Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

If we want social / economic renewal, we have to make it straightforward for anyone willing to adopt the values and habits of "thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work" to climb the ladder to middle class security.

How easy is it to climb the social mobility ladder into the middle class? It's a key question because the middle class is the ultimate source of social stability, innovation and democracy.

To answer this question, we must start with the rise of the middle class in Europe and the market economy which enabled that rise.

This article explores the specific cultural adaptations which set the stage for Europe's adoption of a market economy as the primary social-economic force, supplanting family and feudal ties.

When did Europe pull ahead? And why?

The author notes that Northern European economic expansion began in the 1300s, before the Protestant Reformation, the discovery of the Americas and before the printing press--all factors others have identified as key to Europe's rise to dominance.

He identifies the assimilation by Catholic Europe of two Northern European cultural traits--individualism and the ban on cousin marriages, which led to social trust extending beyond the immediate family-- as critical preconditions for the acceptance of a market economy.

He then adds a third condition: the suppression / elimination of violent males from the social order via harsh secular and religious punishment of evil-doers. Murder rates declined as the most violent were executed or imprisoned in large numbers.

Here are some key excerpts from the article:

"Those three causes--individualism, impersonal sociality, and a pacified environment--allowed the market economy to grow beyond its former limits.

'The Market' could thus spread farther and farther beyond the marketplace, replacing older forms of exchange and ultimately replacing kinship as the main organizing principle of society.

The English as a whole became more and more middle-class in their mindset: 'Thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work were becoming values for communities that previously had been spendthrift, impulsive, violent, and leisure loving.'

The Western world thus embarked on a trajectory of sustained economic growth. This is in contrast to what we see in other times and places, where economic growth tended to stall after a while and give way to stagnation or even contraction.

Western Christianity (which assimilated pagan characteristics of northern Europe) enabled 'the peace, order, and stability that allowed the middle class to expand and become dominant.'" (end of excerpt)

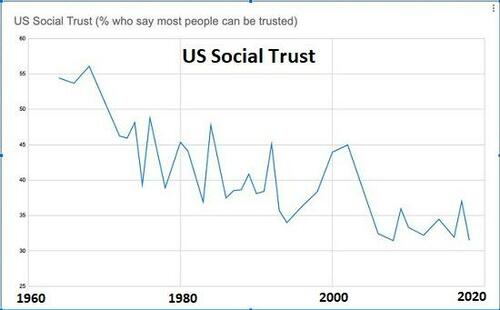

I am wary of relying on any limited set of reasons for Europe's rise, but the social willingness to trust strangers is a largely overlooked factor in stable, prosperous societies.

Modern-day surveys find that Scandinavian people tend to have high levels of trust in strangers, and this correlates to high levels of general prosperity and individual happiness.

Clearly, economies in which business is only conducted with family members or equally narrow circles is far more limiting than economies in which business is conducted with strangers and impersonal corporations.

As people acquired means, they could afford more education, and they had a stake in the system that needed to be defended / advocated. This advocacy nurtured democratic / legal institutions and a free press. These institutional forms of social capital act as social technologies, enabling and nurturing the rise of markets, ownership of land and enterprises and the middle class.

Some of these critical social technologies stretch back to the Roman Era. These forms of social capital were lost to feudalism, and their restoration in the 1300s and 1400s enabled the rise of a middle class that was neither nobility nor serf.

As the book The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages 400-1000 detailed, the egalitarian aspects of Roman rule continued to influence everyday life for hundreds of years. It took centuries for feudalism to eradicate these holdovers from Roman rule (for example, peasant ownership of land).

The rise of the middle class broke the stranglehold of feudalism by encouraging free movement of labor and capital, and strengthening weak central governments to the point that feudal fiefdoms answered to the central government again, as in the Roman and Carolingian eras.

In my view, the key factor that determines the rise of a middle class is the relative ease of laborers achieving middle class ownership, security and stability.

In the classical Roman era, freed slaves often ended up doing very well for themselves and becoming middle class, as the class boundaries were porous enough to enable craftworkers and small merchants to improve their lot in life.

In the context of this article, are "thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work" enough to transform a family from penury to middle class? If the answer is "yes," then the ladder to middle class security is open to anyone who adopts these values / habits.

If the answer is "no," then the ladder to middle class security is not open to everyone, and the economy stagnates.

Broadly speaking, virtually anyone who rigorously adopted "thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work" in the fifty years from 1946 to 1995 could (once they married and gained a two-income household) eventually afford a family and a stake in the system--a house and/or small business, a pension, etc.

Once financialization and globalization rose to dominance and distorted the economy with increasing wealth and income inequality ("winner take most"), this was no longer the case.

Workers of average skill, motivation and wages who adopt "thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work" can no longer afford a family or a stake in the system--at least in high-cost, enormously unequal locales.

This is true not just of the U.S. but globally.

This reality has fueled two trends of decay: 1) a dependence on speculation as the only means to "get ahead" and 2) "laying flat" / "let it rot"--giving up on marrying, having a family and acquiring a stake in the system.

Once these aspirations are only available to those with the right connections or extraordinary drive / talent, society and the economy decay and collapse under the weight of inequality--an inequality defended by those who made it to the top and want to preserve the status quo as it is.

This is the pattern of stagnation and collapse: once the elites devote themselves to suppressing adaptations and defending extremes of the wealth-income-power inequality that benefits them, the system decays and collapses.

The top 10% want the status quo to continue as is, even as the bottom 90% fall behind. When enough of the bottom 90% decide to "let it rot," the entire rotten structure collapses under its own weight.

If we want social / economic renewal, we have to make it straightforward for anyone willing to adopt the values and habits of "thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work" to climb the ladder to middle class security.

Trust matters, too. A middle class can only thrive if the institutions enabling social technologies are trustworthy, and others in the markets of labor, capital, goods, services and risk are trustworthy. Once social trust is lost, the foundations of society and the economy crumble.

* * *

Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

If we want social / economic renewal, we have to make it straightforward for anyone willing to adopt the values and habits of “thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work” to climb the ladder to middle class security.

How easy is it to climb the social mobility ladder into the middle class? It’s a key question because the middle class is the ultimate source of social stability, innovation and democracy.

To answer this question, we must start with the rise of the middle class in Europe and the market economy which enabled that rise.

This article explores the specific cultural adaptations which set the stage for Europe’s adoption of a market economy as the primary social-economic force, supplanting family and feudal ties.

When did Europe pull ahead? And why?

The author notes that Northern European economic expansion began in the 1300s, before the Protestant Reformation, the discovery of the Americas and before the printing press–all factors others have identified as key to Europe’s rise to dominance.

He identifies the assimilation by Catholic Europe of two Northern European cultural traits–individualism and the ban on cousin marriages, which led to social trust extending beyond the immediate family– as critical preconditions for the acceptance of a market economy.

He then adds a third condition: the suppression / elimination of violent males from the social order via harsh secular and religious punishment of evil-doers. Murder rates declined as the most violent were executed or imprisoned in large numbers.

Here are some key excerpts from the article:

“Those three causes–individualism, impersonal sociality, and a pacified environment–allowed the market economy to grow beyond its former limits.

‘The Market’ could thus spread farther and farther beyond the marketplace, replacing older forms of exchange and ultimately replacing kinship as the main organizing principle of society.

The English as a whole became more and more middle-class in their mindset: ‘Thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work were becoming values for communities that previously had been spendthrift, impulsive, violent, and leisure loving.’

The Western world thus embarked on a trajectory of sustained economic growth. This is in contrast to what we see in other times and places, where economic growth tended to stall after a while and give way to stagnation or even contraction.

Western Christianity (which assimilated pagan characteristics of northern Europe) enabled ‘the peace, order, and stability that allowed the middle class to expand and become dominant.'” (end of excerpt)

I am wary of relying on any limited set of reasons for Europe’s rise, but the social willingness to trust strangers is a largely overlooked factor in stable, prosperous societies.

Modern-day surveys find that Scandinavian people tend to have high levels of trust in strangers, and this correlates to high levels of general prosperity and individual happiness.

Clearly, economies in which business is only conducted with family members or equally narrow circles is far more limiting than economies in which business is conducted with strangers and impersonal corporations.

As people acquired means, they could afford more education, and they had a stake in the system that needed to be defended / advocated. This advocacy nurtured democratic / legal institutions and a free press. These institutional forms of social capital act as social technologies, enabling and nurturing the rise of markets, ownership of land and enterprises and the middle class.

Some of these critical social technologies stretch back to the Roman Era. These forms of social capital were lost to feudalism, and their restoration in the 1300s and 1400s enabled the rise of a middle class that was neither nobility nor serf.

As the book The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages 400-1000 detailed, the egalitarian aspects of Roman rule continued to influence everyday life for hundreds of years. It took centuries for feudalism to eradicate these holdovers from Roman rule (for example, peasant ownership of land).

The rise of the middle class broke the stranglehold of feudalism by encouraging free movement of labor and capital, and strengthening weak central governments to the point that feudal fiefdoms answered to the central government again, as in the Roman and Carolingian eras.

In my view, the key factor that determines the rise of a middle class is the relative ease of laborers achieving middle class ownership, security and stability.

In the classical Roman era, freed slaves often ended up doing very well for themselves and becoming middle class, as the class boundaries were porous enough to enable craftworkers and small merchants to improve their lot in life.

In the context of this article, are “thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work” enough to transform a family from penury to middle class? If the answer is “yes,” then the ladder to middle class security is open to anyone who adopts these values / habits.

If the answer is “no,” then the ladder to middle class security is not open to everyone, and the economy stagnates.

Broadly speaking, virtually anyone who rigorously adopted “thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work” in the fifty years from 1946 to 1995 could (once they married and gained a two-income household) eventually afford a family and a stake in the system–a house and/or small business, a pension, etc.

Once financialization and globalization rose to dominance and distorted the economy with increasing wealth and income inequality (“winner take most”), this was no longer the case.

Workers of average skill, motivation and wages who adopt “thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work” can no longer afford a family or a stake in the system–at least in high-cost, enormously unequal locales.

This is true not just of the U.S. but globally.

This reality has fueled two trends of decay: 1) a dependence on speculation as the only means to “get ahead” and 2) “laying flat” / “let it rot”–giving up on marrying, having a family and acquiring a stake in the system.

Once these aspirations are only available to those with the right connections or extraordinary drive / talent, society and the economy decay and collapse under the weight of inequality–an inequality defended by those who made it to the top and want to preserve the status quo as it is.

This is the pattern of stagnation and collapse: once the elites devote themselves to suppressing adaptations and defending extremes of the wealth-income-power inequality that benefits them, the system decays and collapses.

The top 10% want the status quo to continue as is, even as the bottom 90% fall behind. When enough of the bottom 90% decide to “let it rot,” the entire rotten structure collapses under its own weight.

If we want social / economic renewal, we have to make it straightforward for anyone willing to adopt the values and habits of “thrift, prudence, negotiation, and hard work” to climb the ladder to middle class security.

Trust matters, too. A middle class can only thrive if the institutions enabling social technologies are trustworthy, and others in the markets of labor, capital, goods, services and risk are trustworthy. Once social trust is lost, the foundations of society and the economy crumble.

* * *

Loading…