By Ven Ram, Bloomberg Markets Live reporter and strategist

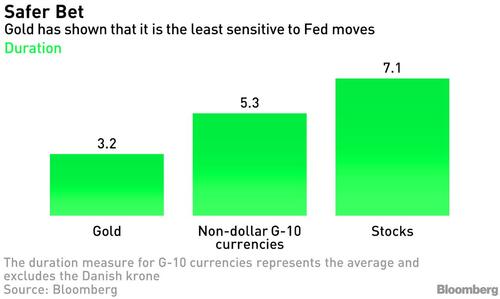

Gold is the most resilient asset to own if the Federal Reserve continues to raise rates, while stocks are the worst place to be, with non-dollar currencies falling between the two.

Gold has had an empirical duration of just over three years in the current Fed cycle, compared with stocks at 7.1 years. The non-dollar currencies that make up the G-10 have seen a duration of 5.3 years.

Duration measures the percentage change of an asset in reaction to a 1 percentage point shift in interest rates.

Gold is still hovering near its low for this cycle of $1,615 an ounce, a 12% decline since the start of the year that has come as the Fed raised its benchmark interest rate by 300 basis points, with another 75 basis points priced in from this week’s policy review.

Non-dollar G-10 currencies have seen an average duration of 5.3 years in the current cycle, highlighting their sensitivity to any perceptible shift in interest-rate differentials.

Still, stocks are the most sensitive to shifts in the Fed’s benchmark, with the S&P 500 demonstrating a duration of 7.1 years and the Nasdaq 100 about 9.6 years.

The sensitivity of stocks is in contrast to prior Fed cycles, when calculations show their duration was far less. The heightened duration in this cycle is a reflection of how low earnings’ yields on stocks had fallen before the Fed started raising rates.

Gold’s relative resilience echoes a study done back in 2020 that showed the metal had a good degree of convexity. In essence, gold stands to lose less when interest rates rise and gain more when rates fall by the same amount.

While the estimated duration then was 17, that measure has clearly fallen even more in this cycle, accentuating the effects of convexity.

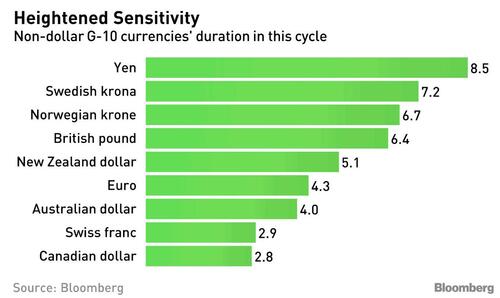

Among currencies, the yen, the Nordic complex and sterling have been the most vulnerable to the Fed’s rate increases as the chart shows:

The yen’s travails are well-known, with its descent to 150 per dollar last month in line with the shift in inflation-adjusted interest-rate differentials in favor of the greenback. Its duration of almost nine suggests that it would continue to be vulnerable should the Fed raise its benchmark to around 5% as the markets are now pricing in.

The high-duration measures of the Swedish and Norwegian currencies as well as the pound illustrate how sensitive the three economies are to developments outside their shores. In particular, sterling’s near-15% decline against the dollar this year is exaggerated in relation to moves in interest-rate differentials. As explored here in greater detail, the pound’s woes underscore its heightened correlation with the euro.

While the analysis on duration shows that gold is a relatively safe place to be in the currency cycle, it must be noted that it is still not completely immune to changes in interest rates.

All told, the study provides a useful ballpark of likely declines in various assets should the Fed continue to raise interest rates to drive inflation toward its 2% goal.

By Ven Ram, Bloomberg Markets Live reporter and strategist

Gold is the most resilient asset to own if the Federal Reserve continues to raise rates, while stocks are the worst place to be, with non-dollar currencies falling between the two.

Gold has had an empirical duration of just over three years in the current Fed cycle, compared with stocks at 7.1 years. The non-dollar currencies that make up the G-10 have seen a duration of 5.3 years.

Duration measures the percentage change of an asset in reaction to a 1 percentage point shift in interest rates.

Gold is still hovering near its low for this cycle of $1,615 an ounce, a 12% decline since the start of the year that has come as the Fed raised its benchmark interest rate by 300 basis points, with another 75 basis points priced in from this week’s policy review.

Non-dollar G-10 currencies have seen an average duration of 5.3 years in the current cycle, highlighting their sensitivity to any perceptible shift in interest-rate differentials.

Still, stocks are the most sensitive to shifts in the Fed’s benchmark, with the S&P 500 demonstrating a duration of 7.1 years and the Nasdaq 100 about 9.6 years.

The sensitivity of stocks is in contrast to prior Fed cycles, when calculations show their duration was far less. The heightened duration in this cycle is a reflection of how low earnings’ yields on stocks had fallen before the Fed started raising rates.

Gold’s relative resilience echoes a study done back in 2020 that showed the metal had a good degree of convexity. In essence, gold stands to lose less when interest rates rise and gain more when rates fall by the same amount.

While the estimated duration then was 17, that measure has clearly fallen even more in this cycle, accentuating the effects of convexity.

Among currencies, the yen, the Nordic complex and sterling have been the most vulnerable to the Fed’s rate increases as the chart shows:

The yen’s travails are well-known, with its descent to 150 per dollar last month in line with the shift in inflation-adjusted interest-rate differentials in favor of the greenback. Its duration of almost nine suggests that it would continue to be vulnerable should the Fed raise its benchmark to around 5% as the markets are now pricing in.

The high-duration measures of the Swedish and Norwegian currencies as well as the pound illustrate how sensitive the three economies are to developments outside their shores. In particular, sterling’s near-15% decline against the dollar this year is exaggerated in relation to moves in interest-rate differentials. As explored here in greater detail, the pound’s woes underscore its heightened correlation with the euro.

While the analysis on duration shows that gold is a relatively safe place to be in the currency cycle, it must be noted that it is still not completely immune to changes in interest rates.

All told, the study provides a useful ballpark of likely declines in various assets should the Fed continue to raise interest rates to drive inflation toward its 2% goal.