Earlier today, Goldman's head of hedge fund sales Tony Pasquariello observed that "to this point in the sequence, I’d argue the slowdown in China had been a net positive for US equities -- with specific regard to the disinflationary impulse and the flow of capital. That said, coming out of a week that featured another disappointing set of data -- and another dose of CNH weakness -- it now feels like China growth fears can provoke a more global risk-off dynamic."

Well, if Tony is right, then watch out below, because the bad news out of China has become a firehose that is only getting more powerful with every passing day, especially if one ignores the fake official data and looks at the truth beneath the surface.

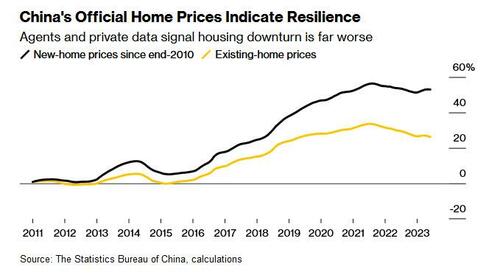

Consider China’s official housing market statistics, which despite falling sequentially for the first time in 2023 in July, have first been remarkably resilient in the face of tepid economic growth and record defaults by developers. New-home prices have slipped just 2.4% from a high in August 2021, government figures show, while those for existing homes have dropped 6%.

Of course, China's official data is almost as credible as that of the Biden Department of Labor; and indeed, the picture emerging from property agents and private data providers is far more dire.

As Bloomberg notes, these figures show existing-home prices falling at least 15% in prime neighborhoods of major metropolitan areas like Shanghai and Shenzhen, as well as in more than half of China’s tier-2 and tier-3 cities.

- Existing homes near Alibaba’s headquarters in Hangzhou have dropped about 25% from late 2021 highs, according to local agents.

- In Lianyang, a downtown area popular with expats and financiers in Shanghai, residential prices have slid 15% to 20% from record highs in mid-2021.

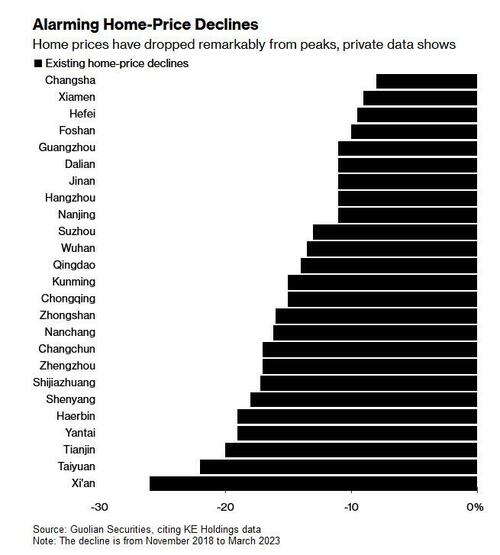

Even as of March, before the latest property market crisis, more than half of tier-2 and tier-3 cities saw existing-home prices fall more than 15% from peaks, Guolian Securities economists wrote in a report citing data by existing housing transaction services provider KE Holdings Inc. Actual declines from peaks could be sharper, as the agency only compiles data starting November 2018, the economists cautioned

Top-tier cities, once considered resilient against a housing downturn, are also not immune. Prices of existing homes in at least five popular districts of Shenzhen have slumped 15% in the past three years, according to a July report by property research institute Leyoujia. The southern hub is the country’s least affordable housing market.

It's hardly rocket science what is going on here: industry insiders and economists say China’s official home-price indexes are understating the depth of the downturn (by a lot) in part because of longstanding methodologies that struggle to capture market turning points, in part because - well - all of China's data is propaganda.

That’s heightening concern among investors about the availability of timely economic data in China, where access to some information has become increasingly restricted under the government of President Xi Jinping. It also raises questions about whether policy makers themselves have an accurate understanding of the market as they devise measures to prop up demand. Another risk is that wary homebuyers stay on the sidelines, waiting for price declines to show up in the data before they step in.

Analysts say the methodology, which partly relies on surveys rather than price data from transactions, helps authorities to smooth the trend and to avoid large swings. By contrast, in the US, the widely cited S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller indexes use home-price data collected at local deed recording offices across the country.

For Henry Chin, who’s spent more than 20 years researching global real estate markets, the data’s source and accuracy are critical.

“Home-price data in many countries are based on total market transactions, yet China uses selective samples,” said Chin, the head of research for Asia Pacific at CBRE Group Inc. “When a market goes down, the true market condition is hard to be reflected in such data.”

China’s statistics bureau has said in an online explanation that raw data on new-home prices is based on all sales and purchases registered in local housing transaction bodies. Existing-home prices, though, are based on both sales of key projects and surveys, it said. The NBS uses the Laspeyres price index, a common formula used worldwide, to calculate its 70-city home-price gauge, the statistics bureau told Bloomberg. Market watchers say the methodology on sampling and index calculation remain ambiguous.

Survey-based data “serves a purpose avoiding extreme fluctuation,” said Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief Asia Pacific economist at Natixis SA in Hong Kong. “But when people are wary that prices are falling even more, thus not buying, such data defeats its own purpose.”

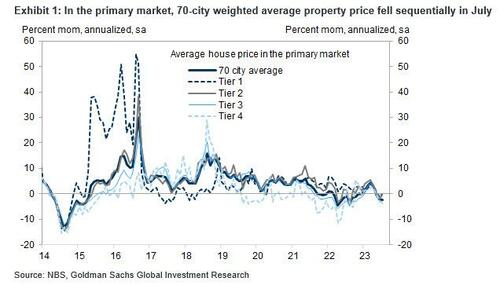

This partly explains why home price changes implied by official and private sources appear inconsistent with market perceptions on some occasions, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists said in a July report called “Understanding differences in China’s home price measures.”

Translation: nobody believes Chinese data any more.

Which is very bad for Beijing, since nobody will buy real estate - China's biggest asset by orders of magnitude - if there is zero confidence in what the accurate price is, and until there is some comfort that the price drops are over.

What is worse is that even China’s state-owned property developers are now warning of widespread losses, fueling concerns that the housing crisis is expanding from the private sector to companies with government backing.

In a separate Bloomberg report, we learn that 18 out of 38 state-owned enterprise builders listed in Hong Kong and the mainland reported preliminary losses in the six months ended June 30, up from 11 that warned of full-year losses in 2022, according to a Bloomberg tally based on corporate filings. Two years ago, only four firms with controlling or major state shareholdings posted losses.

Some of the state-owned developers have cited declining profit margins and heavier provisions to write down asset values stemming from the housing woes. Companies seeing losses include some of the biggest developers owned by the central government. Shenzhen Overseas Chinese Town warned of a loss of as much as 1.7 billion yuan ($233 million), partly due to a marketing strategy to speed up home sales. That followed a loss in the second half of last year, which was its first since its 1997 listing.

Players in economically stronger cities are also suffering. Everbright Jiabao Co., operated by a local state asset manager in Shanghai’s Jiading district, said it expects its first ever half-year loss since its listing.

The warnings signal state builders are no longer immune from the two-year housing slump that has weakened the economy and triggered dozens of defaults by private peers, with speculation that Country Garden Holdings may be next, a collapse which would be more devastating than the Evergrande collapse two years ago. Authorities have in recent weeks stepped up pledges to support the property sector, though analysts are skeptical that the measures will be enough to revive the market anytime soon.

“China’s property slowdown is already hurting all developers, including the large government-linked ones,” said Zerlina Zeng, senior credit analyst at CreditSights Singapore. “We do not expect the situation to materially improve in the second half.”

That said, according to Bloomberg Intelligence credit analyst Andrew Chan, the loss warnings aren’t necessarily all doom and gloom for state developers - it’s natural that they would write down their inventories to reflect the slump in values, he notes.

“SOEs could be kitchen-sinking their results for better years ahead,” Chan said. “The key is whether they can still receive liquidity support from banks. For smaller SOE developers, it will be a case-by-case situation.”

But losses will reduce their scope to take on unfinished projects left by defaulted private-sector firms, further denting homebuyer sentiment. Chinese regulators see asset sales as a key step to easing the debt crisis, as President Xi Jinping’s government largely steers clear of direct bailouts.

“Sector consolidation anyhow takes time,” CreditSights’ Zeng said. “Especially in a property downturn when acquirers, such as SOEs and asset management firms, are demanding better valuations and sellers are not willing to dispose at a deep discount.”

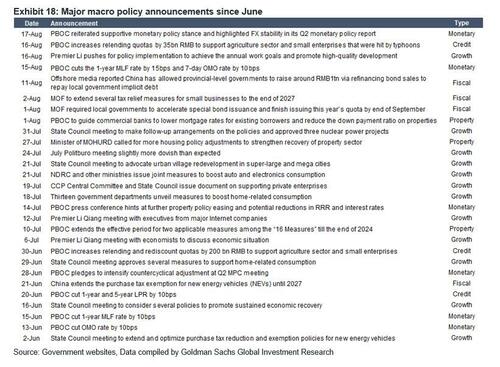

One policy tool being used to revive the housing market and the broader economy is interest-rate cuts. In a surprise move, the People’s Bank of China on Tuesday made the steepest cut in three years on the rate on its one-year loans. The central bank has also encouraged lenders to lower mortgage rates, Jingyang Chen, Asia FX strategist at HSBC Holdings Plc, said earlier this month.

As of June, 100 out of 343 Chinese cities have lowered the rate floor of new-home mortgages or removed the minimum required, the PBOC said in its quarterly monetary policy report on Thursday. That has brought the nation’s average mortgage rate to 4.11% in June, down 0.51 percentage point from a year earlier.

Earlier today, Goldman’s head of hedge fund sales Tony Pasquariello observed that “to this point in the sequence, I’d argue the slowdown in China had been a net positive for US equities — with specific regard to the disinflationary impulse and the flow of capital. That said, coming out of a week that featured another disappointing set of data — and another dose of CNH weakness — it now feels like China growth fears can provoke a more global risk-off dynamic.“

Well, if Tony is right, then watch out below, because the bad news out of China has become a firehose that is only getting more powerful with every passing day, especially if one ignores the fake official data and looks at the truth beneath the surface.

Consider China’s official housing market statistics, which despite falling sequentially for the first time in 2023 in July, have first been remarkably resilient in the face of tepid economic growth and record defaults by developers. New-home prices have slipped just 2.4% from a high in August 2021, government figures show, while those for existing homes have dropped 6%.

Of course, China’s official data is almost as credible as that of the Biden Department of Labor; and indeed, the picture emerging from property agents and private data providers is far more dire.

As Bloomberg notes, these figures show existing-home prices falling at least 15% in prime neighborhoods of major metropolitan areas like Shanghai and Shenzhen, as well as in more than half of China’s tier-2 and tier-3 cities.

- Existing homes near Alibaba’s headquarters in Hangzhou have dropped about 25% from late 2021 highs, according to local agents.

- In Lianyang, a downtown area popular with expats and financiers in Shanghai, residential prices have slid 15% to 20% from record highs in mid-2021.

Even as of March, before the latest property market crisis, more than half of tier-2 and tier-3 cities saw existing-home prices fall more than 15% from peaks, Guolian Securities economists wrote in a report citing data by existing housing transaction services provider KE Holdings Inc. Actual declines from peaks could be sharper, as the agency only compiles data starting November 2018, the economists cautioned

Top-tier cities, once considered resilient against a housing downturn, are also not immune. Prices of existing homes in at least five popular districts of Shenzhen have slumped 15% in the past three years, according to a July report by property research institute Leyoujia. The southern hub is the country’s least affordable housing market.

It’s hardly rocket science what is going on here: industry insiders and economists say China’s official home-price indexes are understating the depth of the downturn (by a lot) in part because of longstanding methodologies that struggle to capture market turning points, in part because – well – all of China’s data is propaganda.

That’s heightening concern among investors about the availability of timely economic data in China, where access to some information has become increasingly restricted under the government of President Xi Jinping. It also raises questions about whether policy makers themselves have an accurate understanding of the market as they devise measures to prop up demand. Another risk is that wary homebuyers stay on the sidelines, waiting for price declines to show up in the data before they step in.

Analysts say the methodology, which partly relies on surveys rather than price data from transactions, helps authorities to smooth the trend and to avoid large swings. By contrast, in the US, the widely cited S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller indexes use home-price data collected at local deed recording offices across the country.

For Henry Chin, who’s spent more than 20 years researching global real estate markets, the data’s source and accuracy are critical.

“Home-price data in many countries are based on total market transactions, yet China uses selective samples,” said Chin, the head of research for Asia Pacific at CBRE Group Inc. “When a market goes down, the true market condition is hard to be reflected in such data.”

China’s statistics bureau has said in an online explanation that raw data on new-home prices is based on all sales and purchases registered in local housing transaction bodies. Existing-home prices, though, are based on both sales of key projects and surveys, it said. The NBS uses the Laspeyres price index, a common formula used worldwide, to calculate its 70-city home-price gauge, the statistics bureau told Bloomberg. Market watchers say the methodology on sampling and index calculation remain ambiguous.

Survey-based data “serves a purpose avoiding extreme fluctuation,” said Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief Asia Pacific economist at Natixis SA in Hong Kong. “But when people are wary that prices are falling even more, thus not buying, such data defeats its own purpose.”

This partly explains why home price changes implied by official and private sources appear inconsistent with market perceptions on some occasions, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists said in a July report called “Understanding differences in China’s home price measures.”

Translation: nobody believes Chinese data any more.

Which is very bad for Beijing, since nobody will buy real estate – China’s biggest asset by orders of magnitude – if there is zero confidence in what the accurate price is, and until there is some comfort that the price drops are over.

What is worse is that even China’s state-owned property developers are now warning of widespread losses, fueling concerns that the housing crisis is expanding from the private sector to companies with government backing.

In a separate Bloomberg report, we learn that 18 out of 38 state-owned enterprise builders listed in Hong Kong and the mainland reported preliminary losses in the six months ended June 30, up from 11 that warned of full-year losses in 2022, according to a Bloomberg tally based on corporate filings. Two years ago, only four firms with controlling or major state shareholdings posted losses.

Some of the state-owned developers have cited declining profit margins and heavier provisions to write down asset values stemming from the housing woes. Companies seeing losses include some of the biggest developers owned by the central government. Shenzhen Overseas Chinese Town warned of a loss of as much as 1.7 billion yuan ($233 million), partly due to a marketing strategy to speed up home sales. That followed a loss in the second half of last year, which was its first since its 1997 listing.

Players in economically stronger cities are also suffering. Everbright Jiabao Co., operated by a local state asset manager in Shanghai’s Jiading district, said it expects its first ever half-year loss since its listing.

The warnings signal state builders are no longer immune from the two-year housing slump that has weakened the economy and triggered dozens of defaults by private peers, with speculation that Country Garden Holdings may be next, a collapse which would be more devastating than the Evergrande collapse two years ago. Authorities have in recent weeks stepped up pledges to support the property sector, though analysts are skeptical that the measures will be enough to revive the market anytime soon.

“China’s property slowdown is already hurting all developers, including the large government-linked ones,” said Zerlina Zeng, senior credit analyst at CreditSights Singapore. “We do not expect the situation to materially improve in the second half.”

That said, according to Bloomberg Intelligence credit analyst Andrew Chan, the loss warnings aren’t necessarily all doom and gloom for state developers – it’s natural that they would write down their inventories to reflect the slump in values, he notes.

“SOEs could be kitchen-sinking their results for better years ahead,” Chan said. “The key is whether they can still receive liquidity support from banks. For smaller SOE developers, it will be a case-by-case situation.”

But losses will reduce their scope to take on unfinished projects left by defaulted private-sector firms, further denting homebuyer sentiment. Chinese regulators see asset sales as a key step to easing the debt crisis, as President Xi Jinping’s government largely steers clear of direct bailouts.

“Sector consolidation anyhow takes time,” CreditSights’ Zeng said. “Especially in a property downturn when acquirers, such as SOEs and asset management firms, are demanding better valuations and sellers are not willing to dispose at a deep discount.”

One policy tool being used to revive the housing market and the broader economy is interest-rate cuts. In a surprise move, the People’s Bank of China on Tuesday made the steepest cut in three years on the rate on its one-year loans. The central bank has also encouraged lenders to lower mortgage rates, Jingyang Chen, Asia FX strategist at HSBC Holdings Plc, said earlier this month.

As of June, 100 out of 343 Chinese cities have lowered the rate floor of new-home mortgages or removed the minimum required, the PBOC said in its quarterly monetary policy report on Thursday. That has brought the nation’s average mortgage rate to 4.11% in June, down 0.51 percentage point from a year earlier.

Loading…