–>

September 7, 2022

The emotional cries of price gouging during the lockdown seem a distant remnant of the lockdowns, but the legal cases brought then, which are finally making their way through the courts, are a grim reminder of just how ignorant of economics and law our bureaucratic “betters” are. It makes one wonder: do government jobs attract the ignorant or do they simply lobotomize good men on arrival?

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

One such case, just reversed and remanded, The People v. Quality King, showcases just how absurd NY’s gouging law is and how unprincipled its courts. The law reads:

During any abnormal disruption of the market for consumer goods…vital and necessary for the health, safety and welfare of consumers…no party…shall sell…such goods…for an amount which represents an unconscionably excessive price.

Lord knows, the geniuses up in Albany couldn’t have been more pleased with themselves. But discerning the law’s meaning would require work more for oracles than the citizenry. What constitutes an abnormal disruption, what products are vital and necessary, and what price is so excessive as to be unconscionable?

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

Gouging, it would seem, was now to be adjudicated by the same legal standard Justice Potter Stewart famously set forth in his concurrence to Jacobellis v. Ohio for hard-core pornography: But I know it when I see it….” An otherwise laughable standard, if only we weren’t governed by it.

Since Jacobellis, thankfully, the Court has reconsidered such arbitrariness, writing in Grayned v Rockford:

Vague laws offend several important values. First, because we assume that man is free to steer between lawful and unlawful conduct, we insist that laws give the person of ordinary intelligence a reasonable opportunity to know what is prohibited, so that he may act accordingly. Vague laws may trap the innocent by not providing fair warning. [Fn. omitted.] Second, if arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement is to be prevented, laws must provide explicit standards for those who apply them. [Fn. omitted.] A vague law impermissibly delegates basic policy matters to policemen, judges, and juries for resolution on an ad hoc and subjective basis, with the attendant dangers of arbitrary and discriminatory application. [Fn. omitted.]

Never has the void-for-vagueness doctrine been so superbly articulated and never so thoroughly ignored. Not only is the “unconscionably excessive” language in the New York statute unconstitutionally vague—defying the principle of separation of powers—the law itself illegally “delegates basic policy matters” to the judicial branch.

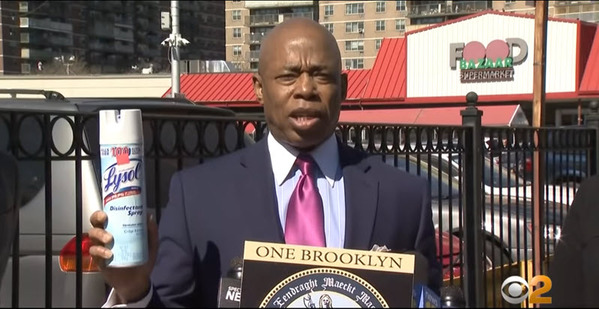

Image: Lysol in the crosshairs. YouTube screen grab.

In Quality King, the court was asked to decide at what point the defendant should have known there was an official disruption in the market triggering the statute. Was it the declaration of a national emergency by the president? No. A governor-declared state emergency? Certainly not. The court ruled it was when “the CDC tweeted, ‘[n]ow is the time for US businesses, hospitals, and communities to begin preparing for the possible spread of #COVID19’” (bolded emphasis added; italicized emphasis in original). Don’t know how they could have missed that.

Next, the court was asked to decide whether Lysol spray was “vital and necessary?” Admitting these words “are not defined in the statute,” the judges appealed to Websters to reimagine the phrase as “of the utmost importance” and “absolutely needed.” Despite the media’s 2020-induced hysteria, we have known throughout recorded history that respiratory viruses have never been transmitted from surfaces and, even if they were, soap and water effectively clean surfaces. Certainly, Lysol spray was neither of the “utmost importance” nor “absolutely needed.” But facts are anathema to a liberal court; what’s important is how people feel: Lysol was, “at least in the eyes of consumers, of the utmost importance and absolutely needed to address the terrible danger.”

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

Finally, the court needed to decide if defendant’s prices were “unconscionably excessive.” Here it decided not to consult Webster’s but, for the record, unconscionable is defined as “shockingly unfair, so bad as to be immoral.” And indeed, they ruled that a bottle of Lysol priced at $7.37, when it used to be $5.50, shocks the conscience. Biden’s inflation? Not so much.

So, for Quality King to have “known what is prohibited, so it may act accordingly,” it would have needed to constantly monitor Twitter for potentially statute-triggering tweets, poll its customers to see what products they believed were vital and necessary, and then petition the court for an endorsement of its prices. Business as usual in NY.

Quality King also asked the court at oral arguments (go to 1:50) how a law so ambiguous could be constitutional:

On the constitutional point, think of this: on the exact same record, the exact same facts, the exact same arguments, statute, and law, one judge says ‘not grossly excessive.’ If this court says unconscionably excessive, I submit this proves our point. It establishes our position that nobody in Quality King could know the answer in advance, rendering the law unconstitutionally vague.

The court, while seeming to agree, simply dismissed the argument anyway with a stunning abruptness:

To be sure, General Business Law § 396-r does not contain a quantitative metric for ascertaining whether a given price is unconscionably excessive or unconscionably extreme. [snip] The absence of such a metric, however, does not affect the statute’s constitutionality…appeal dismissed.

As preposterously unconstitutional as the actual law is, and as bankrupt as the court’s reasoning was, it’s all a distraction from the real story which is, as Milton Friedman quipped, that “gougers deserve a medal.”

It’s as if every lawmaker skipped Economics 101. Its bedrock principle states that the intersection of the supply and demand curve determines price. In an emergency, demand soars initially, much faster than supply can adjust, so prices rise. It is those higher prices that signal to and incentivize the market to create more supply—more of the product people desperately need. Importantly, higher prices also encourage consumers to limit their use of the suddenly scarce resource, so shelves don’t instantly go bare. How many basements are still filled with toilet paper?

Anti-gouging laws, whether ambiguously unconstitutional or not, rather than protecting the public welfare, do exactly the opposite: guaranteeing shortages that will persist far longer than they might otherwise have.

This is not simply theoretical; we lived it. Gouging laws created so much uncertainty for merchants that, instead of marshaling their resources to alleviate the market disruption, they simply fled the marketplace. Amazon, not knowing how to comply with a national patchwork of conflicting and arbitrary laws, sent cryptic warnings on gouging to its merchants, including those whose prices hadn’t changed. Instead of risking suspension, hundreds of merchants simply removed listings. Amazon erased the listings of those that didn’t. During the height of the pandemic, Amazon withdrew 530,000 offers of critically needed goods rather than risk arbitrary prosecution.

In a University of Chicago poll of leading economists on price gouging, the results showed that 77% disagreed or strongly disagreed with price gouging laws and only 7% agreed. Michael Salinger, the FTC’s former director of the Bureau of Economics, wrote, “gouging laws stand in the way of the normal workings of the competitive market.” Pacific Legal Foundation’s Steve Simpson unequivocally stated, “price gouging laws are economical just idiotic,” “irrational and arbitrary,” and a “violation of the right to due process.”

Gouging laws are the emotional knee-jerk response of unthinking legislators who can’t miss an opportunity to virtue signal their “excellence,” no matter how much harm it does. And vague, arbitrary laws, whether gouging or not, offend the Constitution, paralyze the economy, and make criminals of honest men. Surely, we can do better.

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>