Submitted by Jack Raines via Young Money,

Anytime stocks go down, you will see three comments from the investing community:

-

"Time in the market beats timing the market"

-

Warren Buffett quotes about buying when there is "blood in the streets"

-

References to Dot Com bubble declines and the subsequent gains of today's biggest tech companies from those lows

Since January, I have seen examples of all three with increasing frequency.

Remember, time in the market beats timing the market.

— Miles Deutscher (@milesdeutscher) February 19, 2022

In crypto this is especially true. Just ask those who had conviction and held through 2018-2020.

You won’t be able to time the exact tops and bottoms, but stay in the market long enough and you’ll be rewarded.

When there is blood in the streets, stay ✨zesty✨ and buy #Bitcoin! 🤩💎🚀

— Miss Teen Crypto (@missteencrypto) January 6, 2022

Stock declines from the peak of the dot com bubble to the bottom:

— Jon Erlichman (@JonErlichman) May 5, 2022

Adobe: -56%

Microsoft: -56%

Amazon: -75%

Nvidia: -75%

Apple: -78%

Stock gains over the next 19 years:

Apple: +58,746%

Nvidia: +33,818%

Amazon: +19,405%

Adobe: +6,250%

Microsoft: +1,240%

Like clockwork, baby.

At face value, these comments aren't bad. It's true, time in the market does, historically, beat timing the market. It's true, you will make the biggest returns by purchasing stocks when panic is the highest. And it's true, if you had bought Apple or Amazon in 2003, you would be rich right now.

Here are some other things that are true.

"Time in the market beats timing the market" doesn't apply to previously overpriced, unprofitable "high growth" companies, a zero-sum cryptocurrency, or any other singular investment.

Blood in the streets might be a good time to buy indexes, but many individual investments that are down 90% will go to zero.

And do you really think that you would have the foresight to pick the next iPhone and Amazon Web Services five years before they launch? Because I promise you that Cisco, the backbone of internet infrastructure at the time, would have seemed like a no-brainer in 2001. It still hasn't reclaimed its highs. And plenty of other high-flyers went bust.

Stock declines from the peak of the dot com bubble to the bottom:

— Ian Bezek (@irbezek) May 7, 2022

WorldCom: -100%

Enron: -100%

Lucent: -90%+

Yahoo: -90%+

CMGI: -99%

Cisco: -80%

Gain over next 19 years:

WorldCom: N/A

Enron: N/A

Lucent: Not much

Yahoo: A little

CMGI: None at all

Cisco: Still shy of '99 highs. https://t.co/g75aERGqgF

Individual stocks are not "the market." Blood is only in the streets because some companies are, in fact, dying. And your "disruptive" company probably won't create a consumer product used by billions or the largest cloud software platform in history.

But we like being right. And recent markets are proving many of our investments wrong. It's painful and humbling to accept that we bought something bad, we lost money on it, and we won't earn it back. But what if we weren't wrong? What if we can convince ourselves that our investments will recover?

So we apply broad market commentary, vague Buffett-isms, and examples of survivorship bias to our own individual investments.

The perversion of all of these ideas to rationalize our current portfolios leads us to a singular hope:

"This will climb back to all-time highs."

And that, my friends, is called price anchoring. The fallacy of price anchoring has caused, and will continue to cause, a lot of pain in the streets.

Anchor Down

Anchoring is a cognitive bias in which the use of an arbitrary benchmark such as a purchase price or sticker price carries a disproportionately high weight in one's decision-making process...

In the context of investing, one consequence of anchoring is that market participants with an anchoring bias tend to hold investments that have lost value because they have anchored their fair value estimate to the original price rather than to fundamentals. As a result, market participants assume greater risk by holding the investment in the hope the security will return to its purchase price.

We are all guilty of price anchoring on both the high and low ends. You want to buy a stock, but it climbed from $50 to $100 since you began watching it. $50 is now your anchor point, and $100 feels expensive. Is $100 actually expensive? I have no idea. If the company's revenue and earnings exploded, $100 right now could actually be a better deal than $50 a year ago. But we don't concentrate on the value of the company's business, we compare the current price to previous prices.

We hope that it will fall close to $50 again, because that feels "fair" to us. In reality, if the business is executing, it may never go that low again. If the stock does fall to $50, the business model may very well be broken, meaning that at that point, it's not a good investment. Price anchoring replaces business evaluation with price comparison, often to investors' folly.

Price anchoring is even more pervasive when comparing to previous highs. Everyone and their mother was shilling bitcoin when it crossed $60k, and $100k seemed inevitable. So you took a massive position at $65k. Now it's down to $29k.

Electric vehicles have been hot, so you bought the Rivian IPO at $130 per share (and a >$100B valuation). It's now sitting at $20 per share.

So now they feel cheap. Bitcoin is down 50%, and everyone is still talking about it. It must be cheap. Rivian is down 80%, and EVs aren't going anywhere. It must be cheap.

What gets missed in this conclusion is whether or not our buy point made sense in the first place. What we consider "cheap" compared to recent highs might really just be a reversion to normal valuations. What if the current prices are reasonable, and it was our top-tick purchase that was the real aberration?

Once again, price anchoring replaces business evaluation with price comparison, often to investors' folly.

The Two Sides of Value

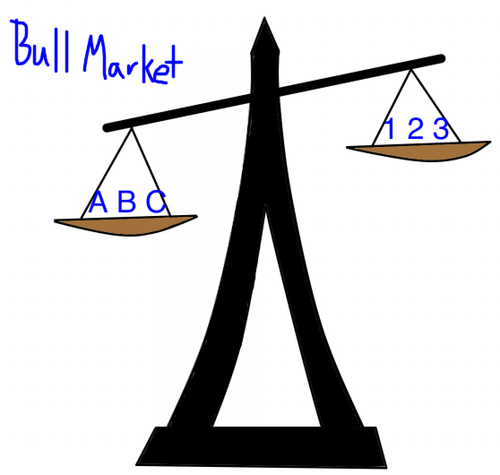

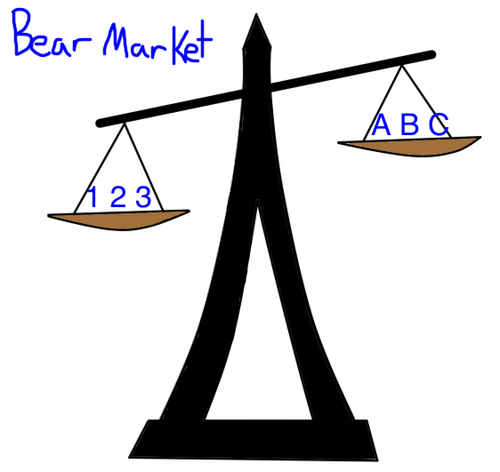

Traditional finance teaches that every asset can be valued on fundamental metrics alone: cash flows, earnings, capital structure, and sales growth are all that matter. But in reality, we know that isn't true. Fundamentals don't have a monopoly on valuations. Fundamentals are engaged in a perpetual game of tug-of-war with stories.

The story of what an asset "could be" plays a huge role in what investors are willing to pay for an asset. Steve Jobs understood the role of storytelling better than most. Elon Musk's storytelling has turned Tesla into the world's most valuable automaker while spending $0 on marketing. Bitcoin's entire value is largely predicated on stories, from an inflation hedge, to a foil for the villainous Federal Reserve, to the power of the almighty permission-less blockchain. The value that the market gives these stories determines the price that you will pay for these assets.

The thing is, fundamentals and stories are dynamic, not static.

Fundamentals and stories operate on a sliding scale. During periods of euphoria, stories reign supreme.

During periods of decline, fundamentals are the only metric that can stop the bleeding.

This has never been more apparent than in the last two years. At peak euphoria, ARKK was up 400%, energy and value were dead, and SPACs would climb 300% because of a good powerpoint presentation.

Now? Those stories aren't worth the paper you could write them on.

The paradox is that you can make obscene returns by investing in stories, so long as you never believe the stories that you buy.

No Two Stories Are the Same

Everything that happens once can never happen again. But everything that happens twice will surely happen a third time.

The Alchemist

When a child touches a hot stove, he gets burned. When he gets burned, he is unlikely to touch the stove again. But that doesn't prevent other children who have never touched a hot stove from trying it out.

It's no coincidence that 20 years after the Dot Com bubble crash, we're seeing it happen again. 20 years is enough time to cycle in a new generation of investors. Investors whose entire adult lives have taken place in the greatest bull market in history. Whose one "crash" in March 2020 fully recovered in months, as the market resumed its climb to all-time-highs. Investors who, for all intents and purposes, believe that stocks really do only go up.

A new generation of children who never touched the hot stove.

After 20 years, a new class of investors fell in love with a new story. The players and the pieces changed, but the plot is always the same. Enticed by the dream of quick returns, by a good story, they dive head first into speculation.

And it works. For a while. If you invested in a good story at chapter one, you likely saw incredible returns. You share the story with more people, and they share it as well. Soon everyone is talking about this story. Everyone wants to get in.

Soon, the community of investors becomes an echo chamber of fervent supporters. Bullish opinions are amplified, bearish voices are excommunicated.

As Morgan Housel says, "Nothing is more persuasive than the opinion you desperately want to believe is true.

Nothing is more persuasive than the opinion you desperately want to believe is true.

— Morgan Housel (@morganhousel) May 24, 2021

And there are no opinions that you desperately want to be true more than those that you believe will make you money.

Unfortunately, from books to movies to financial markets, all good stories eventually come to an end. And that's the difficult part of investing in stories: you can make amazing sums of money as long as you don't believe the stories that you buy. Because if you believe, you'll never sell. And if you never sell, your money disappears with the story.

But if you didn't believe in the story, you probably never bought it in the first place.

It's a tough lesson to learn, especially in this era. After all, for a decade, every dip was a buying opportunity, especially in growth stocks and crypto. Trigger-happy investors were paid handsomely for their risk profiles. But once the story ends, it's over.

The conditions that led certain individual equities to reach their outsized valuations will never occur in the same way again.

If you tripled down on growth stocks because they were "only" trading at 20x sales after a 50% pullback, just to watch them fall another 50%, are you going to be as careless during the next downtrend?

If you invested in SPACs because of their high-flying projections, and you lost money when they grossly missed their marks, are you going to continue throwing money at these same SPACs?

If your NFTs dropped 95% as liquidity evaporated from the market sector, are you going to throw thousands more at JPEGs?

Of course not. You learned from your experiences. It took the pain of a loss to offset the blinding euphoria of easy gains.

Once a truth is realized, it can't be unlearned.

Dot Com stocks didn't bubble again in 2004. We didn't have another housing crisis in 2013. There wasn't a second Tulip Bubble after the first one imploded.

Everything that happens once can never happen again. But everything that happens twice will surely happen a third time.

Greed, euphoria, bubbles, excess? Those are timeless characteristics of humanity. But they never manifest themselves the same way. They need new players, new pieces, new markets.

The same investors won't fall victim to the same schemes twice. But everyone who is underwater on their positions desperately hopes that they will recover. After all, for a decade, buying the dip solved every problem.

An entire generation of investors grew up in a market that only went up and to the right. Millions more joined the market during Covid lockdowns, and everything they bought went to the moon. "Normal," for this group of novel investors, is rocket ship emojis, absurd valuations, and insane returns. But the party is over.

Like a former addict going through withdrawals, accepting the reality of recent financial markets is a painful experience.

And the rehab process is going to be painful. Every green day will be filled with investors trying to buy the dip, to time the bottom. Bear market rallies will ensue as they try to recapture that euphoria.

But once a truth is realized, it can't be unlearned. As a kid, once you find out that Santa isn't real, you can't just decide to believe in Santa again. It doesn't work.

The majority of market participants who were fleeced by the stories of 2020 and 2021 won't be so careless again. They snapped back to reality. They see through the SPAC projections. The crypto roadmaps. The NFT stories. As a whole, they won't fall victim to the same schemes. Their greed won't manifest itself in the same ways, because they know it isn't true.

These securities that are down 90%? Most won't reclaim their all-time highs because the euphoria needed to get them there no longer exists.

But sure, that company that you paid 80x sales for in February 2021 will definitely hit all-time highs in another year or two. Just need to double down to lower that cost basis. No price is too high for growth, right?

- Jack

If you liked this piece, make sure to subscribe!

Submitted by Jack Raines via Young Money,

Anytime stocks go down, you will see three comments from the investing community:

-

“Time in the market beats timing the market”

-

Warren Buffett quotes about buying when there is “blood in the streets”

-

References to Dot Com bubble declines and the subsequent gains of today’s biggest tech companies from those lows

Since January, I have seen examples of all three with increasing frequency.

Remember, time in the market beats timing the market.

In crypto this is especially true. Just ask those who had conviction and held through 2018-2020.

You won’t be able to time the exact tops and bottoms, but stay in the market long enough and you’ll be rewarded.

— Miles Deutscher (@milesdeutscher) February 19, 2022

When there is blood in the streets, stay ✨zesty✨ and buy #Bitcoin! 🤩💎🚀

— Miss Teen Crypto (@missteencrypto) January 6, 2022

Stock declines from the peak of the dot com bubble to the bottom:

Adobe: -56%

Microsoft: -56%

Amazon: -75%

Nvidia: -75%

Apple: -78%Stock gains over the next 19 years:

Apple: +58,746%

Nvidia: +33,818%

Amazon: +19,405%

Adobe: +6,250%

Microsoft: +1,240%— Jon Erlichman (@JonErlichman) May 5, 2022

Like clockwork, baby.

At face value, these comments aren’t bad. It’s true, time in the market does, historically, beat timing the market. It’s true, you will make the biggest returns by purchasing stocks when panic is the highest. And it’s true, if you had bought Apple or Amazon in 2003, you would be rich right now.

Here are some other things that are true.

“Time in the market beats timing the market” doesn’t apply to previously overpriced, unprofitable “high growth” companies, a zero-sum cryptocurrency, or any other singular investment.

Blood in the streets might be a good time to buy indexes, but many individual investments that are down 90% will go to zero.

And do you really think that you would have the foresight to pick the next iPhone and Amazon Web Services five years before they launch? Because I promise you that Cisco, the backbone of internet infrastructure at the time, would have seemed like a no-brainer in 2001. It still hasn’t reclaimed its highs. And plenty of other high-flyers went bust.

Stock declines from the peak of the dot com bubble to the bottom:

WorldCom: -100%

Enron: -100%

Lucent: -90%+

Yahoo: -90%+

CMGI: -99%

Cisco: -80%Gain over next 19 years:

WorldCom: N/A

Enron: N/A

Lucent: Not much

Yahoo: A little

CMGI: None at all

Cisco: Still shy of ’99 highs. https://t.co/g75aERGqgF— Ian Bezek (@irbezek) May 7, 2022

Individual stocks are not “the market.” Blood is only in the streets because some companies are, in fact, dying. And your “disruptive” company probably won’t create a consumer product used by billions or the largest cloud software platform in history.

But we like being right. And recent markets are proving many of our investments wrong. It’s painful and humbling to accept that we bought something bad, we lost money on it, and we won’t earn it back. But what if we weren’t wrong? What if we can convince ourselves that our investments will recover?

So we apply broad market commentary, vague Buffett-isms, and examples of survivorship bias to our own individual investments.

The perversion of all of these ideas to rationalize our current portfolios leads us to a singular hope:

“This will climb back to all-time highs.”

And that, my friends, is called price anchoring. The fallacy of price anchoring has caused, and will continue to cause, a lot of pain in the streets.

Anchor Down

Anchoring is a cognitive bias in which the use of an arbitrary benchmark such as a purchase price or sticker price carries a disproportionately high weight in one’s decision-making process…

In the context of investing, one consequence of anchoring is that market participants with an anchoring bias tend to hold investments that have lost value because they have anchored their fair value estimate to the original price rather than to fundamentals. As a result, market participants assume greater risk by holding the investment in the hope the security will return to its purchase price.

We are all guilty of price anchoring on both the high and low ends. You want to buy a stock, but it climbed from $50 to $100 since you began watching it. $50 is now your anchor point, and $100 feels expensive. Is $100 actually expensive? I have no idea. If the company’s revenue and earnings exploded, $100 right now could actually be a better deal than $50 a year ago. But we don’t concentrate on the value of the company’s business, we compare the current price to previous prices.

We hope that it will fall close to $50 again, because that feels “fair” to us. In reality, if the business is executing, it may never go that low again. If the stock does fall to $50, the business model may very well be broken, meaning that at that point, it’s not a good investment. Price anchoring replaces business evaluation with price comparison, often to investors’ folly.

Price anchoring is even more pervasive when comparing to previous highs. Everyone and their mother was shilling bitcoin when it crossed $60k, and $100k seemed inevitable. So you took a massive position at $65k. Now it’s down to $29k.

Electric vehicles have been hot, so you bought the Rivian IPO at $130 per share (and a >$100B valuation). It’s now sitting at $20 per share.

So now they feel cheap. Bitcoin is down 50%, and everyone is still talking about it. It must be cheap. Rivian is down 80%, and EVs aren’t going anywhere. It must be cheap.

What gets missed in this conclusion is whether or not our buy point made sense in the first place. What we consider “cheap” compared to recent highs might really just be a reversion to normal valuations. What if the current prices are reasonable, and it was our top-tick purchase that was the real aberration?

Once again, price anchoring replaces business evaluation with price comparison, often to investors’ folly.

The Two Sides of Value

Traditional finance teaches that every asset can be valued on fundamental metrics alone: cash flows, earnings, capital structure, and sales growth are all that matter. But in reality, we know that isn’t true. Fundamentals don’t have a monopoly on valuations. Fundamentals are engaged in a perpetual game of tug-of-war with stories.

The story of what an asset “could be” plays a huge role in what investors are willing to pay for an asset. Steve Jobs understood the role of storytelling better than most. Elon Musk’s storytelling has turned Tesla into the world’s most valuable automaker while spending $0 on marketing. Bitcoin’s entire value is largely predicated on stories, from an inflation hedge, to a foil for the villainous Federal Reserve, to the power of the almighty permission-less blockchain. The value that the market gives these stories determines the price that you will pay for these assets.

The thing is, fundamentals and stories are dynamic, not static.

Fundamentals and stories operate on a sliding scale. During periods of euphoria, stories reign supreme.

During periods of decline, fundamentals are the only metric that can stop the bleeding.

This has never been more apparent than in the last two years. At peak euphoria, ARKK was up 400%, energy and value were dead, and SPACs would climb 300% because of a good powerpoint presentation.

Now? Those stories aren’t worth the paper you could write them on.

The paradox is that you can make obscene returns by investing in stories, so long as you never believe the stories that you buy.

No Two Stories Are the Same

Everything that happens once can never happen again. But everything that happens twice will surely happen a third time.

The Alchemist

When a child touches a hot stove, he gets burned. When he gets burned, he is unlikely to touch the stove again. But that doesn’t prevent other children who have never touched a hot stove from trying it out.

It’s no coincidence that 20 years after the Dot Com bubble crash, we’re seeing it happen again. 20 years is enough time to cycle in a new generation of investors. Investors whose entire adult lives have taken place in the greatest bull market in history. Whose one “crash” in March 2020 fully recovered in months, as the market resumed its climb to all-time-highs. Investors who, for all intents and purposes, believe that stocks really do only go up.

A new generation of children who never touched the hot stove.

After 20 years, a new class of investors fell in love with a new story. The players and the pieces changed, but the plot is always the same. Enticed by the dream of quick returns, by a good story, they dive head first into speculation.

And it works. For a while. If you invested in a good story at chapter one, you likely saw incredible returns. You share the story with more people, and they share it as well. Soon everyone is talking about this story. Everyone wants to get in.

Soon, the community of investors becomes an echo chamber of fervent supporters. Bullish opinions are amplified, bearish voices are excommunicated.

As Morgan Housel says, “Nothing is more persuasive than the opinion you desperately want to believe is true.

Nothing is more persuasive than the opinion you desperately want to believe is true.

— Morgan Housel (@morganhousel) May 24, 2021

And there are no opinions that you desperately want to be true more than those that you believe will make you money.

Unfortunately, from books to movies to financial markets, all good stories eventually come to an end. And that’s the difficult part of investing in stories: you can make amazing sums of money as long as you don’t believe the stories that you buy. Because if you believe, you’ll never sell. And if you never sell, your money disappears with the story.

But if you didn’t believe in the story, you probably never bought it in the first place.

It’s a tough lesson to learn, especially in this era. After all, for a decade, every dip was a buying opportunity, especially in growth stocks and crypto. Trigger-happy investors were paid handsomely for their risk profiles. But once the story ends, it’s over.

The conditions that led certain individual equities to reach their outsized valuations will never occur in the same way again.

If you tripled down on growth stocks because they were “only” trading at 20x sales after a 50% pullback, just to watch them fall another 50%, are you going to be as careless during the next downtrend?

If you invested in SPACs because of their high-flying projections, and you lost money when they grossly missed their marks, are you going to continue throwing money at these same SPACs?

If your NFTs dropped 95% as liquidity evaporated from the market sector, are you going to throw thousands more at JPEGs?

Of course not. You learned from your experiences. It took the pain of a loss to offset the blinding euphoria of easy gains.

Once a truth is realized, it can’t be unlearned.

Dot Com stocks didn’t bubble again in 2004. We didn’t have another housing crisis in 2013. There wasn’t a second Tulip Bubble after the first one imploded.

Everything that happens once can never happen again. But everything that happens twice will surely happen a third time.

Greed, euphoria, bubbles, excess? Those are timeless characteristics of humanity. But they never manifest themselves the same way. They need new players, new pieces, new markets.

The same investors won’t fall victim to the same schemes twice. But everyone who is underwater on their positions desperately hopes that they will recover. After all, for a decade, buying the dip solved every problem.

An entire generation of investors grew up in a market that only went up and to the right. Millions more joined the market during Covid lockdowns, and everything they bought went to the moon. “Normal,” for this group of novel investors, is rocket ship emojis, absurd valuations, and insane returns. But the party is over.

Like a former addict going through withdrawals, accepting the reality of recent financial markets is a painful experience.

And the rehab process is going to be painful. Every green day will be filled with investors trying to buy the dip, to time the bottom. Bear market rallies will ensue as they try to recapture that euphoria.

But once a truth is realized, it can’t be unlearned. As a kid, once you find out that Santa isn’t real, you can’t just decide to believe in Santa again. It doesn’t work.

The majority of market participants who were fleeced by the stories of 2020 and 2021 won’t be so careless again. They snapped back to reality. They see through the SPAC projections. The crypto roadmaps. The NFT stories. As a whole, they won’t fall victim to the same schemes. Their greed won’t manifest itself in the same ways, because they know it isn’t true.

These securities that are down 90%? Most won’t reclaim their all-time highs because the euphoria needed to get them there no longer exists.

But sure, that company that you paid 80x sales for in February 2021 will definitely hit all-time highs in another year or two. Just need to double down to lower that cost basis. No price is too high for growth, right?

– Jack

If you liked this piece, make sure to subscribe!