By Stefan Koopman, Senior Macro Strategist at Rabobank

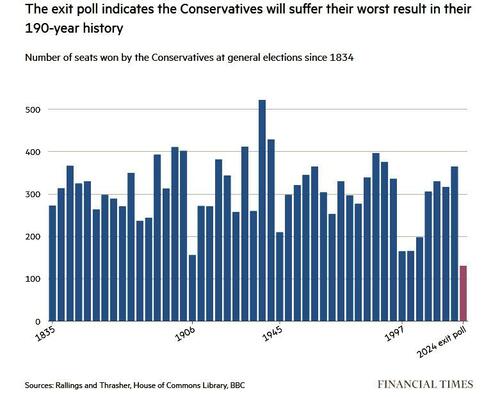

To no one’s surprise, Labour won the UK election. Less than five years after Boris Johnson’s decisive win over Jeremy Corbyn, the Conservatives experienced their worst defeat in history.

Constituencies that were once considered secure Tory bastions have turned away from them. At the same time, a surge of smaller parties and independents has created a complex and divided political landscape. Indeed, Labour’s victory looks to be largely driven by a widespread desire to oust the Tories rather than a strong endorsement of its own policies. Nonetheless, Keir Starmer’s efforts to make Labour electable again after the years of Corbyn have worked out in their favour. In less than five years, he has restored trust in Labour on a number of key issues, including fiscal policy.

With 34% of the vote, Labour looks to have secured almost 64% of the 650 seats in the UK parliament. It’s clear they understood the central truth of the British electoral system: the popular vote is less important than the geographic distribution of the vote. The Tories, ending up at just c. 120 seats, warn that such a “super majority” would give Starmer’s Labour unchecked power. It is, however, important to note that the UK has no such thing as a super majority. Parliament is sovereign and can enact any legislation through the normal legislative process, regardless of whether the majority is 10 or 200. Britain has no special categories of legislation beyond the reach of a regular majority and even then, a simple majority would suffice to scrap such legislation. The real issues lie in the over-empowerment of the executive, the lack of constitutional checks and balances, and the distortions caused by the electoral system. However, a majority is a majority.

That said, landslides like this can be risky, with potential opposition emerging from within an overly large parliamentary party. Many Labour MPs will have little hope of promotion due to the limited number of government positions available, and numerous junior MPs will likely realize they are at high risk of losing their seats in 2028/29. This outcome is unlikely to be repeated. Labour has secured such a broad and geographically efficient vote that maintaining this coalition of voters seems impossible. At the constituency level, seats are tighter than at any point since 1945. This could lead to policy inertia, especially given Starmer’s cautious and calculated approach. This, we think, may also limit significant progress on EU-UK trade relations.

Labour mostly looks inward when it tries to tackle the pressing issue of economic growth. The current planning system, which allows local communities to block development, has hindered the construction of much-needed housing and infrastructure and is up for deep reform. Labour now has the parliamentary majority to do so, but the relatively slim majorities on a constituency level suggest that there is not as much political headroom as some polls have suggested.

Despite its plans to boost economic growth through political stability and expedited investment, growth may not come quickly enough to avoid difficult fiscal decisions. The pressure on real departmental spending is already very high, as the Tories had postponed many tough decisions to a post-election Budget, knowing they were likely to lose the election and thus not have to own these cuts. As the population ages, many budgetary choices will become more challenging, not easier. This makes it hard to envision Labour making cuts to balance the books and meet the rule that debt should be declining as a share of national income after five years. Consequently, it will be difficult to achieve Labour’s ambitious goals, including reducing NHS waiting lists and hiring more public sector workers, without raising taxes or changing the fiscal rules.

However, the shadow of Liz Truss – who has lost her seat – still looms over Westminster. Her policies of unfunded tax cuts are not ones that other politicians want to be associated with. Shadow Chancellor Reeves has emphasised the importance of market-friendly and prudent budget management and has been reluctant to discuss any changes to the fiscal rules. It’s also why this election was, from the market’s perspective, a non-event. A lot of water will flow through the Thames before politicians in Westminster dare to take bold fiscal action. Eventually, however, this will become inevitable to lift the UK out of its low-productivity, low-growth quagmire.

By Stefan Koopman, Senior Macro Strategist at Rabobank

To no one’s surprise, Labour won the UK election. Less than five years after Boris Johnson’s decisive win over Jeremy Corbyn, the Conservatives experienced their worst defeat in history.

Constituencies that were once considered secure Tory bastions have turned away from them. At the same time, a surge of smaller parties and independents has created a complex and divided political landscape. Indeed, Labour’s victory looks to be largely driven by a widespread desire to oust the Tories rather than a strong endorsement of its own policies. Nonetheless, Keir Starmer’s efforts to make Labour electable again after the years of Corbyn have worked out in their favour. In less than five years, he has restored trust in Labour on a number of key issues, including fiscal policy.

With 34% of the vote, Labour looks to have secured almost 64% of the 650 seats in the UK parliament. It’s clear they understood the central truth of the British electoral system: the popular vote is less important than the geographic distribution of the vote. The Tories, ending up at just c. 120 seats, warn that such a “super majority” would give Starmer’s Labour unchecked power. It is, however, important to note that the UK has no such thing as a super majority. Parliament is sovereign and can enact any legislation through the normal legislative process, regardless of whether the majority is 10 or 200. Britain has no special categories of legislation beyond the reach of a regular majority and even then, a simple majority would suffice to scrap such legislation. The real issues lie in the over-empowerment of the executive, the lack of constitutional checks and balances, and the distortions caused by the electoral system. However, a majority is a majority.

That said, landslides like this can be risky, with potential opposition emerging from within an overly large parliamentary party. Many Labour MPs will have little hope of promotion due to the limited number of government positions available, and numerous junior MPs will likely realize they are at high risk of losing their seats in 2028/29. This outcome is unlikely to be repeated. Labour has secured such a broad and geographically efficient vote that maintaining this coalition of voters seems impossible. At the constituency level, seats are tighter than at any point since 1945. This could lead to policy inertia, especially given Starmer’s cautious and calculated approach. This, we think, may also limit significant progress on EU-UK trade relations.

Labour mostly looks inward when it tries to tackle the pressing issue of economic growth. The current planning system, which allows local communities to block development, has hindered the construction of much-needed housing and infrastructure and is up for deep reform. Labour now has the parliamentary majority to do so, but the relatively slim majorities on a constituency level suggest that there is not as much political headroom as some polls have suggested.

Despite its plans to boost economic growth through political stability and expedited investment, growth may not come quickly enough to avoid difficult fiscal decisions. The pressure on real departmental spending is already very high, as the Tories had postponed many tough decisions to a post-election Budget, knowing they were likely to lose the election and thus not have to own these cuts. As the population ages, many budgetary choices will become more challenging, not easier. This makes it hard to envision Labour making cuts to balance the books and meet the rule that debt should be declining as a share of national income after five years. Consequently, it will be difficult to achieve Labour’s ambitious goals, including reducing NHS waiting lists and hiring more public sector workers, without raising taxes or changing the fiscal rules.

However, the shadow of Liz Truss – who has lost her seat – still looms over Westminster. Her policies of unfunded tax cuts are not ones that other politicians want to be associated with. Shadow Chancellor Reeves has emphasised the importance of market-friendly and prudent budget management and has been reluctant to discuss any changes to the fiscal rules. It’s also why this election was, from the market’s perspective, a non-event. A lot of water will flow through the Thames before politicians in Westminster dare to take bold fiscal action. Eventually, however, this will become inevitable to lift the UK out of its low-productivity, low-growth quagmire.

Loading…