Under fire from House Republicans, the Biden administration has announced it will end the public health emergency over COVID-19 on May 11. But that raises a whole host of questions about the administration’s other policies.

With more than three months to go before that date, the White House will need to hash out what ending the emergency means for student loan cancellation, mask and vaccine mandates, testing requirements, and thousands of federal employees who are still working from home

.

HOUSE GOP SAYS BIDEN ‘CAVED’ ON ENDING COVID-19 HEALTH EMERGENCY

“There have been mixed messages coming out of the White House,” said Bob Moffit, a health and welfare policy fellow at the Heritage Foundation. “Biden said last year the pandemic is over and then extended the [emergency] deadline for another 90 days, then did so again in January. It’s time for the mixed messaging to end.”

Initiated in January and March 2020 by then-President Donald Trump, two public health emergencies related to the pandemic will be more than three years old before they’re allowed to expire late this spring. GOPers have been increasingly wary of extending those pauses as President Joe Biden took office and the disease gradually presented less of a threat.

The White House announced the pending end of those emergencies would come May 11.

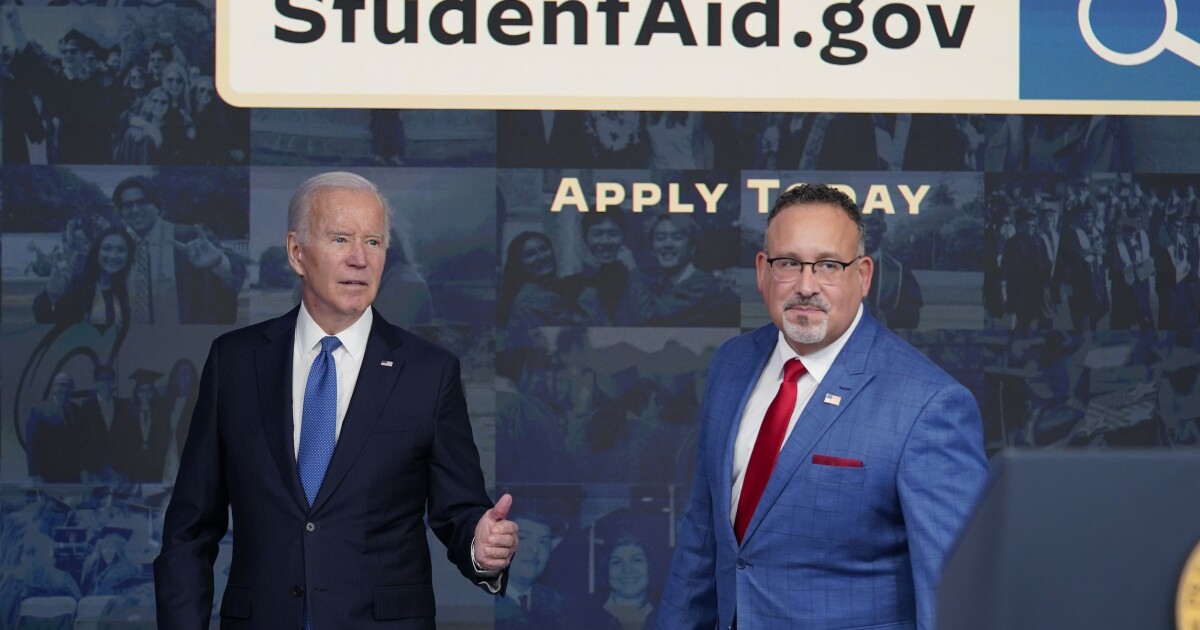

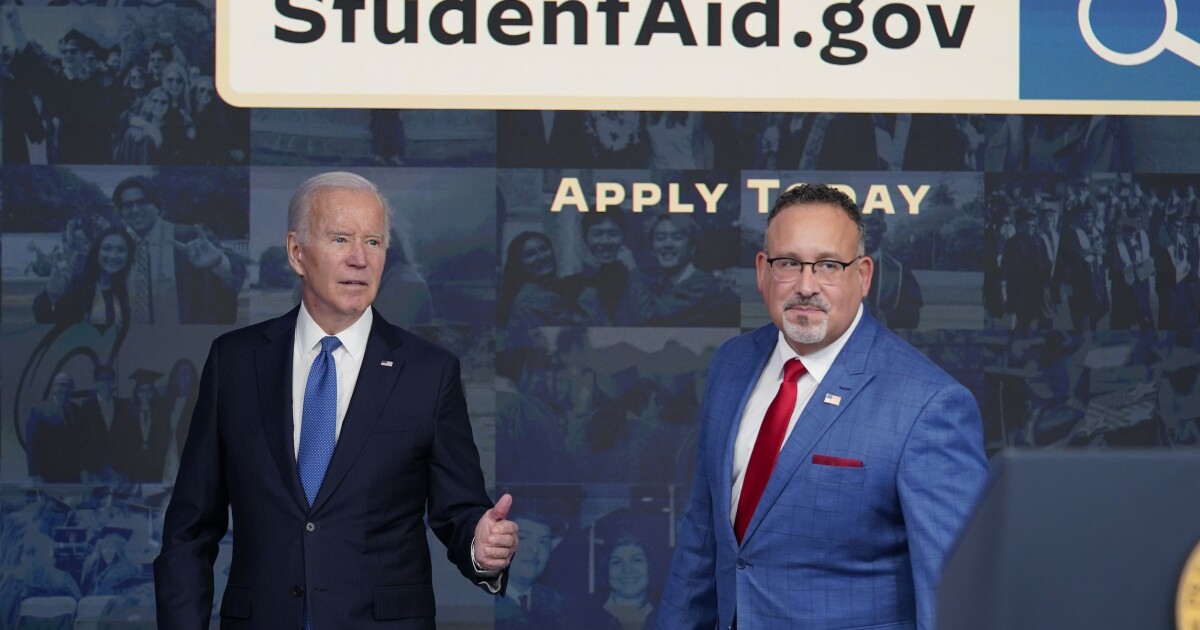

But that announcement itself raises a whole host of policy questions. Perhaps the biggest is Biden’s student loan cancellation program and the related student loan pause.

Both rest legally on the existence of a national emergency around COVID-19. The $500 billion cancellation program will be heard before the Supreme Court on Feb. 28, and the pause is set to last until June 30, nearly two months longer than the public health emergency used to justify it.

Fordham University law professor Jed Shugerman predicts the Supreme Court’s conservative majority will in fact strike down the program either way.

“1. They’re going to lose, 6-3 or worse. 2. Use the Higher Ed Act of 1965. 3. They’re running out of time,” he tweeted with a link to a Bloomberg article detailing the need for a student loan “plan B.”

One option would be for the administration to effectively start over by saying loans can be canceled via the Higher Education Act of 1965 rather than the emergency-related HEROES Act of 2003, which was passed in the wake of 9/11 and written with service members in mind.

If the Supreme Court strikes down the policy, it would be a major setback for Biden after he promised to cancel student loans on the campaign trail.

Moffit called the loan issue a textbook case of Biden stretching his authority via the pandemic.

“It’s a classic example of Biden overreaching and going beyond his statutory authority,” he said. “He’s using the pandemic as a pretext for a policy that is unrelated to public health.”

But there are other looming headaches with the formal end of the pandemic for the federal government.

Roughly half of federal employees are still working from home, which has drawn the ire of politicians ranging from Democratic Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser to House Oversight Committee Chairman James Comer (R-KY). That, too, was initiated at the outset of the pandemic and has largely remained in place even as private companies bring workers back in person.

The White House still requires proof of vaccination and negative tests for visitors and pool reporters covering the administration, a policy press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre defended just days ago.

The administration is also engaged in a legal battle over its ability to reimpose the federal mask mandate, which was struck down by a judge last April. It’s unclear what effect the end of the public health emergency will have, if any, on these debates.

Two issues that seem to be resolved are pandemic funding and expanded Medicaid. Congress has refused to issue new funding related to the pandemic for months despite pleading from the White House. Beginning in April, states will be allowed to begin removing ineligible people from Medicaid, and Pfizer and Moderna have already said they are considering selling their COVID-19 vaccines in the range of $110 to $130 per dose once the transition to the commercial marketplace is complete.

But Biden’s mixed messaging about the pandemic may not be over just yet.

Speaking with reporters on the South Lawn on Tuesday, he was asked about ending the emergency.

“Well, the emergency will end when the Supreme Court ends it,” Biden said. “We’ve extended it to May 15 to make sure we get everything done. That’s all. There’s nothing behind it at all.”

It’s unclear if Biden was confused and meant to refer to Title 42

, another pandemic-related policy dealing with immigration that the Supreme Court is expected to rule on over the summer. The White House did not respond to questions from the Washington Examiner seeking clarification about Biden’s comments.

House Republicans, meanwhile, have both taken credit for the emergency ending and continued efforts to end it sooner.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“I’m glad that my bill finally forced President Biden to act,”

said

Rep. Brett Guthrie (R-KY), who introduced the “Pandemic is Over” bill. “The American people have been living under a COVID-19 public health emergency for three years and should not allow President Biden four more months of emergency powers.”