With inflation coming in red hot, hotter than most had anticipated, and unlikely to revert back to normal any time soon especially as exploding energy, food and rent prices will remain in the stratosphere for a long time (absent a depression), the last hope bulls have is that the jobs market will crater (a process which real-time indicators suggest is already in pla, yet which the BLS stubbornly refuses to acknowledge, likely for obvious political reasons with a critical mid-term election looming).

And if not crater, then certainly the US labor market needs to slow down well beyond recent trendline in order to short-circuit the vicious wage-price spiral and allow inflation to reset. Indeed, as Goldman's chief economist Jan Hatzius said on Friday, a combination of higher labor force participation and lower labor demand will likely be necessary to restore balance to the labor market and bring inflation back toward the FOMC’s 2% inflation target.

To be sure, indicators of labor demand have already softened in recent months, with job openings declining 4% in April and the monthly pace of payroll growth slowing to roughly 400k from 600k in the winter, but as even the most optimistic economists will admit, demand needs to cool meaningfully further (in fact, as even Bloomberg now admits, "Powell Facing Choice Between Elevated US Inflation and Recession.")

So doing some quick math, Goldman calculates that payroll growth will need to slow to roughly 150k on average in the second half of the year in order to begin to rebalance the labor market and calm wage and price pressures, and the faster the better. The problem is that as Goldman also concedes, according to historical data and statistical analysis "such a slowdown may be hard to achieve: slowdowns of this magnitude have only happened a few of times outside of recessions in modern US history, and while the recent trend of payrolls growth—the best predictor of upcoming payrolls growth—has slowed, the pace is still elevated."

Here are some more details on why the hurdle for job growth to slow by the required amount appears high on a historical basis..

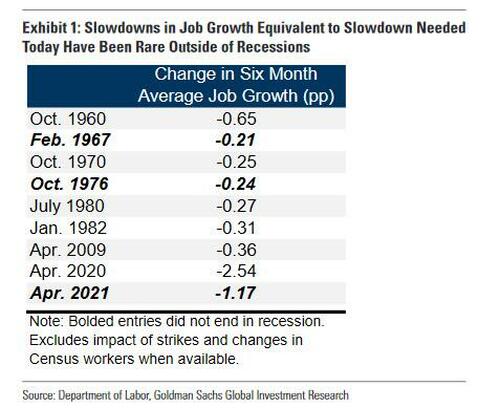

The chart below shows the nine instances since 1960 that payrolls growth has slowed by more than 0.20% — roughly the amount Goldman thinks is required to restore balance to the labor market today, expressed as the change in the six-month average monthly percent change (in Goldman's framework, monthly payroll growth needs to decline from 0.34% over the last six months to 0.11% over the next six months).

Although slowdowns of 0.20% or more have been quite uncommon outside of recessions, today’s economic backdrop - at least until a recession is officially declared in a few months - is somewhat comparable to the three historical instances where job growth slowed and a recession was avoided: ahead of the slowdowns in 1976 and 2021, job growth was running well above trend as the economy was recovering from a recession, and ahead of the slowdown in 1967, the Federal Reserve tightened monetary policy to combat inflationary pressures.

As an aside, Goldman economists points out that the recent pace of payroll growth is one of the best predictors of upcoming payrolls growth and even more useful than knowing the future rate of output growth (the predictive power of job momentum likely reflects lags in the hiring and firing process, the cost of large personnel changes, and the pro-cyclicality of capacity utilization.)

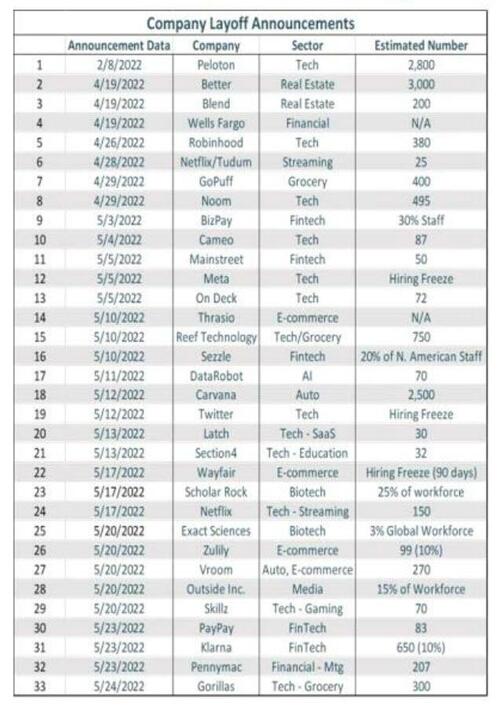

With payrolls growing just over 400k per month over the last three months (if slowing), putting a high weight on momentum would suggest a high hurdle for job growth to slow enough in coming quarters to restore balance to the labor market. However, it is also the case that employment growth has recently slowed to roughly 225k per month over the last three months in the noisier household survey, suggesting that the underlying trend could be overstated by just looking at nonfarm payrolls. Furthermore, while not captured yet by the US labor bureau, leading labor market indicators such as mass layoff announcement has surged in recent weeks, with dozens of announcements in the otherwise rock-solid tech sector. Expect similar weakness across the rest of the rest of the labor market.

Goldman itself admits as much: "recent anecdotes of hiring freezes and more selective hiring indicate that companies expect payroll growth to slow, and the most recent business activity surveys corroborate these signals."

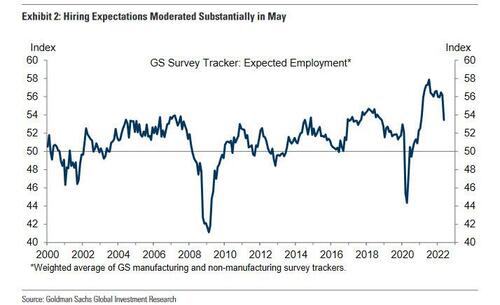

In the next chart, the bank constructs an aggregate index of employment growth expectations by replicating its own survey tracker methodology on the employment expectations components of eight regional Fed manufacturing and services surveys. It found that in May, this series recorded its third largest monthly decline since 2000—behind only October 2008 and March 2020—yet even so it remains at a historically elevated level... but not for long.

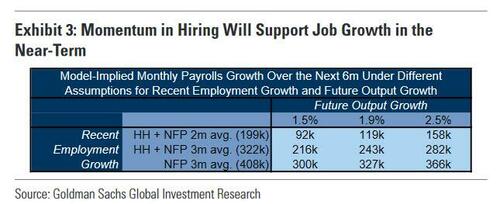

Which brings us to punchline #1: to get a sense of how much employment growth could slow - or rather should slow - over the coming months, Goldman estimates a model of future payroll growth based on lagged payroll growth, changes in output growth, and lagged changes in survey-based employment growth expectations. It then uses the model coefficients to project future payrolls growth based on different assumptions about the recent employment growth trend and future output growth.

Goldman derives two conclusions from the scenarios above:

- First, different plausible assumptions for the recent employment growth trend imply a wide range of outcomes for future payrolls growth: coupling the bank's baseline (and recently cut) H2 2002 GDP growth forecast with the different employment growth trends suggests that monthly payrolls growth could range from roughly 125k up to 325k (middle column).

- Second, the balance of risks to near-term employment growth appears skewed to the upside relative to Goldman's own forecasts of 215k per month over the next three months and 160k over the next six months (suggesting that Goldman is once again overly optimistic on the economy and will soon be slashing its jobs, and GDP, forecasts again).

One final point: while Goldman does not say it, but is generously implied in its analysis, the bigger the recession, the faster US job growth turns negative and the quicker wage growth implodes, the better for the bulls even if it sends the odds of more summer violence (if not before the midterms, then certainly next year after the GOP has won control of Congress) through the roof.

With inflation coming in red hot, hotter than most had anticipated, and unlikely to revert back to normal any time soon especially as exploding energy, food and rent prices will remain in the stratosphere for a long time (absent a depression), the last hope bulls have is that the jobs market will crater (a process which real-time indicators suggest is already in pla, yet which the BLS stubbornly refuses to acknowledge, likely for obvious political reasons with a critical mid-term election looming).

And if not crater, then certainly the US labor market needs to slow down well beyond recent trendline in order to short-circuit the vicious wage-price spiral and allow inflation to reset. Indeed, as Goldman’s chief economist Jan Hatzius said on Friday, a combination of higher labor force participation and lower labor demand will likely be necessary to restore balance to the labor market and bring inflation back toward the FOMC’s 2% inflation target.

To be sure, indicators of labor demand have already softened in recent months, with job openings declining 4% in April and the monthly pace of payroll growth slowing to roughly 400k from 600k in the winter, but as even the most optimistic economists will admit, demand needs to cool meaningfully further (in fact, as even Bloomberg now admits, “Powell Facing Choice Between Elevated US Inflation and Recession.”)

So doing some quick math, Goldman calculates that payroll growth will need to slow to roughly 150k on average in the second half of the year in order to begin to rebalance the labor market and calm wage and price pressures, and the faster the better. The problem is that as Goldman also concedes, according to historical data and statistical analysis “such a slowdown may be hard to achieve: slowdowns of this magnitude have only happened a few of times outside of recessions in modern US history, and while the recent trend of payrolls growth—the best predictor of upcoming payrolls growth—has slowed, the pace is still elevated.”

Here are some more details on why the hurdle for job growth to slow by the required amount appears high on a historical basis..

The chart below shows the nine instances since 1960 that payrolls growth has slowed by more than 0.20% — roughly the amount Goldman thinks is required to restore balance to the labor market today, expressed as the change in the six-month average monthly percent change (in Goldman’s framework, monthly payroll growth needs to decline from 0.34% over the last six months to 0.11% over the next six months).

Although slowdowns of 0.20% or more have been quite uncommon outside of recessions, today’s economic backdrop – at least until a recession is officially declared in a few months – is somewhat comparable to the three historical instances where job growth slowed and a recession was avoided: ahead of the slowdowns in 1976 and 2021, job growth was running well above trend as the economy was recovering from a recession, and ahead of the slowdown in 1967, the Federal Reserve tightened monetary policy to combat inflationary pressures.

As an aside, Goldman economists points out that the recent pace of payroll growth is one of the best predictors of upcoming payrolls growth and even more useful than knowing the future rate of output growth (the predictive power of job momentum likely reflects lags in the hiring and firing process, the cost of large personnel changes, and the pro-cyclicality of capacity utilization.)

With payrolls growing just over 400k per month over the last three months (if slowing), putting a high weight on momentum would suggest a high hurdle for job growth to slow enough in coming quarters to restore balance to the labor market. However, it is also the case that employment growth has recently slowed to roughly 225k per month over the last three months in the noisier household survey, suggesting that the underlying trend could be overstated by just looking at nonfarm payrolls. Furthermore, while not captured yet by the US labor bureau, leading labor market indicators such as mass layoff announcement has surged in recent weeks, with dozens of announcements in the otherwise rock-solid tech sector. Expect similar weakness across the rest of the rest of the labor market.

Goldman itself admits as much: “recent anecdotes of hiring freezes and more selective hiring indicate that companies expect payroll growth to slow, and the most recent business activity surveys corroborate these signals.”

In the next chart, the bank constructs an aggregate index of employment growth expectations by replicating its own survey tracker methodology on the employment expectations components of eight regional Fed manufacturing and services surveys. It found that in May, this series recorded its third largest monthly decline since 2000—behind only October 2008 and March 2020—yet even so it remains at a historically elevated level… but not for long.

Which brings us to punchline #1: to get a sense of how much employment growth could slow – or rather should slow – over the coming months, Goldman estimates a model of future payroll growth based on lagged payroll growth, changes in output growth, and lagged changes in survey-based employment growth expectations. It then uses the model coefficients to project future payrolls growth based on different assumptions about the recent employment growth trend and future output growth.

Goldman derives two conclusions from the scenarios above:

- First, different plausible assumptions for the recent employment growth trend imply a wide range of outcomes for future payrolls growth: coupling the bank’s baseline (and recently cut) H2 2002 GDP growth forecast with the different employment growth trends suggests that monthly payrolls growth could range from roughly 125k up to 325k (middle column).

- Second, the balance of risks to near-term employment growth appears skewed to the upside relative to Goldman’s own forecasts of 215k per month over the next three months and 160k over the next six months (suggesting that Goldman is once again overly optimistic on the economy and will soon be slashing its jobs, and GDP, forecasts again).

One final point: while Goldman does not say it, but is generously implied in its analysis, the bigger the recession, the faster US job growth turns negative and the quicker wage growth implodes, the better for the bulls even if it sends the odds of more summer violence (if not before the midterms, then certainly next year after the GOP has won control of Congress) through the roof.