Authored by Carlo J.V. Caro via RealClearDefense,

Unlike many movements that adopt the mantle of liberation for political gain, Hezbollah’s portrayal as a liberating force is tied to a long-standing cultural memory of foreign oppression, from the Ottoman Empire to the French Mandate. Understanding how Hezbollah leveraged this identity requires an examination of Lebanon's history of local resistance, which was not always violent but often manifested as passive defiance, economic self-sufficiency, and cultural preservation, especially among marginalized Shia agrarian communities.

During the Ottoman era, southern Lebanon’s Shia population was systematically neglected and excluded by the ruling class, which favored the Sunni elite and Christian coastal merchants. Ottoman tax farmers exploited Shia agricultural communities in the Bekaa Valley and southern Lebanon, fostering deep resentment toward external governance. The Shia community's refusal to pay taxes or serve in the Ottoman military, a resistance that subtly persisted under the French Mandate, reinforced their self-perception as an oppressed yet resilient group. Though largely nonviolent, this resistance cultivated a cultural aversion to foreign control, which Hezbollah later capitalized on.

In contrast, Mount Lebanon operated under a semi-autonomous Mutasarrifate system, allowing Druze and Maronite elites to negotiate governance with the Ottomans—an advantage not extended to the Shia of southern Lebanon. While Maronites and Druze enjoyed self-governance and strong trade ties with European powers, the Shia were relegated to peripheral roles, fostering isolation and mistrust toward both central authorities and foreign powers. This fragmented Lebanese identity, with allegiance often directed toward local feudal lords or religious leaders, persisted into the post-Ottoman period, worsened by the French Mandate's efforts to centralize control in Beirut, further marginalizing southern Lebanon.

When the French assumed control of Lebanon after World War I, they introduced modern institutions but often at the expense of local autonomy, particularly in rural areas. While infrastructure development flourished in Beirut and other urban centers, the agrarian Shia south was largely neglected, reinforcing economic isolation and discontent. The French also shaped Lebanon's political system to the detriment of the Shia. The Confessionalist system they implemented ensured minimal political representation for the Shia, who were overshadowed by Maronite Christians and Sunni Muslims. This marginalization persisted after independence, reaching a breaking point during the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990). Shia exclusion from economic and political power became a critical factor in Hezbollah’s rise, as it united the community under its banner. The political system, rooted in colonialism, fueled Hezbollah's anti-colonial narrative, allowing it to position itself as the true heir to Lebanon’s liberation struggles.

Hezbollah effectively co-opted the Shia principle of sabr (steadfastness), a deeply ingrained religious and cultural value stemming from the martyrdom of Imam Hussein at Karbala in 680 CE. The theme of enduring suffering and injustice while remaining resolute became central to Hezbollah’s narrative, aligning with both the historical experience of foreign oppression and the contemporary struggles of Lebanese Shia. When Hezbollah claimed responsibility for Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000, it framed the event as a validation of the Shia legacy of perseverance, demonstrating that victory could be achieved through unwavering resistance.

Hezbollah further reinforced this narrative by invoking the concept of muwajaha (confrontation), a term in Shia tradition closely tied to the symbolic power of Karbala. In southern Lebanon, muwajaha extends beyond military struggle to encompass the religious and cultural duty to resist oppression. Hassan Nasrallah consistently framed the conflict with Israel not merely as a political battle but as a religious and moral obligation, linking Lebanon’s quest for autonomy with the Shia tradition of resisting injustice. This approach allowed Hezbollah to merge its military actions with a broader cultural identity, resonating across both historical and religious dimensions.

Hezbollah's evolution from a guerrilla force to a quasi-state actor involved more than just military expansion or political participation. Its infrastructure has not only filled the gaps left by the Lebanese state but has actively competed with and undermined the government to assert its dominance. By the early 2000s, Hezbollah had embedded itself in Lebanon’s political system, securing key ministerial positions and forming alliances with major political parties, including the Christian Free Patriotic Movement led by Michel Aoun. These alliances marked a significant shift in Lebanon’s sectarian dynamics, as it was the first time a Shia party gained the support of a major Christian faction, expanding Hezbollah's political legitimacy beyond its Shia base. This legitimacy enabled Hezbollah to strengthen its influence over state institutions, including the Lebanese Armed Forces and the Ministry of Telecommunications, granting access to critical national infrastructure.

Hezbollah’s state-building strategy involves Sharia courts, operating alongside Lebanon's national judiciary, playing a crucial role in controlling the Shia population in southern Lebanon. These courts handle civil disputes, family law, and even criminal cases within the framework of Islamic jurisprudence, offering an alternative to the secular legal system. This parallel judiciary reinforces Hezbollah’s ideological legitimacy as the guardian of Shia Islamic values while providing services that the state cannot or will not offer, especially in rural areas where government presence is minimal and Hezbollah’s influence dominates.

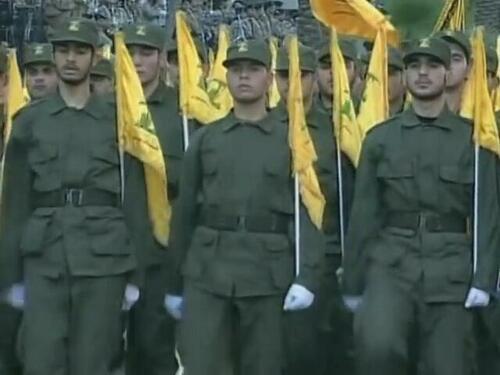

Hezbollah also uses commemorations as a powerful tool for political mobilization and social cohesion. Ashura, the annual Shia ritual mourning Imam Hussein’s martyrdom, holds deep symbolic significance. Hezbollah has repurposed it to strengthen its narrative of resistance, organizing large public demonstrations where Nasrallah delivers speeches drawing parallels between Hussein's martyrdom and Hezbollah’s struggle against Israel. These events, while religious in origin, are highly political, serving as both a rallying point for supporters and a demonstration of Hezbollah’s ability to mobilize large segments of the population.

In an effort to unite different factions under a broader nationalist identity, Hezbollah has made subtle but significant appeals to Lebanon’s ancient Phoenician heritage. Traditionally embraced by Maronites, Hezbollah has strategically invoked Phoenician identity to appeal to Lebanese Christians and secular nationalists wary of its Islamist roots.

Hezbollah often references Lebanon’s ancient maritime heritage in speeches and cultural events, portraying itself as the inheritor of a legacy of resistance to foreign domination. This blending of Phoenician and Islamic identities acts as a form of cultural diplomacy, positioning Hezbollah as a defender of all Lebanese, beyond sectarian lines. Control over key archaeological sites, like the ruins at Tyre and the temples at Baalbek, further integrates this narrative into its political strategy, solidifying Hezbollah’s role as a guardian of Lebanon’s cultural legacy.

While Hezbollah is often perceived as a monolithic organization, there are significant, underexplored tensions within its leadership, particularly between its military commanders and the religious clerics who provide its ideological and theological legitimacy. Hezbollah’s formal allegiance to the doctrine of wilayat al-faqih (the guardianship of the Islamic jurist), which binds it to the authority of Iran’s Supreme Leader, creates a unique dynamic that does not always align with the local religious authority of Lebanon’s Shia clerics.

In southern Lebanon, clerical authority has traditionally been fragmented, with multiple maraji (sources of emulation) influencing the Shia population. Before Hezbollah’s rise, many Lebanese Shia followed clerics who were either neutral or opposed to the doctrine of wilayat al-faqih, including the followers of Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Hussein Fadlallah. Fadlallah, a prominent Lebanese cleric with significant influence in Beirut and southern Lebanon, supported the resistance movement but advocated for a more independent Shia political theology that did not place Lebanon’s Shia community under the direct control of Iranian clerics.

Hezbollah’s rise, with its explicit allegiance to Iranian clerical authority, quietly created significant tensions within the Lebanese Shia religious community. These tensions became particularly evident in the 1990s when several key clerics, including those aligned with Fadlallah, voiced concerns about Hezbollah’s growing power and its subordination to Tehran. Although Hezbollah publicly expressed respect for Fadlallah, it effectively marginalized his influence, especially in political decision-making. This subtle power struggle remains largely hidden from public view but is crucial to understanding the internal complexities of Hezbollah’s religious authority.

The relationship between Hezbollah’s leadership and Lebanon’s local Shia clerics is further complicated by the group’s military ambitions. While Hezbollah’s clerical supporters in Iran, particularly Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, have consistently endorsed military action against Israel, some Lebanese clerics have expressed reservations about the long-term costs of ongoing conflict. During the 2006 war with Israel, reports—rarely discussed publicly—indicated that several prominent Shia clerics privately questioned the wisdom of continuing the war, particularly given the widespread destruction it caused in southern Lebanon’s Shia villages.

This tension between local religious authorities and Hezbollah’s military leadership reflects a broader struggle within the Shia community over the future direction of the resistance. While Hezbollah’s public face remains unified, these internal fissures over religious authority and military strategy could have significant implications for the group’s future, particularly if local clerics begin to assert a more independent line.

Hezbollah's rise and consolidation of power in southern Lebanon can be largely attributed to its strategic use of traditional clan and family networks (hamulas). In rural areas like southern Lebanon, Lebanese society remains deeply organized around familial and clan-based allegiances, which have historically shaped local political dynamics. Hezbollah’s ability to navigate and, in some cases, co-opt these powerful networks has been crucial to its success in establishing itself as more than just a political or military movement.

Southern Lebanon’s Shia clans, some tracing their ancestry back centuries, often acted as local power brokers in the absence of strong state governance, particularly during the Ottoman and French Mandate periods. Clans such as the Bazzi, Haidar, and Moussawi wield significant influence in their territories, often determining the outcome of local elections and resolving disputes. While these clans had traditionally been neutral or aligned with other Lebanese factions, Hezbollah’s leadership recognized early on that integrating—or at least securing the neutrality of—these networks would be vital for controlling the region.

Hezbollah’s outreach to these clans was not purely political but also strategic. The group offered economic incentives, protection, and integration into its organizational structure in exchange for loyalty. For example, by placing clan leaders in influential positions within Hezbollah’s social service networks, such as the Jihad al-Bina reconstruction organization, Hezbollah ensured its reach extended into the deeply rooted clan systems. This allowed Hezbollah to leverage these networks for recruitment and intelligence gathering while maintaining an appearance of local autonomy.

However, this relationship has not always been without conflict. Hezbollah’s rise often displaced traditional clan power structures, particularly when it came to control over smuggling routes and agricultural lands. In the early 1990s, there were several instances of violent clashes between Hezbollah fighters and clan militias over control of key trade routes used for smuggling goods across the Lebanese-Syrian border. While these clashes rarely made international headlines, they were significant in shaping Hezbollah’s long-term strategy of integrating rather than overtly dominating clan networks. By the late 1990s, most of these clans had either been absorbed into Hezbollah’s broader structure or neutralized through a combination of political maneuvering and economic inducements.

Read the rest here...

Authored by Carlo J.V. Caro via RealClearDefense,

Unlike many movements that adopt the mantle of liberation for political gain, Hezbollah’s portrayal as a liberating force is tied to a long-standing cultural memory of foreign oppression, from the Ottoman Empire to the French Mandate. Understanding how Hezbollah leveraged this identity requires an examination of Lebanon’s history of local resistance, which was not always violent but often manifested as passive defiance, economic self-sufficiency, and cultural preservation, especially among marginalized Shia agrarian communities.

During the Ottoman era, southern Lebanon’s Shia population was systematically neglected and excluded by the ruling class, which favored the Sunni elite and Christian coastal merchants. Ottoman tax farmers exploited Shia agricultural communities in the Bekaa Valley and southern Lebanon, fostering deep resentment toward external governance. The Shia community’s refusal to pay taxes or serve in the Ottoman military, a resistance that subtly persisted under the French Mandate, reinforced their self-perception as an oppressed yet resilient group. Though largely nonviolent, this resistance cultivated a cultural aversion to foreign control, which Hezbollah later capitalized on.

In contrast, Mount Lebanon operated under a semi-autonomous Mutasarrifate system, allowing Druze and Maronite elites to negotiate governance with the Ottomans—an advantage not extended to the Shia of southern Lebanon. While Maronites and Druze enjoyed self-governance and strong trade ties with European powers, the Shia were relegated to peripheral roles, fostering isolation and mistrust toward both central authorities and foreign powers. This fragmented Lebanese identity, with allegiance often directed toward local feudal lords or religious leaders, persisted into the post-Ottoman period, worsened by the French Mandate’s efforts to centralize control in Beirut, further marginalizing southern Lebanon.

When the French assumed control of Lebanon after World War I, they introduced modern institutions but often at the expense of local autonomy, particularly in rural areas. While infrastructure development flourished in Beirut and other urban centers, the agrarian Shia south was largely neglected, reinforcing economic isolation and discontent. The French also shaped Lebanon’s political system to the detriment of the Shia. The Confessionalist system they implemented ensured minimal political representation for the Shia, who were overshadowed by Maronite Christians and Sunni Muslims. This marginalization persisted after independence, reaching a breaking point during the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990). Shia exclusion from economic and political power became a critical factor in Hezbollah’s rise, as it united the community under its banner. The political system, rooted in colonialism, fueled Hezbollah’s anti-colonial narrative, allowing it to position itself as the true heir to Lebanon’s liberation struggles.

Hezbollah effectively co-opted the Shia principle of sabr (steadfastness), a deeply ingrained religious and cultural value stemming from the martyrdom of Imam Hussein at Karbala in 680 CE. The theme of enduring suffering and injustice while remaining resolute became central to Hezbollah’s narrative, aligning with both the historical experience of foreign oppression and the contemporary struggles of Lebanese Shia. When Hezbollah claimed responsibility for Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000, it framed the event as a validation of the Shia legacy of perseverance, demonstrating that victory could be achieved through unwavering resistance.

Hezbollah further reinforced this narrative by invoking the concept of muwajaha (confrontation), a term in Shia tradition closely tied to the symbolic power of Karbala. In southern Lebanon, muwajaha extends beyond military struggle to encompass the religious and cultural duty to resist oppression. Hassan Nasrallah consistently framed the conflict with Israel not merely as a political battle but as a religious and moral obligation, linking Lebanon’s quest for autonomy with the Shia tradition of resisting injustice. This approach allowed Hezbollah to merge its military actions with a broader cultural identity, resonating across both historical and religious dimensions.

Hezbollah’s evolution from a guerrilla force to a quasi-state actor involved more than just military expansion or political participation. Its infrastructure has not only filled the gaps left by the Lebanese state but has actively competed with and undermined the government to assert its dominance. By the early 2000s, Hezbollah had embedded itself in Lebanon’s political system, securing key ministerial positions and forming alliances with major political parties, including the Christian Free Patriotic Movement led by Michel Aoun. These alliances marked a significant shift in Lebanon’s sectarian dynamics, as it was the first time a Shia party gained the support of a major Christian faction, expanding Hezbollah’s political legitimacy beyond its Shia base. This legitimacy enabled Hezbollah to strengthen its influence over state institutions, including the Lebanese Armed Forces and the Ministry of Telecommunications, granting access to critical national infrastructure.

Hezbollah’s state-building strategy involves Sharia courts, operating alongside Lebanon’s national judiciary, playing a crucial role in controlling the Shia population in southern Lebanon. These courts handle civil disputes, family law, and even criminal cases within the framework of Islamic jurisprudence, offering an alternative to the secular legal system. This parallel judiciary reinforces Hezbollah’s ideological legitimacy as the guardian of Shia Islamic values while providing services that the state cannot or will not offer, especially in rural areas where government presence is minimal and Hezbollah’s influence dominates.

Hezbollah also uses commemorations as a powerful tool for political mobilization and social cohesion. Ashura, the annual Shia ritual mourning Imam Hussein’s martyrdom, holds deep symbolic significance. Hezbollah has repurposed it to strengthen its narrative of resistance, organizing large public demonstrations where Nasrallah delivers speeches drawing parallels between Hussein’s martyrdom and Hezbollah’s struggle against Israel. These events, while religious in origin, are highly political, serving as both a rallying point for supporters and a demonstration of Hezbollah’s ability to mobilize large segments of the population.

In an effort to unite different factions under a broader nationalist identity, Hezbollah has made subtle but significant appeals to Lebanon’s ancient Phoenician heritage. Traditionally embraced by Maronites, Hezbollah has strategically invoked Phoenician identity to appeal to Lebanese Christians and secular nationalists wary of its Islamist roots.

Hezbollah often references Lebanon’s ancient maritime heritage in speeches and cultural events, portraying itself as the inheritor of a legacy of resistance to foreign domination. This blending of Phoenician and Islamic identities acts as a form of cultural diplomacy, positioning Hezbollah as a defender of all Lebanese, beyond sectarian lines. Control over key archaeological sites, like the ruins at Tyre and the temples at Baalbek, further integrates this narrative into its political strategy, solidifying Hezbollah’s role as a guardian of Lebanon’s cultural legacy.

While Hezbollah is often perceived as a monolithic organization, there are significant, underexplored tensions within its leadership, particularly between its military commanders and the religious clerics who provide its ideological and theological legitimacy. Hezbollah’s formal allegiance to the doctrine of wilayat al-faqih (the guardianship of the Islamic jurist), which binds it to the authority of Iran’s Supreme Leader, creates a unique dynamic that does not always align with the local religious authority of Lebanon’s Shia clerics.

In southern Lebanon, clerical authority has traditionally been fragmented, with multiple maraji (sources of emulation) influencing the Shia population. Before Hezbollah’s rise, many Lebanese Shia followed clerics who were either neutral or opposed to the doctrine of wilayat al-faqih, including the followers of Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Hussein Fadlallah. Fadlallah, a prominent Lebanese cleric with significant influence in Beirut and southern Lebanon, supported the resistance movement but advocated for a more independent Shia political theology that did not place Lebanon’s Shia community under the direct control of Iranian clerics.

Hezbollah’s rise, with its explicit allegiance to Iranian clerical authority, quietly created significant tensions within the Lebanese Shia religious community. These tensions became particularly evident in the 1990s when several key clerics, including those aligned with Fadlallah, voiced concerns about Hezbollah’s growing power and its subordination to Tehran. Although Hezbollah publicly expressed respect for Fadlallah, it effectively marginalized his influence, especially in political decision-making. This subtle power struggle remains largely hidden from public view but is crucial to understanding the internal complexities of Hezbollah’s religious authority.

The relationship between Hezbollah’s leadership and Lebanon’s local Shia clerics is further complicated by the group’s military ambitions. While Hezbollah’s clerical supporters in Iran, particularly Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, have consistently endorsed military action against Israel, some Lebanese clerics have expressed reservations about the long-term costs of ongoing conflict. During the 2006 war with Israel, reports—rarely discussed publicly—indicated that several prominent Shia clerics privately questioned the wisdom of continuing the war, particularly given the widespread destruction it caused in southern Lebanon’s Shia villages.

This tension between local religious authorities and Hezbollah’s military leadership reflects a broader struggle within the Shia community over the future direction of the resistance. While Hezbollah’s public face remains unified, these internal fissures over religious authority and military strategy could have significant implications for the group’s future, particularly if local clerics begin to assert a more independent line.

Hezbollah’s rise and consolidation of power in southern Lebanon can be largely attributed to its strategic use of traditional clan and family networks (hamulas). In rural areas like southern Lebanon, Lebanese society remains deeply organized around familial and clan-based allegiances, which have historically shaped local political dynamics. Hezbollah’s ability to navigate and, in some cases, co-opt these powerful networks has been crucial to its success in establishing itself as more than just a political or military movement.

Southern Lebanon’s Shia clans, some tracing their ancestry back centuries, often acted as local power brokers in the absence of strong state governance, particularly during the Ottoman and French Mandate periods. Clans such as the Bazzi, Haidar, and Moussawi wield significant influence in their territories, often determining the outcome of local elections and resolving disputes. While these clans had traditionally been neutral or aligned with other Lebanese factions, Hezbollah’s leadership recognized early on that integrating—or at least securing the neutrality of—these networks would be vital for controlling the region.

Hezbollah’s outreach to these clans was not purely political but also strategic. The group offered economic incentives, protection, and integration into its organizational structure in exchange for loyalty. For example, by placing clan leaders in influential positions within Hezbollah’s social service networks, such as the Jihad al-Bina reconstruction organization, Hezbollah ensured its reach extended into the deeply rooted clan systems. This allowed Hezbollah to leverage these networks for recruitment and intelligence gathering while maintaining an appearance of local autonomy.

However, this relationship has not always been without conflict. Hezbollah’s rise often displaced traditional clan power structures, particularly when it came to control over smuggling routes and agricultural lands. In the early 1990s, there were several instances of violent clashes between Hezbollah fighters and clan militias over control of key trade routes used for smuggling goods across the Lebanese-Syrian border. While these clashes rarely made international headlines, they were significant in shaping Hezbollah’s long-term strategy of integrating rather than overtly dominating clan networks. By the late 1990s, most of these clans had either been absorbed into Hezbollah’s broader structure or neutralized through a combination of political maneuvering and economic inducements.

Read the rest here…

Loading…