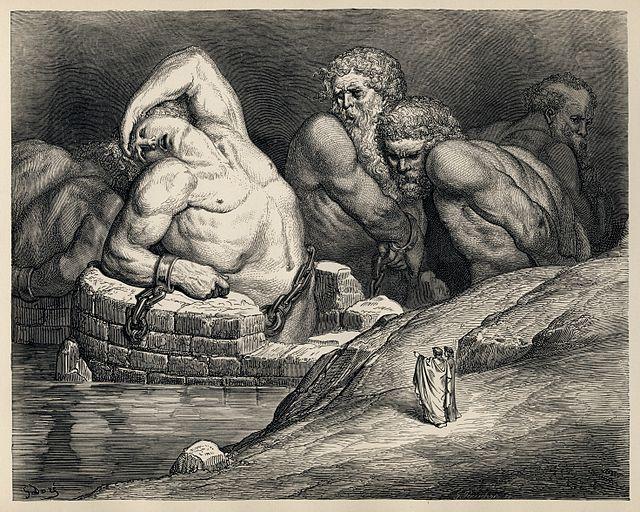

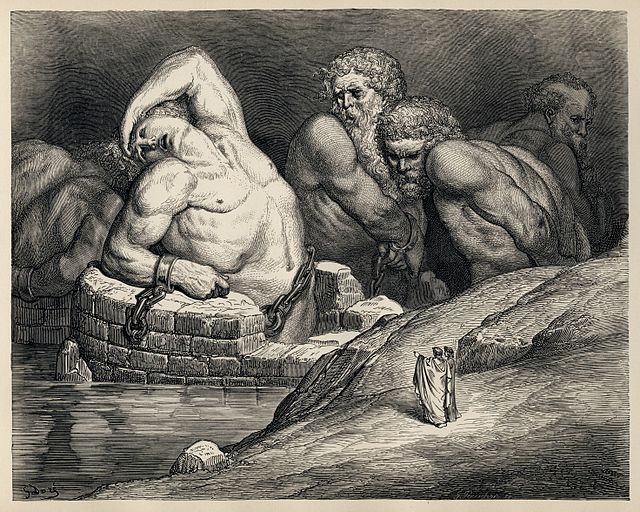

Photo Credit:Gustave Doré (1832 – 1883), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

An apropos fate for political treason.At that I turned, and saw before my feet

a lake of ice, which in the terrible cold

looked not like frozen water, but like glass.

— Inferno Canto 32. 22–24 (translated by Anthony Esolen)

In Dante’s Inferno, the relatively grievous nine circles of hell are chiefly populated by elite persona, sorry individuals from the author’s own deeply wronged past. Yet, Dante’s dead are quite familiar in their moral depravity and betrayal to the living, hellish versions at our society’s obscured helm, thriving in the shadows even today.

The famously principled and genuinely independent Hillsdale College offers an on-line completion certificate in Dante’s Divine Comedy. I took the course a few years ago to refresh my earlier study of Dante. An introduction to the Inferno via Hillsdale’s articulate treatment finely benchmarks the current relevance of Dante’s epic:

Dante’s Divine Comedy provides a grand education in the proper order of the human soul and the order of the cosmos. Through his account of the afterlife, Dante reveals universal truths about character and choice, the nature of God and man, and the path to freedom and happiness.

The Divine Comedy begins on Good Friday with Dante lost in a dark wood. Unable to save himself, Dante is rescued by the poet Virgil and begins his education by encountering the hopeless souls of the Inferno.

As Dante descends into the Inferno, he discovers the true state of his own heart through the people he meets. In order to return to the path of the ‘straight and true,’ Dante must properly order his desires for classical wisdom, love, politics, and the intellectual life.

Dante is engaged in the Inferno with a cosmic poetic recreation of the wages of corruption in the human heart. He most frequently attacks early 14th century legal and political figures, often identifying each by their treachery when alive.

Redemption is not at hand for those caught up in the Inferno—that is reserved for the latter two salvation books of the Divine Comedy epic. In Hell, there is no light, no warmth, and no love, and certainly no reparations on Satan’s behalf. There is, however, the slimmest possibility of human redemption, but only by a far distanced and desperately hoped for Divinity:

Dante moves through the Inferno in downward circles, not in a straight line. Thus, while his character seems to engage in the same kinds of behavior, he is making progress and improving.

Here in the final circle of hell, all is ice: the ice is strong enough to withstand a stone mountain falling against it, with a wind of icy air from Satan’s wings beating back and forth. Here, Dante will be unable to fully express what he experienced, but he and Virgil will discover a path forward.

Why does Dante consider treason to be the worst of sins, couched in the darkest place and with the worst of sinners, in the ninth Circle of Hell?

Readers and scholars credit Dante’s classical education, and his personal, professional, and political history in youth and early middle age as eventual inspiration for the Divine Comedy. Its epic theology is notably influenced by traditional Catholic and Jewish spiritual mysticism, and calls for punishment for sin and the hope of a redemptive forgiveness—but only and lastly via divine intervention.

Dante’s precipitous and engineered political fall in his middle age is well documented:

When word of the political overthrow in Florence had reached the Pontiff, Boniface allowed most members of the group to return home, but refused to grant Dante permission to leave Rome. Consequently, Dante was unable to return to Florence to defend himself against corruption charges levied against him by the ruling Neri faction. On January 27, 1302, he was sentenced to two years of exile from the city. On March 10 a new decree was issued and Dante was forever forbidden to return to the city on pain of death. Dante never saw his beloved Florence again.

Why should we, in 2025 with this great political and cultural chaos at our heels, concern ourselves with the 14th century and the ninth Circle of Hell? Because Dante speaks so eloquently and with such understanding, of treason—pointedly, political treason—as the greatest, most damning human sin and disorder. We’ve got that now, in spades.

To begin his Inferno journey, Dante meets up with his ancient mentor, the beloved Roman poet-philosopher Virgil, a model of probity and virtue. With Virgil’s assistance and humor, the two start their long troop into the far reaches of Hell. Virgil guides Dante in a circular descent that paradoxically results in a journey back upward-toward a glorified, eternal liberation from all forms of corruption and deviance.

But before Dante can rise up to heaven, Satan is the last in creation that he must finally confront, the Evil One who, with unspeakable malice, is locked in ice and bound in chains, glaring from the bottom of Hell’s deepest pit. It is the author’s ultimately terrible confrontation with the Devil that sparks a total rejection of evil, and a reversal (however minutely gained) of Dante’s voyage. Dante carries himself eventually back up to “see the stars,” almost unreachable above a view of high crags yet to climb.

Dante is released from his visit to Hell and its denizens. He is on his new way to an eventual reunion, now with Virgil’s departure but with his luminous Beatrice’s stern but abstracted entrance—to goodness, light, and to God’s love.

Dante’s circles are—in ascending order of severity, lust, gluttony, greed, wrath, heresy, violence, fraud, and—finally, most critically, treachery/treason. When within the final, Ninth Circle of Hell, Dante had found himself deprived of everything and anything of worth. Of all the nine allegories of human error and sin, starting with the most mild and descending to the most irreparable sinning: treason is the ticket.

Dante makes no bones, often and by naming names, in claiming eternal destruction for those who commit treasonous, or treacherous, acts against others. To Dante, politics is intimately tied to morality—or not—and relates directly to the certain ends of our bodies and souls.

Satan is, there in his Ninth Circle, the original treasonous being, the angel Lucifer fallen, the majordomo of treasonous ways and acts.

All of the great world religions have pledged some version of fealty to God(s) and/or Demon(s). Have they all been entirely wrong? Of course not. Of all, the Holy Bible is the most widely read, believed, and morally exquisite work in literary history. Its proven, factual recording of the human capacity for good or evil lays sure claims on the afterlife. But where eternity’s spent is up to—you guessed it—every human soul.

That’s pure Dante. His poetry warns us that treasonous political acts committed on earth provide a richly seductive yet very temporal cover for the kind of thinking and actions that will send the soul downward to reach the Ninth Circle of eternal doom.

Victoria White Berger earned her dual B.A. in English and History from Duke University and her M.A. in Philosophy from the University of Missouri at St. Louis. Her Master of Philosophy thesis, “Cause and Reason in Intentional Action” is widely read internationally. Her writing can be found at American Thinker, The American Spectator, Louisiana’s Dead Pelican, and on her Substack account: https://victoriawhiteberger.substack.com/.

<img alt="Gustave Doré (1832 – 1883), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons" captext="Wikimedia Commons” src=”https://conservativenewsbriefing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/dante-meets-satan-in-the-inferno-the-ninth-circle-of-hell.jpg”>

Image: Public domain.