–>

December 18, 2022

There is a particularly American Hanukah story that occurred when Washington and his troops were at Valley Forge during Christmas of 1777. Dan Adler’s article “Hanukkah at the White House” recounts this tale of George Washington’s encounter with a Jewish soldier: “In December, 1778, General George Washington had supper at the home of Michael Hart, a Jewish merchant in Easton, Pennsylvania. It was during the Hanukkah celebration, and Hart began to explain the customs of the holiday to his guest. Washington replied that he already knew about Hanukkah. He told Hart and his family of meeting the Jewish soldier at Valley Forge the previous year. (According to Washington, the soldier was a Polish immigrant who said he had fled his homeland because he could not practice his faith under the Prussian government there.) Hart’s daughter Louisa wrote the story down in her diary.” Rabbi Susan Grossman has written that, “[l]ike generations of Jews before him, that soldier served as a ‘light unto the nations’ (Isaiah 42:6), bringing inspiration and courage to a nation in its birth pangs. And he did so in a perfectly American way, a way in which a miracle did result, the miracle by which the light from one religion helps give comfort and courage to another.”

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

Rabbi Sharfman’s Account of Washington’s Hanukah with the Hart Family

Washington “was welcomed at the home of Corporal Michael Hart,” which is described as “a two-story stone building on the southeast corner of the public square, directly opposite the courthouse. His general store was on the first floor, his residence on the second. Michael Hart’s wife, Leah, prepared a kosher meal… in honor of the Hanukah festival, it being the sixth day of the holiday.” (To offer a mild correction, December 21, 1778, was the eighth and final day of Hanukah that year, since Hanukah ran from sundown, Sunday, December 13, 1778, until sundown, Monday, December 21st.)

Further, Louisa Hart would “proudly record” in her diary: “Let it be remembered that Michael Hart was a Jew, pious; a Jew reverencing and strictly observant of the Sabbath and festivals, dietary laws were also adhered to although he was compelled to be his own Schochet [ritual slaughterer]. Mark well that he, Washington, was then honored as first in peace, first in war and first in the hearts of his countrymen. Even during a short sojourn he became, for the hour, the guest of the worthy Jew.”

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

Washington’s Account of the Jewish Patriot

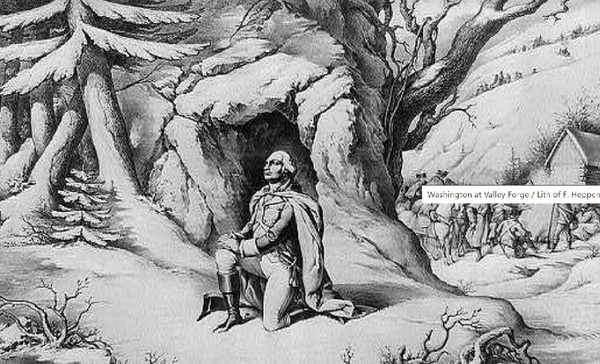

General Washington proceeded to explain to the Harts “how the Hanukah festival had inspired him during the previous year, when encamped at Valley Forge morale had sunk to its lowest ebb.” Due to the lack of warm clothes and protective footwear among Washington’s men, the severity of the winter had caused a feeling of despair to descend upon the commander-in-chief, and it was in this context that “a young Jewish private tendered the General a ray of hope.” The soldier, an emigrant out of Poland, was “proud to be a soldier for freedom and liberty.”

General Washington proceeded to explain to the Harts “how the Hanukah festival had inspired him during the previous year, when encamped at Valley Forge morale had sunk to its lowest ebb.” Due to the lack of warm clothes and protective footwear among Washington’s men, the severity of the winter had caused a feeling of despair to descend upon the commander-in-chief, and it was in this context that “a young Jewish private tendered the General a ray of hope.” The soldier, an emigrant out of Poland, was “proud to be a soldier for freedom and liberty.”

“It was the night of December 25, 1777. Christmas Day had been observed glumly and after eating their rations the men were bedded down for the night — all except the Jew. [Actually, the first night of Hanukah — beginning on the 25th of Kislev, 5538, on the Hebrew calendar — would have begun at sundown on December 24, 1777.] In a corner of the drafty wooden shack that served as their barracks, as quietly as possible, he lit his menorah, an eight-branched candelabrum that he had carried with him from overseas in his knapsack ever since the war had begun.” As he lit his menorah, the Jewish soldier wept softly to himself, a detail that did not escape the notice of General Washington, as he was making his appointed rounds. Approaching the soldier and touching him on the shoulder, as an aide-de-camp looked on, the general proceeded to ask, “Why do you cry, son?” to which the soldier replied, “Actually, I am not crying. I’m praying with tears for your victory.”

Per Rabbi Sharfman, the rest of the conversation went something like this:

“And what is this strange lamp?” asked the commander.

“This is my Hanukah lamp,” and the young man related briefly the ancient story — how long ago a small bedraggled but patriotic army routed a huge and powerful foe.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

“You are a Jew, a son of the Prophets, and you say we will be victorious?” the general declared, his eyes fixed on the flickering flames of the menorah.

“Yes,” the soldier unhesitatingly replied. “The God of Israel who helped the Maccabeans will help to build here a land of freedom for the oppressed.”

To the Harts, General Washington recalled on his luncheon visit when Hanukah was again celebrated, that the warmth of the glowing candlelight and the words of optimism and courage on that darkest night at Valley Forge uplifted him and gave him the fortitude to fight against all odds for victory.

So, take joy, Patriots, in the Festival of Lights this season. Stay in faith, and do what is necessary to be a light unto the nations. Happy Hanukah!

Paul Dowling has written about the Constitution, as well as articles for American Thinker, Independent Sentinel, Godfather Politics, Eagle Rising, and Free Thought Matters.

Image: Public Domain

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>