirement age had been among the world’s lowest – even below that of socialist paradise France – despite significantly increased life expectancy over the decades. A bigger tax base and delayed access to benefits will relieve the pressure on the government to fund pensions as the elderly population rapidly expands.

The retirement age hike is aimed at “adapting to the new situation of demographic development in China, and fully developing and utilizing human resources,” according to the decision by the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress.

The approval followed the previously reported July announcement by the ruling Communist Party that the retirement age will rise in a “voluntary, flexible manner.” Flexible? Maybe. Voluntary? No chance in hell: previous efforts to raise the threshold had failed in the face of public opposition.

The Friday decision left countless people fuming over working into an older age, as well as those who fear greater competition in the job market.

“Are you asking me, when I’m 60, to compete with young people for jobs?” a Weibo user said on the X-like social media platform, where the news was the top trending item and garnered more than 530 million views as of Friday afternoon.

Some also complained about employers’ discrimination against older job candidates, a problem that the government has long vowed to address. Authorities acknowledged the potential short-term pressure on the job market at a press briefing on Friday. Li Zhong, vice minister at the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, said the gradual pace of the change should lead to a “muted” effect on youth employment, which as everyone knows China stopped reporting last year, only to replace it with a new, “revised” data series… which also just hit a record high.

Just to make sure the outraged workers are even angrier, China’s top legislative body also ruled that starting 2030, workers will need to contribute to their pension accounts for a longer period before they’re eligible to receive payout. This requirement will increase gradually from 15 to 20 years, Bloomberg reported.

“The sustainability of the pension system may be the main consideration behind the move,” said Ding Shuang, chief economist for Greater China and North Asia at Standard Chartered. “Even though the move will increase pressure for the job market, in the long term it helps mitigate the impact from declines in the working-age population.”

Adding insult to injury, lawmakers also called on officials to actively respond to the aging population, protect workers’ rights and improve elderly care. Additionally, it empowered the State Council, China’s cabinet, to adjust these measures as needed.

In other words, absolutely nothing will happen, except for even more government workers being thrown at an unsolvable problem, and even more corruption.

As China’s life expectancy has risen, delaying retirement has become more important to offset the demographic challenges from its decades-long enforcement of a one-child policy, which left a generation of single children supporting a large elderly population. Today, the average Chinese lives to 78 from 66 four decades ago.

People aged 65 and older are expected to make up 30% of the population by around 2035 from 14.2% in 2021, according to a report by state broadcaster CCTV on Tuesday. Authorities’ efforts to encourage births have so far done little to reverse the demographic shift, with birth rate falling to a record last year.

“When I was born they said there were too many. When I gave birth they said there were too few. When I wanted to work they said I was too old. And when I retire they say I’m too young,” another Weibo user said.

Loading…