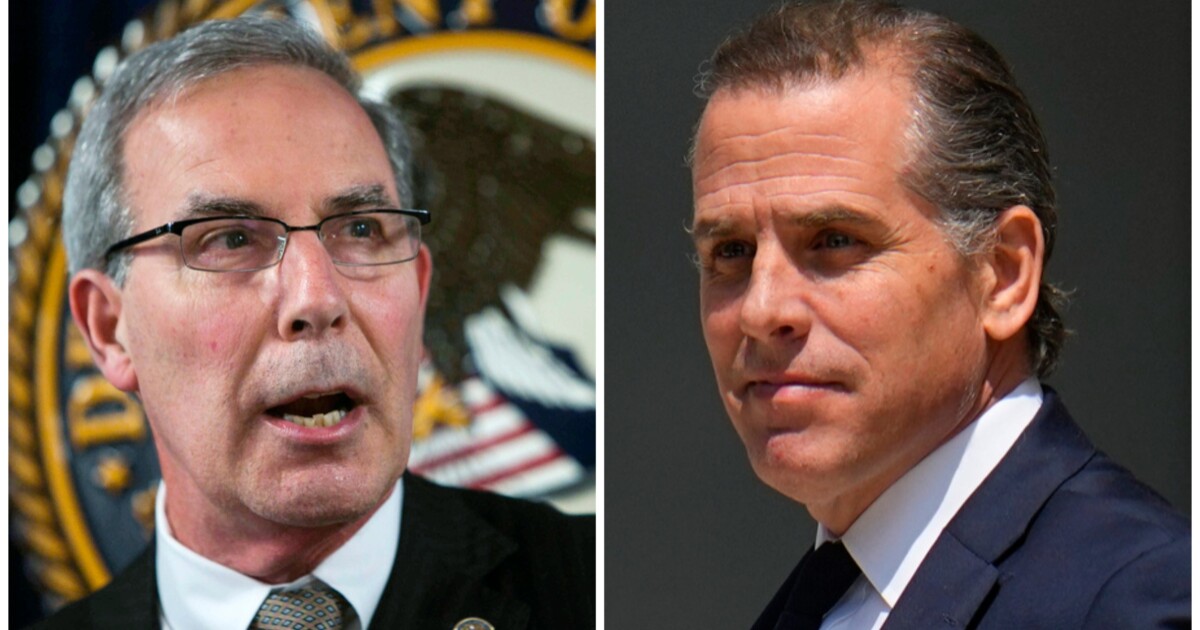

EXCLUSIVE — David Weiss wanted to bring charges against Hunter Biden in Washington, D.C., the district’s federal prosecutor told Congress in new testimony, lending credence to whistleblower claims of preferential treatment for President Joe Biden‘s son.

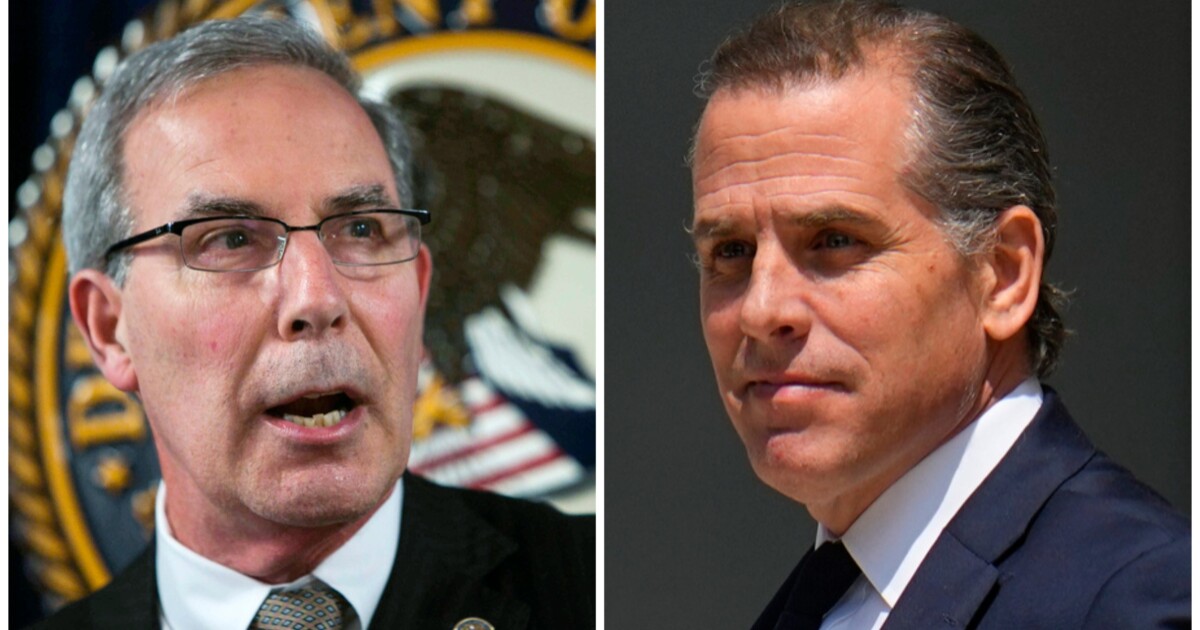

U.S. Attorney Matthew Graves said during a closed-door interview last week with the House Judiciary Committee that Weiss, then a U.S. attorney for Delaware, called Graves about the case at the end of February or beginning of March of 2022.

MCCARTHY KEEPS DOOR OPEN TO RETURN AS SPEAKER: ‘WHATEVER THE CONFERENCE WANTS, I WILL DO’

“Mr. Weiss said that he had an investigation that he had been conducting. Some of the charges related to that investigation needed to be venued out of the district, and he described the logistical support that he needed,” Graves said, according to a 180-page transcript of the interview reviewed by the Washington Examiner.

Graves indicated the logistical support Weiss referenced on the call would have included Graves arranging a grand jury in Washington on behalf of Weiss.

The phone call lasted about 10 minutes and was the only time Graves spoke directly to Weiss about the Hunter Biden case, he said.

Graves also addressed the perception that he “blocked” or “refused to” partner with Weiss on the case, an idea that formed after two whistleblowers and other IRS and FBI witnesses accused Graves of declining to partner with Weiss. The accusation prompted questions about why charges were never brought in Washington and if Graves had hampered Weiss’s case.

Graves said he recalled asking Weiss on the phone call “whether he was just looking for the kind of normal administrative support that any U.S. attorney would need if they were going to come and bring a case in another jurisdiction … or whether he was asking for us to join the investigation.”

Weiss responded that he was looking for Graves’s office to provide support “at a minimum” but that they could “discuss further joining or not,” Graves said.

Graves then met with the head of the criminal division in the Washington office and instructed him to have staffers seek a briefing from the Delaware office, which was running the Hunter Biden case, and to get back to Graves with a recommendation on whether to partner with Weiss on the case.

After they received a briefing, Graves then met with five or six members of his staff on or about March 19, 2022, to decide how to proceed, he said.

A committee aide asked Graves, “And the decision was made not to move forward with the case, correct?”

Graves said, “So I think what was obviously publicly reported and is known — and I’m trying to be careful, given that there’s an ongoing investigation — is that we ultimately did not join.”

Graves highlighted that he, not Weiss, was the first person to raise the option of partnering with Weiss on the case and then detailed how that was a “rare hybrid model” of addressing venue matters. That approach was “exceedingly rare,” Graves said.

“The challenge is — particularly when you’re talking about U.S. attorney and U.S. attorney — is you’re bringing in another chain of command. And once you’re partnered, you have to reach a consensus,” Graves said. “So, as a manager, in general, we don’t want to do that.”

He added, “You’re kind of buying a mansion without an inspection, and whatever problems exist, you are buying those.”

Graves said that in normal circumstances, his office would either take over the case or prosecutors would be granted special attorney status so that they could work within the Washington jurisdiction.

Graves only entertained the rare “hybrid” option of working with Weiss on the case in a joint manner because, he said, the white-collar nature of the alleged crimes at hand were prone to extensive litigation that “might create binding precedent in our jurisdiction.”

Graves’s comments run contrary to Weiss’s remarks in a June 30 letter to House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan (R-OH) in which he said, “Common Departmental practice is to contact the United States Attorney’s Office for the district in question and determine whether it wants to partner on the case.”

Graves was also adamant that he conveyed to Weiss his willingness to provide the “logistical support” Weiss needed to bring charges in Washington despite his later decision not to go as far as to join him on the case.

Almost all of Graves’s involvement, from the phone call with Weiss to the meeting with his criminal division chief and the March 19 meeting in which his office decided not to partner with Weiss, spanned about three weeks.

Graves repeatedly noted that he had to move fast during that time frame, saying he had tasked his criminal division chief with “immediately taking steps” to provide support and asked him to assign staff to do a “quick assessment because time was of the essence, and we had to make a decision quickly.”

That aligns with allegations about timing problems made by the two whistleblowers, both veteran IRS criminal investigators involved in the case. They said they became frustrated in 2022 that the statute of limitations would eventually expire for charges for 2014 and 2015, thereby “sanitiz[ing] the most substantive criminal conduct” of the case.

Asked if Graves had any follow-up interactions with his staff after March 19 to make sure Weiss knew he had a “green light” to work in Washington and that Graves would help with any logistics Weiss needed, Graves replied that he had “a conversation or two along those lines” around the April or May time frame.

“I can’t really get into the specifics of the conversation,” he said.

When pressed on the matter, he said, “I could just say at a high level, they alerted me to something about the status of Delaware’s investigation.”

Graves, who was accompanied by two DOJ lawyers at the interview, repeatedly declined to provide details about the case, citing that those details were outside the agreed-upon scope of his interview with the committee and would threaten the integrity of the prosecution.

Graves also refused to provide the names of the people at the March 19 meeting, resulting in a tense exchange at one point with a GOP committee aide.

Graves said that given the understanding that the transcript of the interview could leak, he did not want the meeting attendees’ names to appear on it because of threats his staff had already received. The GOP aide then offered to go off the record, at which point Graves and a DOJ lawyer stood firm and said the committee could confer with the DOJ’s Office of Legislative Affairs to seek the names.

Weiss, who brought three felony gun charges against Hunter Biden last month over a 2018 gun incident, is also expected to bring charges against him for the 2017 and 2018 tax years, but it remains unclear why Weiss has not brought charges against the president’s son for prior years.

Attorney General Merrick Garland, who appointed Weiss as special counsel in August, was confronted by lawmakers in a hearing last month about the matter. Garland repeatedly deferred to Weiss and noted that as special counsel, he would be required to issue a publicly available report detailing his prosecutorial decisions in the case.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

A Judiciary Committee spokesperson declined to comment.

A spokesperson for Weiss’s office did not respond to a request for comment.