By Ye Xie, Bloomberg markets live reporter and strategist

This year marks another turbulent period for Chinese markets. It also highlights a striking feature: Chinese stocks are more isolated from the rest of the world than they’ve been for more than two decades.

For some investors, that underscores the diversification benefit of investing in China. For others, the unique risks strengthen the argument for carving out China from the rest of emerging markets.

Even with a rally over the past month, Chinese stocks remain among global underperformers this year. The MSCI China Index has lost 26%, compared with a decline of 19% of the MSCI all-country index.

Plus, volatility has been high throughout the year, punctuated by the Shanghai lockdown, tension around Taiwan and skepticism toward China’s new leadership following the Party Congress. Adding to these local market drivers, China is the only major economy that lowered borrowing costs.

With these idiosyncratic risks, it’s not surprising that the Chinese markets are increasingly out of sync with the rest of the world. The annual correlation between the MSCI China Index and MSCI’s global benchmark has dropped to 0.22, a level last seen in 2001 when China joined the World Trade Organization. In the bond market, 10-year bond government yields rose only 12 basis points, while US Treasury notes with same maturity jumped more than 200 basis points.

The low correlation has long been seen as one of the attractiveness for investing in China. On the flip side, it also strengthens the case to treat China as a standalone asset class.

Since the US-China trade war in 2018, the chorus for separating China from the rest emerging markets has grown louder. For starters, China, was simply too big. Even with the decline in recent years, China still accounts for about 30% of the MSCI emerging markets index. Secondly, some investors already have exposure through dedicated China funds. With China as a big chunk of the emerging market index, investors may have exposed to the country more than they want.

More importantly, Beijing is seeking to reduce its reliance on foreign countries in strategic industries, such as semiconductors, and in capital markets amid the tension with the West. That means China’s industrial, monetary and fiscal policy cycles may be different from the others.

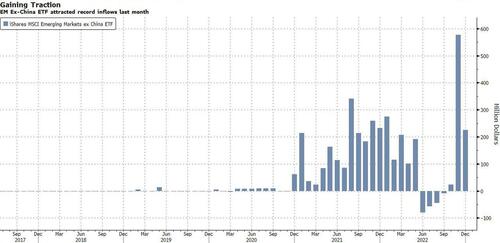

That separation trend is already clear. The iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ex China ETF attracted a record $577 million in November, one month after President Xi Jinping installed his allies in the leadership at the Party Congress. Until 2021, the fund was struggling attracting investors.

Next year, China is expected to be the only major economy to see its growth pick up. If materialized, it will again showcase the need to invest China differently.

By Ye Xie, Bloomberg markets live reporter and strategist

This year marks another turbulent period for Chinese markets. It also highlights a striking feature: Chinese stocks are more isolated from the rest of the world than they’ve been for more than two decades.

For some investors, that underscores the diversification benefit of investing in China. For others, the unique risks strengthen the argument for carving out China from the rest of emerging markets.

Even with a rally over the past month, Chinese stocks remain among global underperformers this year. The MSCI China Index has lost 26%, compared with a decline of 19% of the MSCI all-country index.

Plus, volatility has been high throughout the year, punctuated by the Shanghai lockdown, tension around Taiwan and skepticism toward China’s new leadership following the Party Congress. Adding to these local market drivers, China is the only major economy that lowered borrowing costs.

With these idiosyncratic risks, it’s not surprising that the Chinese markets are increasingly out of sync with the rest of the world. The annual correlation between the MSCI China Index and MSCI’s global benchmark has dropped to 0.22, a level last seen in 2001 when China joined the World Trade Organization. In the bond market, 10-year bond government yields rose only 12 basis points, while US Treasury notes with same maturity jumped more than 200 basis points.

The low correlation has long been seen as one of the attractiveness for investing in China. On the flip side, it also strengthens the case to treat China as a standalone asset class.

Since the US-China trade war in 2018, the chorus for separating China from the rest emerging markets has grown louder. For starters, China, was simply too big. Even with the decline in recent years, China still accounts for about 30% of the MSCI emerging markets index. Secondly, some investors already have exposure through dedicated China funds. With China as a big chunk of the emerging market index, investors may have exposed to the country more than they want.

More importantly, Beijing is seeking to reduce its reliance on foreign countries in strategic industries, such as semiconductors, and in capital markets amid the tension with the West. That means China’s industrial, monetary and fiscal policy cycles may be different from the others.

That separation trend is already clear. The iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ex China ETF attracted a record $577 million in November, one month after President Xi Jinping installed his allies in the leadership at the Party Congress. Until 2021, the fund was struggling attracting investors.

Next year, China is expected to be the only major economy to see its growth pick up. If materialized, it will again showcase the need to invest China differently.

Loading…