Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

I recently debated with Michael Pento, who made an interesting statement that increases in the money supply, the deficit, and a return to quantitative easing (QE) will lead to 1970s-style inflation. The recent experience of inflation in 2021 and 2022 would seem to justify such a view. However, is that historically the case, or was the recent inflationary surge due to a different set of drivers? In today’s post, we will examine the money supply represented by M2, the Federal budget deficit, the Fed’s previous adventures with QE, and the correlation to inflation.

Let’s begin with the money supply. One common mistake the “inflation is coming back” crowd makes is focusing on increases in the money supply. Their key argument is that the government is “printing money out of thin air, destroying the dollar’s value.” This argument has two fallacies.

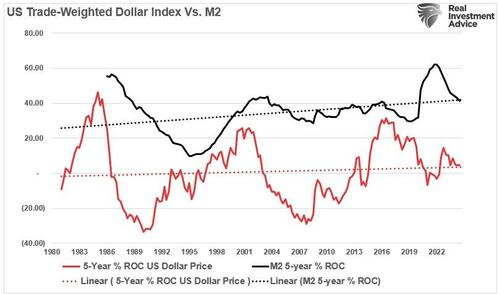

The first is to view the inflation-adjusted value of the dollar and claim it has less purchasing power today than in 1900. While this is a true statement, it assumes that the U.S. is the only country in the world that has experienced inflation over the last 125 years. In other words, the value of the U.S. dollar has declined relative to every other currency in the world as the money supply has grown. However, that has not been the case. The chart below shows the 5-year annual % change of the U.S. dollar on a trade-weighted basis versus the money supply. Today’s dollar has roughly the same value as in 1980, and the money supply has increased. Notably, increases in the money supply, on a rate of change basis, typically correlate to a stronger, not weaker, dollar.

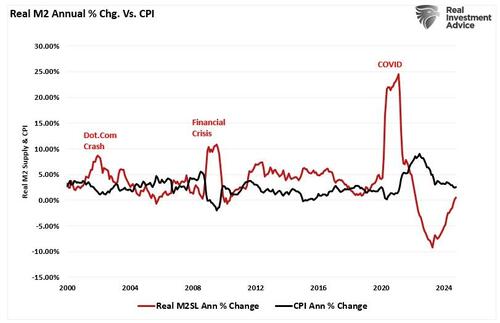

The second flaw is that increases in the money supply create inflation. Historically, money supply changes have not led to inflation increases, except for the COVID-19 pandemic, where the supply/demand balance was shifted. (We will discuss that in detail momentarily.) Outside of that singular and unique event, increases in the money supply have generally coincided with recessionary and deflationary events like the “Dot.com crash” and “Financial Crisis.” However, since the turn of the century, the inflation rate has remained fairly stable, averaging roughly 2.6%, with M2 growing at 3.8%. Most notably, from 2009 to 2019, the average inflation rate was below the long-term average despite increased money supply levels. In other words, the increased money supply did not lead to inflation.

While Michael argued during the debate that increased “money printing” would lead to higher inflation and interest rates, there is a reason that hasn’t occurred outside of the Pandemic shutdown. The reason is that the government is not “printing” money.

“All money is lent into existence.”

Read that again.

When the government needs to pay for obligations that exceed current revenues, the U.S. Treasury issues debt. That debt is sold to the primary dealers, who purchase it and provide capital for the Government to meet its obligations. If the Treasury Department could just “print” money, there would be no need to issue debt. This is why debt issuance has increased over the last four decades: to meet the continued shortfall between government spending and incoming revenue, known as the “federal deficit.”

The Federal Deficit Is Deflationary

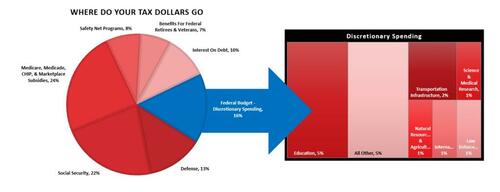

Michael’s second argument was that the deficit would lead to inflation and higher interest rates. This argument has several problems, but first, we must understand how the deficit is derived. Here is a current breakdown of the Federal budget and deficit spending requirements through the end of 2023 (the data for 2024 is not available at the time of this publication.)

According to the Center On Budget & Policy Priorities, in 2023, roughly 90% of every tax dollar went to non-productive spending.

“In fiscal year 2023, the federal government spent $6.1 trillion, amounting to 22.7 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). About nine-tenths of the total went toward federal programs; the remainder went toward interest payments on the federal debt. Of that $6.1 trillion, only $4.4 trillion was financed by federal revenues. The remaining amount was financed by borrowing.”

Think about that for a minute. In 2023, 90% of all expenditures went to social welfare, non-productive spending, and interest on the debt. Those payments required $6.1 trillion, roughly 138% more than the tax dollars collected.

The problem with “non-productive spending” is that it has a zero to negative multiplier on economic growth.

“History teaches us that although investments in productive capacity can in principle raise potential growth and r* in such a way that the debt incurred to finance fiscal stimulus is paid down over time (r-g<0), it turns out that there is little evidence that it has ever been achieved in the past.

Rising federal debt as a percentage of GDP has historically been associated with declines in estimates of r* – the need to save to service debt depresses potential growth. The broad point is that aggressive spending is necessary, but not sufficient. Spending must be designed to raise productive capacity, potential growth, and r*. Absent true investment, public spending can lower r*, passively tightening for a fixed monetary stance.” – Stuart Sparks, Deutsche Bank

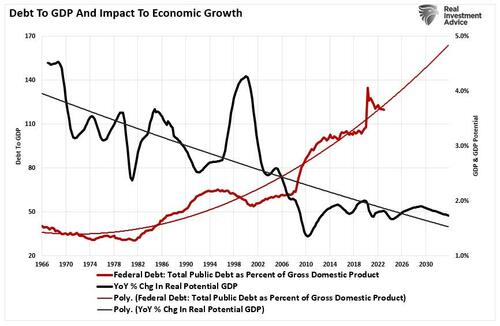

We can see this visually by comparing the Federal debt as a percentage of GDP to potential economic growth. Since government spending is primarily non-productive, it should be unsurprising that increases in debt do foster stronger economic activity.

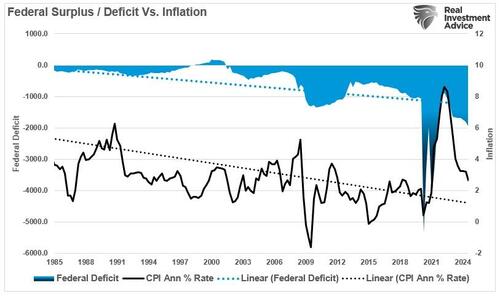

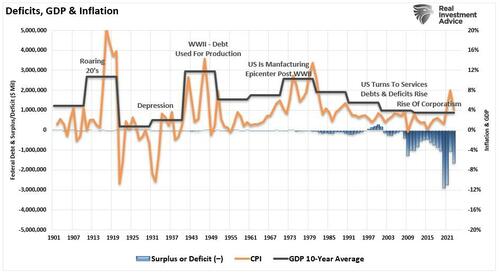

That last sentence is the most crucial. Inflation comes from increases in demand,d which is reflected by increases in economic activity. However, since 1985, the annual inflation rate has decreased while the Federal deficit has increased. What should be noted is that inflation tends to rise when the federal deficit declines. That correlation makes sense, as the deficit decreases when tax revenues increase due to more substantial economic growth rates.

However, when economic activity slows, the federal deficit must increase to offset the decline in tax revenues to meet the required government spending. As such, increases in the deficit are directly correlated to slowing economic activity and declining inflation.

The crucial conclusion is that today’s backdrop of higher inflation is radically different, unlike the 1970s, when inflation was a function of surging commodity prices due to the Iranian oil embargo. A reversal in demographic trends, elevated debt levels, and a shift from manufacturing to services suggest the long-term trend growth rate of the economy and inflation will be lower, and so will inflation.

But what about the Federal Reserve?

QE Doesn’t Create Inflation

Michael’s final argument was that the Federal Reserve “learned its lesson in 2020”.As such, the Fed would be reticent to do “Quantitative Easing (QE)” in the future due to inflation concerns. The Federal Reserve is well aware of what caused inflation in 2020 and that it wasn’t QE that caused it.

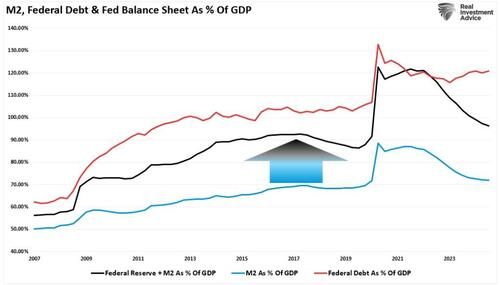

However, to understand why, we must return to how the Government funds its deficit. When the government issues debt, the major banks or “primary dealers” must buy that debt. If the Federal Reserve engages in a QE program, it issues a notice of what bonds it buys. The primary dealers can then submit those bonds to the Federal Reserve for a “credit” to their reserve account. This exchange DOES NOT increase the money supply; instead, it is an asset swap between the bank and the Fed. This is why M2 and debt are highly correlated when you look at them as a percentage of GDP. It would have been noticeable if the Federal Reserve had added to the money supply.

As noted above, “Money is lent into existence.”

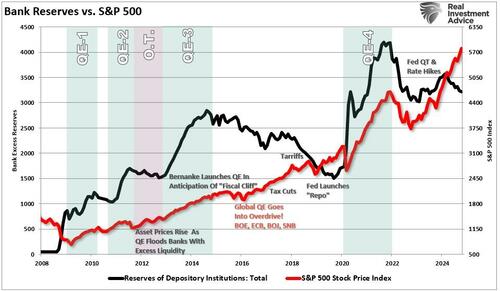

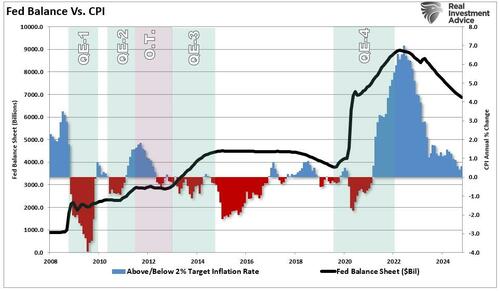

As such, an asset swap, in this case, a digital accounting mechanism, does not create money. However, it does boost reserves to the financial system, as shown below. While banks should lend those reserves to the economy, that has not happened. Instead, those reserves have found their way back into the financial markets.

However, increasing bank reserves is not inflationary, particularly when, as noted, those reserves are not lent to the economy to create activity. This is why, despite repeated rounds of QE, the annual inflation rate moderated around the Fed’s 2% target until early 2020.

Therefore, if QE does not create inflation by stimulating economic activity, why did inflation surge in 2020? For that answer, we must return to the very basic principles of economics.

Why We Had Inflation And Why It’s Not Coming Back

In economics, inflation is a general increase in the prices of goods and services. Changes in inflation are a function of fluctuations in actual demand for goods and services (also known as demand shocks, including changes in fiscal or monetary policy or recession), changes in available supplies such as during energy crises (also known as supply shocks), or changes in inflation expectations, which may be self-fulfilling. Note that supply and demand are key facets of the inflation equation.

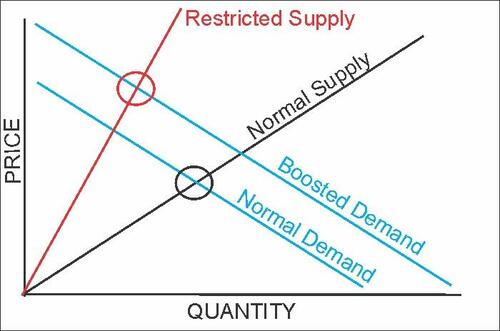

Basic economics states prices will be set at a level where the supply of goods or services meets consumer demand.

There was no better example of what happens with prices than the massive Government interventions in 2020 and 2021. During that period, the Government sent rounds of checks to households (creating demand) during an economic shutdown (shuttering supply). The economic illustration shows this basic principle taught in every “Econ 101” class. Unsurprisingly, in 2020, inflation was the consequence of restricting supply and massively increasing demand.

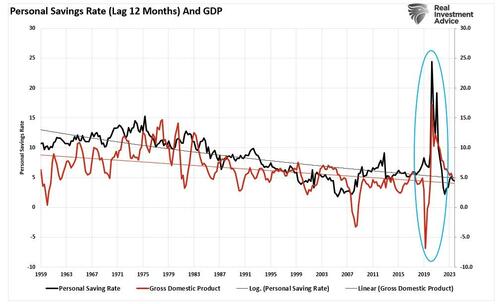

That massive surge in stimulus sent directly to households resulted in an unprecedented spike in “savings,” creating artificial demand. As shown, the “pig in the python” effect is evident. Over the next two years, that “bulge” of excess liquidity has reverted to the previous growth trend. Given that economic growth lags behind the reversion in savings by about 12 months, we should continue to see economic growth slow into 2025. Notably, that “lag effect” is critical to the “inflation is returning” thesis.

Understanding that inflation is solely a function of supply and demand, reversing monetary liquidity will erode future economic activity. Notably, what caused the inflation spike post-2020 was not an increase in the debt or the Federal Reserve but rather the temporary increase in the money supply caused by sending checks to households. Therefore, unless the Government passes a new infrastructure spending bill of massive proportions or sends another round of stimulus to households, no factor is available to restart the inflation process of increased demand.

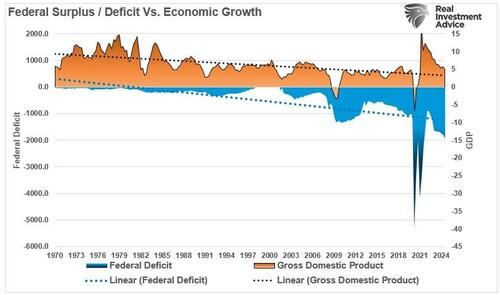

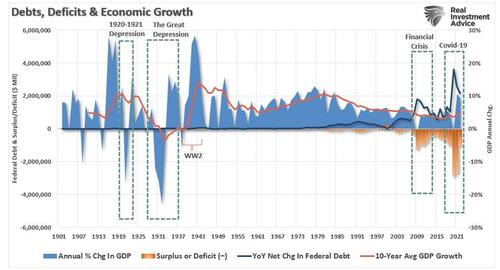

Over the coming decades, the massive surge in unproductive debt will increase deflationary pressures and slower economic growth. These issues are not new but have plagued economic growth for the last 40-years. The result is that debts and deficits will continue to detract from rather than contribute to economic growth. As shown, the surge in debt and deficits coincides with a peak in the 10-year average economic growth rate.

The decline in economic prosperity adds deflationary pressures on the economy. Such requires continued government deficit spending to sustain the demands on the welfare system.

The reality is that despite mainstream thinking that inflation will resurge due to rising debts, deficits, or Federal Reserve interventions, the historical evidence does not support such claims. The negative impact of debt on the economy is evident. Furthermore, the negative correlation between the size of the government and economic growth suggests the most likely outcome in the future is deflation.

Could something else happen? Absolutely. However, another inflationary surge will require an event that causes a massive distortion in supply and demand. Until such an imbalance occurs, the biggest risk for investors to focus on remains disinflation, which ultimately impacts earnings growth.

Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

I recently debated with Michael Pento, who made an interesting statement that increases in the money supply, the deficit, and a return to quantitative easing (QE) will lead to 1970s-style inflation. The recent experience of inflation in 2021 and 2022 would seem to justify such a view. However, is that historically the case, or was the recent inflationary surge due to a different set of drivers? In today’s post, we will examine the money supply represented by M2, the Federal budget deficit, the Fed’s previous adventures with QE, and the correlation to inflation.

Let’s begin with the money supply. One common mistake the “inflation is coming back” crowd makes is focusing on increases in the money supply. Their key argument is that the government is “printing money out of thin air, destroying the dollar’s value.” This argument has two fallacies.

The first is to view the inflation-adjusted value of the dollar and claim it has less purchasing power today than in 1900. While this is a true statement, it assumes that the U.S. is the only country in the world that has experienced inflation over the last 125 years. In other words, the value of the U.S. dollar has declined relative to every other currency in the world as the money supply has grown. However, that has not been the case. The chart below shows the 5-year annual % change of the U.S. dollar on a trade-weighted basis versus the money supply. Today’s dollar has roughly the same value as in 1980, and the money supply has increased. Notably, increases in the money supply, on a rate of change basis, typically correlate to a stronger, not weaker, dollar.

The second flaw is that increases in the money supply create inflation. Historically, money supply changes have not led to inflation increases, except for the COVID-19 pandemic, where the supply/demand balance was shifted. (We will discuss that in detail momentarily.) Outside of that singular and unique event, increases in the money supply have generally coincided with recessionary and deflationary events like the “Dot.com crash” and “Financial Crisis.” However, since the turn of the century, the inflation rate has remained fairly stable, averaging roughly 2.6%, with M2 growing at 3.8%. Most notably, from 2009 to 2019, the average inflation rate was below the long-term average despite increased money supply levels. In other words, the increased money supply did not lead to inflation.

While Michael argued during the debate that increased “money printing” would lead to higher inflation and interest rates, there is a reason that hasn’t occurred outside of the Pandemic shutdown. The reason is that the government is not “printing” money.

“All money is lent into existence.”

Read that again.

When the government needs to pay for obligations that exceed current revenues, the U.S. Treasury issues debt. That debt is sold to the primary dealers, who purchase it and provide capital for the Government to meet its obligations. If the Treasury Department could just “print” money, there would be no need to issue debt. This is why debt issuance has increased over the last four decades: to meet the continued shortfall between government spending and incoming revenue, known as the “federal deficit.”

The Federal Deficit Is Deflationary

Michael’s second argument was that the deficit would lead to inflation and higher interest rates. This argument has several problems, but first, we must understand how the deficit is derived. Here is a current breakdown of the Federal budget and deficit spending requirements through the end of 2023 (the data for 2024 is not available at the time of this publication.)

According to the Center On Budget & Policy Priorities, in 2023, roughly 90% of every tax dollar went to non-productive spending.

“In fiscal year 2023, the federal government spent $6.1 trillion, amounting to 22.7 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). About nine-tenths of the total went toward federal programs; the remainder went toward interest payments on the federal debt. Of that $6.1 trillion, only $4.4 trillion was financed by federal revenues. The remaining amount was financed by borrowing.”

Think about that for a minute. In 2023, 90% of all expenditures went to social welfare, non-productive spending, and interest on the debt. Those payments required $6.1 trillion, roughly 138% more than the tax dollars collected.

The problem with “non-productive spending” is that it has a zero to negative multiplier on economic growth.

“History teaches us that although investments in productive capacity can in principle raise potential growth and r* in such a way that the debt incurred to finance fiscal stimulus is paid down over time (r-g<0), it turns out that there is little evidence that it has ever been achieved in the past.

Rising federal debt as a percentage of GDP has historically been associated with declines in estimates of r* – the need to save to service debt depresses potential growth. The broad point is that aggressive spending is necessary, but not sufficient. Spending must be designed to raise productive capacity, potential growth, and r*. Absent true investment, public spending can lower r*, passively tightening for a fixed monetary stance.” – Stuart Sparks, Deutsche Bank

We can see this visually by comparing the Federal debt as a percentage of GDP to potential economic growth. Since government spending is primarily non-productive, it should be unsurprising that increases in debt do foster stronger economic activity.

That last sentence is the most crucial. Inflation comes from increases in demand,d which is reflected by increases in economic activity. However, since 1985, the annual inflation rate has decreased while the Federal deficit has increased. What should be noted is that inflation tends to rise when the federal deficit declines. That correlation makes sense, as the deficit decreases when tax revenues increase due to more substantial economic growth rates.

However, when economic activity slows, the federal deficit must increase to offset the decline in tax revenues to meet the required government spending. As such, increases in the deficit are directly correlated to slowing economic activity and declining inflation.

The crucial conclusion is that today’s backdrop of higher inflation is radically different, unlike the 1970s, when inflation was a function of surging commodity prices due to the Iranian oil embargo. A reversal in demographic trends, elevated debt levels, and a shift from manufacturing to services suggest the long-term trend growth rate of the economy and inflation will be lower, and so will inflation.

But what about the Federal Reserve?

QE Doesn’t Create Inflation

Michael’s final argument was that the Federal Reserve “learned its lesson in 2020”.As such, the Fed would be reticent to do “Quantitative Easing (QE)” in the future due to inflation concerns. The Federal Reserve is well aware of what caused inflation in 2020 and that it wasn’t QE that caused it.

However, to understand why, we must return to how the Government funds its deficit. When the government issues debt, the major banks or “primary dealers” must buy that debt. If the Federal Reserve engages in a QE program, it issues a notice of what bonds it buys. The primary dealers can then submit those bonds to the Federal Reserve for a “credit” to their reserve account. This exchange DOES NOT increase the money supply; instead, it is an asset swap between the bank and the Fed. This is why M2 and debt are highly correlated when you look at them as a percentage of GDP. It would have been noticeable if the Federal Reserve had added to the money supply.

As noted above, “Money is lent into existence.”

As such, an asset swap, in this case, a digital accounting mechanism, does not create money. However, it does boost reserves to the financial system, as shown below. While banks should lend those reserves to the economy, that has not happened. Instead, those reserves have found their way back into the financial markets.

However, increasing bank reserves is not inflationary, particularly when, as noted, those reserves are not lent to the economy to create activity. This is why, despite repeated rounds of QE, the annual inflation rate moderated around the Fed’s 2% target until early 2020.

Therefore, if QE does not create inflation by stimulating economic activity, why did inflation surge in 2020? For that answer, we must return to the very basic principles of economics.

Why We Had Inflation And Why It’s Not Coming Back

In economics, inflation is a general increase in the prices of goods and services. Changes in inflation are a function of fluctuations in actual demand for goods and services (also known as demand shocks, including changes in fiscal or monetary policy or recession), changes in available supplies such as during energy crises (also known as supply shocks), or changes in inflation expectations, which may be self-fulfilling. Note that supply and demand are key facets of the inflation equation.

Basic economics states prices will be set at a level where the supply of goods or services meets consumer demand.

There was no better example of what happens with prices than the massive Government interventions in 2020 and 2021. During that period, the Government sent rounds of checks to households (creating demand) during an economic shutdown (shuttering supply). The economic illustration shows this basic principle taught in every “Econ 101” class. Unsurprisingly, in 2020, inflation was the consequence of restricting supply and massively increasing demand.

That massive surge in stimulus sent directly to households resulted in an unprecedented spike in “savings,” creating artificial demand. As shown, the “pig in the python” effect is evident. Over the next two years, that “bulge” of excess liquidity has reverted to the previous growth trend. Given that economic growth lags behind the reversion in savings by about 12 months, we should continue to see economic growth slow into 2025. Notably, that “lag effect” is critical to the “inflation is returning” thesis.

Understanding that inflation is solely a function of supply and demand, reversing monetary liquidity will erode future economic activity. Notably, what caused the inflation spike post-2020 was not an increase in the debt or the Federal Reserve but rather the temporary increase in the money supply caused by sending checks to households. Therefore, unless the Government passes a new infrastructure spending bill of massive proportions or sends another round of stimulus to households, no factor is available to restart the inflation process of increased demand.

Over the coming decades, the massive surge in unproductive debt will increase deflationary pressures and slower economic growth. These issues are not new but have plagued economic growth for the last 40-years. The result is that debts and deficits will continue to detract from rather than contribute to economic growth. As shown, the surge in debt and deficits coincides with a peak in the 10-year average economic growth rate.

The decline in economic prosperity adds deflationary pressures on the economy. Such requires continued government deficit spending to sustain the demands on the welfare system.

The reality is that despite mainstream thinking that inflation will resurge due to rising debts, deficits, or Federal Reserve interventions, the historical evidence does not support such claims. The negative impact of debt on the economy is evident. Furthermore, the negative correlation between the size of the government and economic growth suggests the most likely outcome in the future is deflation.

Could something else happen? Absolutely. However, another inflationary surge will require an event that causes a massive distortion in supply and demand. Until such an imbalance occurs, the biggest risk for investors to focus on remains disinflation, which ultimately impacts earnings growth.

Loading…