Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

The Federal Reserve’s reverse repo (RRP) facility has been a key support for liquidity and stocks this year. But it is falling. As it approaches zero, markets face much less benign conditions as a formidable tailwind is extinguished.

Everyone’s a plumber, or at least should be.

Not in the sense that we all need to get handy with a spanner, but in that every investor should have at least a basic knowledge of financial plumbing in the modern central-banking regime.

A good place to start is the Fed’s RRP facility.

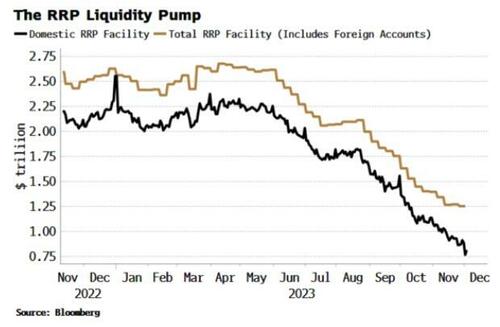

It reached a peak of over $2.5 trillion in May this year. That’s a lot of cash to have hidden down the sofa. But it is now falling at a steady rate, down more than half from its peak. What happens when it goes to zero is a key question for markets and plumbers alike.

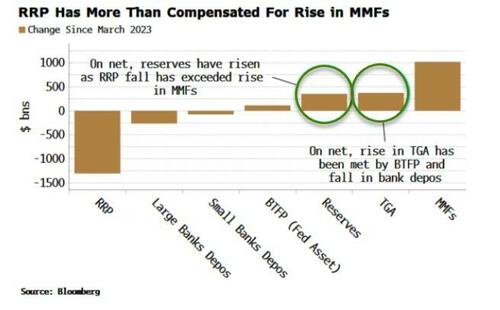

The RRP has been a veritable liquidity pump this year, acting as a source of stability for markets. Money that would otherwise have been taken out of the system as the Treasury funded its largest peacetime, non-recession deficit was returned immediately and identically as money market funds (MMFs) drew down on the vast RRP.

Normally, when the Treasury is borrowing that much money - over $2 trillion on an annual basis - it absorbs liquidity from the system as the bonds are bought mainly using bank deposits.

The liquidity eventually comes back into the system (the government borrows the money to spend it after all), but it is less “high-powered” and therefore not as beneficial for assets.

In sum, the RRP meant that what would have otherwise been very unfriendly conditions for stocks were instead supportive.

In fact, equities not only benefited from buoyant liquidity conditions, they were also aided by an unusually interest-rate resistant economy being flooded with public money. This has been pro-cyclical government spending on steroids.

What happens, then, to risk assets when the RRP goes to zero?

There are two aspects to consider: the effect in relation to funding the fiscal deficit, and the impact on money markets. Both ultimately mean a less easy ride for stocks and other risk assets.

On the deficit, the Treasury’s choice to fund most of it using bills has been a material support for stocks this year. MMFs can buy bills and were incentivized to do so as the yield on them rose above the RRP rate. As they were the ones with almost all the liquidity parked at the RRP, reserves have actually managed to rise this year, paradoxically so given the Fed’s ongoing quantitative tightening program.

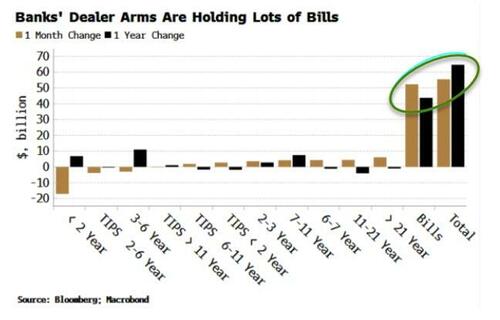

However, when the RRP goes to zero, government funding of the deficit will be functionally no different than if it had issued primarily longer-term debt (as is usual). Bank deposits and reserves are likely to fall more. Stocks will thus have less support when the RRP runs out. (Banks may decide to buy more of the issuance, which would mitigate the drop in reserves. But they have been heavy sellers of USTs, and look like they will continue to be until their duration risk falls further.)

Equities are also affected by what happens in funding markets, which could see an impact when the RRP goes to zero.

The market is haunted by what occurred in September 2019, when funding rates flared higher. Reserves had fallen to $1.5 trillion as the Fed progressed with its first shot at quantitative tightening. It had to promptly reverse its policy as repo rates started to spike.

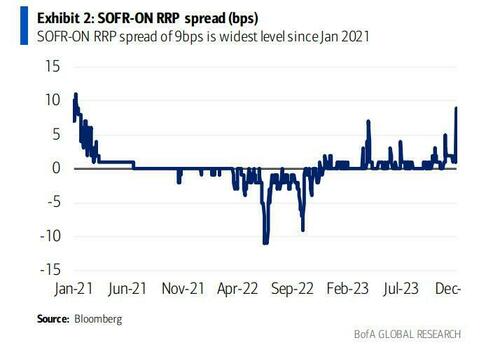

In a potential echo of 2019, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate unexpectedly jumped six basis points this week - a huge amount outside of Fed rate moves - causing jitters that funding flare-ups can happen even when reserves are at a much higher level. The rise was blamed on many factors, such as demand for extra funding due to the rally in Treasuries, reserve hoarding in anticipation of Basel III regulations, or as a buffer for underwater hold-to-maturity portfolios of bonds (i.e. what did it for SVB).

The SOFR has now reversed almost all of its jump, indicating that perhaps other factors, such as a combination of month-end demand and bank balance-sheets being clogged with bills, were primarily to blame.

Either way, the level of reserves that cause funding problems may well be higher than before. But assuming the jump in SOFR was idiosyncratic, today’s $4.3 trillion in actual and potential reserves — almost three times the 2019 level — is likely to be ample. (The $4.3 trillion comes from $3.4 trillion of reserves plus about $850 billion in the RRP — using the domestic RRP, as the foreign RRP tends to be sticky.)

Quantitative tightening will progressively take reserves lower, but the RRP going to zero in and of itself does not look like it will be the smoking gun for repo funding problems.

This raises the question though: when will the RRP go to zero?

Assuming the SOFR rate does not jump higher than the RRP again, it should take some 5-6 months to deplete the domestic RRP on the current trend.

In that time, QT could have taken out up to around $570 billion of reserves. That would mean total reserves would be in the order of $3.7 trillion (or closer to $3.6 trillion if we assume the Treasury wants to get its account at the Fed up to its intended $750 billion). That is still quite far above most estimates for the so-called lowest comfortable level of reserves of $2-$2.5 trillion.

All roads point to a less beneficent backdrop for assets once the RRP is exhausted. It has been a steady source of liquidity most of this year.

However, in the first instance its depletion represents the absence of a tailwind for markets, not necessarily an additional headwind. Yet as time goes on, QT will increasingly become a headwind without the RRP to leaven it.

Key things to keep an eye on are re-increases in the RRP, indicating extra reserves are being taken back out of the system, or a rising take-up in the Fed’s standing repo facility, which would point to potential funding problems.

All said and done, don’t put your spanner away yet, knowing how to plumb remains an essential skill.

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

The Federal Reserve’s reverse repo (RRP) facility has been a key support for liquidity and stocks this year. But it is falling. As it approaches zero, markets face much less benign conditions as a formidable tailwind is extinguished.

Everyone’s a plumber, or at least should be.

Not in the sense that we all need to get handy with a spanner, but in that every investor should have at least a basic knowledge of financial plumbing in the modern central-banking regime.

A good place to start is the Fed’s RRP facility.

It reached a peak of over $2.5 trillion in May this year. That’s a lot of cash to have hidden down the sofa. But it is now falling at a steady rate, down more than half from its peak. What happens when it goes to zero is a key question for markets and plumbers alike.

The RRP has been a veritable liquidity pump this year, acting as a source of stability for markets. Money that would otherwise have been taken out of the system as the Treasury funded its largest peacetime, non-recession deficit was returned immediately and identically as money market funds (MMFs) drew down on the vast RRP.

Normally, when the Treasury is borrowing that much money – over $2 trillion on an annual basis – it absorbs liquidity from the system as the bonds are bought mainly using bank deposits.

The liquidity eventually comes back into the system (the government borrows the money to spend it after all), but it is less “high-powered” and therefore not as beneficial for assets.

In sum, the RRP meant that what would have otherwise been very unfriendly conditions for stocks were instead supportive.

In fact, equities not only benefited from buoyant liquidity conditions, they were also aided by an unusually interest-rate resistant economy being flooded with public money. This has been pro-cyclical government spending on steroids.

What happens, then, to risk assets when the RRP goes to zero?

There are two aspects to consider: the effect in relation to funding the fiscal deficit, and the impact on money markets. Both ultimately mean a less easy ride for stocks and other risk assets.

On the deficit, the Treasury’s choice to fund most of it using bills has been a material support for stocks this year. MMFs can buy bills and were incentivized to do so as the yield on them rose above the RRP rate. As they were the ones with almost all the liquidity parked at the RRP, reserves have actually managed to rise this year, paradoxically so given the Fed’s ongoing quantitative tightening program.

However, when the RRP goes to zero, government funding of the deficit will be functionally no different than if it had issued primarily longer-term debt (as is usual). Bank deposits and reserves are likely to fall more. Stocks will thus have less support when the RRP runs out. (Banks may decide to buy more of the issuance, which would mitigate the drop in reserves. But they have been heavy sellers of USTs, and look like they will continue to be until their duration risk falls further.)

Equities are also affected by what happens in funding markets, which could see an impact when the RRP goes to zero.

The market is haunted by what occurred in September 2019, when funding rates flared higher. Reserves had fallen to $1.5 trillion as the Fed progressed with its first shot at quantitative tightening. It had to promptly reverse its policy as repo rates started to spike.

In a potential echo of 2019, the Secured Overnight Financing Rate unexpectedly jumped six basis points this week – a huge amount outside of Fed rate moves – causing jitters that funding flare-ups can happen even when reserves are at a much higher level. The rise was blamed on many factors, such as demand for extra funding due to the rally in Treasuries, reserve hoarding in anticipation of Basel III regulations, or as a buffer for underwater hold-to-maturity portfolios of bonds (i.e. what did it for SVB).

The SOFR has now reversed almost all of its jump, indicating that perhaps other factors, such as a combination of month-end demand and bank balance-sheets being clogged with bills, were primarily to blame.

Either way, the level of reserves that cause funding problems may well be higher than before. But assuming the jump in SOFR was idiosyncratic, today’s $4.3 trillion in actual and potential reserves — almost three times the 2019 level — is likely to be ample. (The $4.3 trillion comes from $3.4 trillion of reserves plus about $850 billion in the RRP — using the domestic RRP, as the foreign RRP tends to be sticky.)

Quantitative tightening will progressively take reserves lower, but the RRP going to zero in and of itself does not look like it will be the smoking gun for repo funding problems.

This raises the question though: when will the RRP go to zero?

Assuming the SOFR rate does not jump higher than the RRP again, it should take some 5-6 months to deplete the domestic RRP on the current trend.

In that time, QT could have taken out up to around $570 billion of reserves. That would mean total reserves would be in the order of $3.7 trillion (or closer to $3.6 trillion if we assume the Treasury wants to get its account at the Fed up to its intended $750 billion). That is still quite far above most estimates for the so-called lowest comfortable level of reserves of $2-$2.5 trillion.

All roads point to a less beneficent backdrop for assets once the RRP is exhausted. It has been a steady source of liquidity most of this year.

However, in the first instance its depletion represents the absence of a tailwind for markets, not necessarily an additional headwind. Yet as time goes on, QT will increasingly become a headwind without the RRP to leaven it.

Key things to keep an eye on are re-increases in the RRP, indicating extra reserves are being taken back out of the system, or a rising take-up in the Fed’s standing repo facility, which would point to potential funding problems.

All said and done, don’t put your spanner away yet, knowing how to plumb remains an essential skill.

Loading…