Authroed by Jonathan Harman & Lillian Ellis via RealClearDefense,

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has long sought to make geopolitical competitors dependent on it for materials necessary for national security by oversaturating the market with cheap Chinese products. Using that same strategy, the PRC is now looking to gain a monopoly on legacy chips—less advanced microchips required for both civilian and military technology. To combat this and future Chinese market threats to American national security, Congress should reinstate and modernize Section 421 of the 1974 Trade Act to allow the federal government to evaluate and recommend tariffs to the President for specific Chinese imports.

The PRC has long achieved dominance in international markets by subsidizing strategic industries to overproduce and flood the market with cheap products. Take rare earths as an example. Beginning in the 1980s, cheap Chinese labor and production costs drove out nearly all competing rare earth mines in the United States and abroad. Chinese rare earths now comprise nearly 80 percent of U.S. rare earth imports.

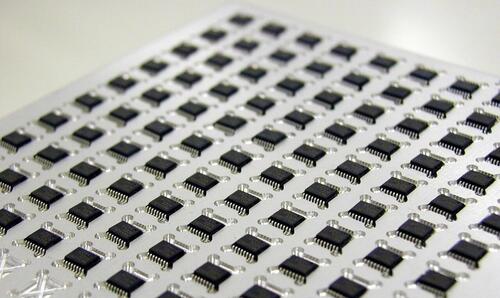

While China struggles to produce advanced chips that companies like TSMC in Taiwan manufactures, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) hopes to eventually dominate low-end legacy chip production—chips that are used in everything from everyday appliances to military technology.

The PRC’s “Made in China 2025” plan, created in 2015, continues to use government subsidies to fund production in strategic industries, like legacy chips, beyond market demand while exporting them at much cheaper prices—with hopes that these market distortions will help realize “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

With the world’s largest capacity for legacy chip production, China’s plan is on track to succeed. In the first quarter of 2024, Chinese legacy chip manufacturing increased by 40 percent and is set to account for 33 percent of the global market by 2027. That figure, according to U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, will likely grow to 60 percent over the next few years.

China gaining dominance in legacy chip manufacturing poses risks to U.S. national security as it creates critical vulnerabilities in U.S. defense industry supply chains. Legacy chips, while rudimentary, are necessary for everything from cars to F-35 fighter jets.

While the U.S. government has taken steps to prevent the PRC from obtaining the tools to produce more advanced chips through the CHIPS Act, it has not addressed Chinese legacy chip production. One way the federal government can curb China’s progress in this industry is by reinstating and modernizing Section 421.

Congress added Section 421 to the US-China Relations Act of 2000—the act that normalized trade with China as it entered the World Trade Organization (WTO)—to establish a “safeguard” against potential disruptions to U.S. producers. This safeguard, which expired in 2013, allowed the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) to determine whether specific imports from China posed a significant threat to U.S. domestic industry and recommend tariffs for the President to implement.

Section 421’s definition of a “threat” is intentionally broad, stating that if a Chinese product is imported into the U.S. “under such conditions as to cause or threaten to cause market disruption to the domestic producers of a like or directly competitive product, the President shall … proclaim increased duties or other import restrictions.” The case for Chinese legacy chips easily satisfies these requirements.

Imposing sanctions does not come without costs. In 2009, President Obama implemented Section 421 on Chinese tire imports—the only time a President has implemented Section 421 recommendations. These tariffs, while successfully reducing Chinese tire imports by 30 percent, led to higher costs for U.S. consumers while companies sourced tires from other global suppliers.

However, because microchips play such a critical role in U.S. national security, the benefits of Section 421 far outweigh the usual drawbacks of protectionist policy. Indeed, because China’s share of global microchip production is still in its infancy, it is in America’s interest to decouple sooner rather than later. As Liza Tobin, Senior Director for Economy at the Special Competitive Studies Project, noted at the Global Taiwan Institute’s 2023 Symposium: “We in the West have learned the hard way that efficiency maximization shouldn't be the only criteria that determines our trade and investment decisions.”

While testifying before Congress, Scott Paul, president of Alliance for American Manufacturing recommended reviving Section 421, saying “it would be a smart move by congress.”

Support for Section 421 is bipartisan. Last December, the Select Committee on the CCP released a joint report that recommended restoring Section 421 given its PRC-specific safeguards, explaining that the section does not require the explicit evidence of an unfair trade practice. As ranking member Representative Krishnamoorthi (D-IL) stated, in reference to Section 421: “It’s a trade tool that allows us to impose targeted, quicker counter measures against CCP market disruptions … it is time to revive and modernize Section 421.”

To ensure that a restored Section 421 is successful, it should be coupled with policies that promote domestic industry. As Riley Walters, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, said in an email on July 19th, tariffs are generally “a bit of a vicious cycle unless the root of the problem (Chinese overproduction) is addressed.” In the case of legacy chips, Section 421 tariffs could work in tandem with the $2 billion set aside in the CHIPS Act to build up domestic legacy chip manufacturing.

To get around Section 421 tariffs, the PRC could still produce Chinese-made chips elsewhere—a problem the Biden Administration had to resolve after implementing the CHIPS Act. To ensure tariffs are effective, a modernized Section 421 will likewise need to address these potential loopholes.

While politicians and experts should cautiously proceed with implementing any sort of protectionist policy, a modernized Section 421 would present a unique mechanism for securing America’s supply chains while promoting U.S. producers. The federal government should take these steps now to prevent the U.S. from becoming dependent on its greatest geopolitical rival for legacy chips as well as other products necessary for national security in the future.

Jonathan Harman is a Summer Fellow at the Global Taiwan Institute and student at Brigham Young University. He was previously an intern at the Heritage Foundation’s Center for National Defense.

Lillian Ellis is an intern at the Global Taiwan Institute. She is a recent graduate from Scripps College, where she majored in Politics and minored in Chinese. She has previously worked as a campaign manager in Washington state and as an intern for The Borgen Project.

Authroed by Jonathan Harman & Lillian Ellis via RealClearDefense,

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) has long sought to make geopolitical competitors dependent on it for materials necessary for national security by oversaturating the market with cheap Chinese products. Using that same strategy, the PRC is now looking to gain a monopoly on legacy chips—less advanced microchips required for both civilian and military technology. To combat this and future Chinese market threats to American national security, Congress should reinstate and modernize Section 421 of the 1974 Trade Act to allow the federal government to evaluate and recommend tariffs to the President for specific Chinese imports.

The PRC has long achieved dominance in international markets by subsidizing strategic industries to overproduce and flood the market with cheap products. Take rare earths as an example. Beginning in the 1980s, cheap Chinese labor and production costs drove out nearly all competing rare earth mines in the United States and abroad. Chinese rare earths now comprise nearly 80 percent of U.S. rare earth imports.

While China struggles to produce advanced chips that companies like TSMC in Taiwan manufactures, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) hopes to eventually dominate low-end legacy chip production—chips that are used in everything from everyday appliances to military technology.

The PRC’s “Made in China 2025” plan, created in 2015, continues to use government subsidies to fund production in strategic industries, like legacy chips, beyond market demand while exporting them at much cheaper prices—with hopes that these market distortions will help realize “the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

With the world’s largest capacity for legacy chip production, China’s plan is on track to succeed. In the first quarter of 2024, Chinese legacy chip manufacturing increased by 40 percent and is set to account for 33 percent of the global market by 2027. That figure, according to U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, will likely grow to 60 percent over the next few years.

China gaining dominance in legacy chip manufacturing poses risks to U.S. national security as it creates critical vulnerabilities in U.S. defense industry supply chains. Legacy chips, while rudimentary, are necessary for everything from cars to F-35 fighter jets.

While the U.S. government has taken steps to prevent the PRC from obtaining the tools to produce more advanced chips through the CHIPS Act, it has not addressed Chinese legacy chip production. One way the federal government can curb China’s progress in this industry is by reinstating and modernizing Section 421.

Congress added Section 421 to the US-China Relations Act of 2000—the act that normalized trade with China as it entered the World Trade Organization (WTO)—to establish a “safeguard” against potential disruptions to U.S. producers. This safeguard, which expired in 2013, allowed the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) to determine whether specific imports from China posed a significant threat to U.S. domestic industry and recommend tariffs for the President to implement.

Section 421’s definition of a “threat” is intentionally broad, stating that if a Chinese product is imported into the U.S. “under such conditions as to cause or threaten to cause market disruption to the domestic producers of a like or directly competitive product, the President shall … proclaim increased duties or other import restrictions.” The case for Chinese legacy chips easily satisfies these requirements.

Imposing sanctions does not come without costs. In 2009, President Obama implemented Section 421 on Chinese tire imports—the only time a President has implemented Section 421 recommendations. These tariffs, while successfully reducing Chinese tire imports by 30 percent, led to higher costs for U.S. consumers while companies sourced tires from other global suppliers.

However, because microchips play such a critical role in U.S. national security, the benefits of Section 421 far outweigh the usual drawbacks of protectionist policy. Indeed, because China’s share of global microchip production is still in its infancy, it is in America’s interest to decouple sooner rather than later. As Liza Tobin, Senior Director for Economy at the Special Competitive Studies Project, noted at the Global Taiwan Institute’s 2023 Symposium: “We in the West have learned the hard way that efficiency maximization shouldn’t be the only criteria that determines our trade and investment decisions.”

While testifying before Congress, Scott Paul, president of Alliance for American Manufacturing recommended reviving Section 421, saying “it would be a smart move by congress.”

Support for Section 421 is bipartisan. Last December, the Select Committee on the CCP released a joint report that recommended restoring Section 421 given its PRC-specific safeguards, explaining that the section does not require the explicit evidence of an unfair trade practice. As ranking member Representative Krishnamoorthi (D-IL) stated, in reference to Section 421: “It’s a trade tool that allows us to impose targeted, quicker counter measures against CCP market disruptions … it is time to revive and modernize Section 421.”

To ensure that a restored Section 421 is successful, it should be coupled with policies that promote domestic industry. As Riley Walters, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, said in an email on July 19th, tariffs are generally “a bit of a vicious cycle unless the root of the problem (Chinese overproduction) is addressed.” In the case of legacy chips, Section 421 tariffs could work in tandem with the $2 billion set aside in the CHIPS Act to build up domestic legacy chip manufacturing.

To get around Section 421 tariffs, the PRC could still produce Chinese-made chips elsewhere—a problem the Biden Administration had to resolve after implementing the CHIPS Act. To ensure tariffs are effective, a modernized Section 421 will likewise need to address these potential loopholes.

While politicians and experts should cautiously proceed with implementing any sort of protectionist policy, a modernized Section 421 would present a unique mechanism for securing America’s supply chains while promoting U.S. producers. The federal government should take these steps now to prevent the U.S. from becoming dependent on its greatest geopolitical rival for legacy chips as well as other products necessary for national security in the future.

Jonathan Harman is a Summer Fellow at the Global Taiwan Institute and student at Brigham Young University. He was previously an intern at the Heritage Foundation’s Center for National Defense.

Lillian Ellis is an intern at the Global Taiwan Institute. She is a recent graduate from Scripps College, where she majored in Politics and minored in Chinese. She has previously worked as a campaign manager in Washington state and as an intern for The Borgen Project.

Loading…