Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

This article is about why interest rates and bond yields are rising and why they will continue to rise, threatening to undermine the entire western banking system.

Rising bond yields are deferring the prospect of a central bank pivot away from fighting inflation to tackling a widely expected recession. Anyway, these expectations wrongly assume that price inflation will fall in a recession, leading to lower interest rates.

History tells us that monetary debasement, rising prices and a slump in business activity go together. Indeed, a slump in economic activity is almost certain, but interest rates will continue to rise reflecting declining purchasing powers for fiat currencies. There is nothing the monetary authorities can do to prevent it, and consequently a cyclical banking crisis, this time including both central and commercial banking systems, is bound to result.

In this article, I point out the consequences of not understanding the true role of interest rates, the fallacies surrounding commodity price formation, and why a general glut cannot happen, which according to the Keynesians drives recessions.

Blaming inflation on Russia or other external forces cuts no ice. Our crisis is entirely of our own making. Rising interest rates are our silent killer.

Introduction

Central banks were happy to suppress interest rates, even into negative territory, so long as the heavily managed consumer price inflation statistic was rising at an annualised rate of two per cent or so. But the expansion of credit during the covid pandemic changed that, with prices subsequently leaping above the two per cent target. The new price trend first became evident in mid-2020 in both producer and consumer prices. And when NATO decided to respond to the Russian invasion of Ukraine a year ago by cutting off this major energy and commodity supplier from global markets, prices soared, and interest rate suppression policies backfired.

The last time the Fed tried to let interest rates “normalise” and quantitative tightening replaced easing was before the covid pandemic. It raised its funds rate to the then dizzy heights of 2.25%–2.5% in mid-2019, leading to a repo crisis that September, and a stock market crash when the S&P 500 Index lost one-third in just five weeks between February and mid-March. QE then returned with a vengeance and the Fed funds rate was pinned to the zero bound for fully two years. And now it stands at 4.25%—5%, double the level which led to the 2020 market crisis, which was in more benign conditions.

The only thing that stands in the way of a new market crash is hope; hope that the inflation dragon is little more than a magical puff of the imagination. Initially, we were told inflation is transient. Then we were told and are still being told that it would definitely return to the 2% target, only it will take a little longer…

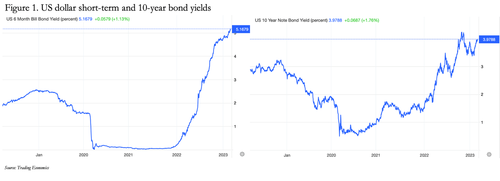

It is a story of which the market is now getting tired. After consolidating earlier rises in late-2022, bond yields are rising again, signalling that international investors and speculators are losing the faith. Figure 1 below illustrates the position for dollar bonds.

The generous gap between higher short and lower long-term yields is a measure of investors’ hope that in time interest rates will decline with the rate of inflation. A negative yield curve (positive being the normal condition) is said to foreshadow a forthcoming recession. In Keynesian terms, it indicates that the prospect of a general glut of product arriving on the market and insufficient consumer demand will lead to a decline in prices. It is an argument based on unsound reasoning more than evidential fact, but so long as investors imagine it, they continue to maintain their overall bullishness. For them, normality is consumer price inflation returning to a normal 2%, interest rates falling back towards the zero bound and credit expanding again.

An underlying assumption is that all changes in prices emanate from the supply and demand for goods, and that the purchasing power of the currency is a constant. But when the quantity of a fiat currency and associated credit expands massively and given the vagaries of human evaluation, this cannot be true.

In a ring-fenced economy, where domestic investors are the only players, the Keynesian fairy tale can persist for longer than any objective analysis suggests is reasonable. But major economies are interconnected in multiple ways, and foreign perceptions can and do differ from the domestic. At some point, the foreigners’ patience in a currency with suppressed interest rates and falling purchasing power becomes lost and the currency is sold down, unless the monetary authorities wise up to their errors and raise interest rates sufficiently to protect the currency. And when all major central banks try to protect their currencies from foreign selling by following similar inflationary policies, foreigners tend to do two things. They reduce their exposure to foreign currencies by buying back their own so that they are not exposed to foreign exchange risk, and they buy other things which they may need in future, stockpiling gold and commodities simply to get out of depreciating currencies.

There is no doubt that the currency to which foreigners are most exposed is the dollar. When they turn sellers, it is usually an unpleasant surprise for domestic investors, who have learned to live with statist mismanagement. For foreigners, the wake-up call is most likely to emanate from yet higher interest rates, being signalled by an emerging higher yield trend on the 10-year US Treasury note.

This article examines the factors which set interest rates, as well as the errors driving central bank monetary policies. It then follows up with a brief analysis of the parlous condition of banking systems, and the consequences of their failure.

The truth about interest rate mismanagement

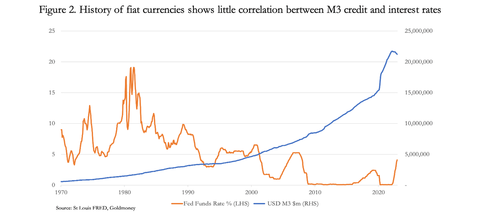

According to official monetary policy, interest rates regulate the demand for credit. But M3, which is the widest measure of currency and bank credit appears to show little or no correlation with swings in interest rates over the entire history of the purely fiat dollar (i.e., following the suspension of Bretton Woods). There might appear to be some correlation following the suppression of rates to the zero bound in early-2020. But an examination of events shows that the increase in M3 was the consequence of accelerated quantitative easing and bank deposits enlarged in a helicopter drop into individuals’ bank accounts. It had little to do with interest rates.

In recent months, the rise in the Fed funds rate has accompanied a contraction in M3, but to a large extent this contraction represents a withdrawal of credit from financial activities, which is not a policy objective. Undoubtedly, banks have become aware of increased lending risk, an awareness which is examined later in this article. But some of the deposits which would otherwise make up the M3 total have been diverted into reverse repos at the Fed by banks lacking balance sheet capacity to take them in, reducing the M3 total from what it would otherwise be by some $2 trillion.

The evidence from Figure 2 raises other important questions. Should policy planners stick with managing interest rates as the primary method of inflation control by pricing credit? Why is it that interest rates do not correlate with the quantity of money and credit: does that mean that interest rates do not represent the price of credit? Does this lack of correlation portend a policy failure?

Resolving these questions is now an urgent priority. Price inflation everywhere has erupted suddenly at a time when economies in all the major jurisdictions, according to the mainstream, appear likely to need further stimulus. The probable policy outcome will be to continue to raise interest rates, however reluctantly, while remaining free to expand the quantities of currency and credit to support economic activity, government spending, and to resolve systemic failures. In effect, that there is a link between interest rates and total credit is about to be denied by the monetary establishment itself in the pursuit of a solution.

We have moved on from the Volcker years when the inflation remedy was to raise interest rates to levels which fully discounted inflation expectations. Today the overall debt situation, which has become hyper-sensitive to interest rate rises, is more serious than it has ever been. The solution whereby central banks can print their way out of interest rate increases without collapsing their currencies appears to be a short-term illusion when the role of interest rates is properly understood. To understand why, we must answer the question posed in Figure 2 above about the non-correlation between interest rates and the quantities of currency and credit. Only then can we truly appreciate the extent of the fallacies driving contemporary monetary policies and the likely consequences.

Interest rates reflect time preference and monetary depreciation

If there is one reason why the state always fails in its monetary policies, it is the inability of the bureaucratic mind to incorporate time into decision-making. In the productive market economy, which is little more than a name for the collective actions of transacting individuals and their businesses, time is probably the most important factor. A producer incorporates time in his profit calculations, as does a consumer in his needs and desires, whether wanting something immediately or being prepared to defer his purchase. And because money is the link between both earnings and spending on one hand and savings and investment on the other, time is of the essence for money as well. It is this irrefutable fact that leads to a preference for money to be possessed sooner rather than later. And if a saver is to part with it temporarily to be returned later, naturally he or she will expect compensation for the loss of its utility.

Fundamentally, this is what interest rates in the market economy represent. It is the time preference factor, set between transacting humans, which values possession in the future less than possession today. To pure time preference, narrowly defined as the evaluation of the loss of possession, we can add an element for counterparty risk. And when transacting humans anticipate a fall in purchasing power before money owed is returned, that is yet another factor which in fiat currencies can become the most important variable.

The common central bank target for price inflation of 2% implies that interest compensation to include an element of time preference, counterparty risk, and monetary depreciation suggests a base case of perhaps 3%–4% deposit interest would be required to encourage savings to remain in a bank account. Taxation of interest income would add to this level.

US consumer prices are currently rising at 6.2% officially, the rate having been somewhat higher. But that 6.2% rate is an assumption because we can only talk of the general level of prices in the abstract. It cannot be calculated, only assessed, leaving room for statistical meddling. We can only guess at the true rate of currency depreciation and what the level of interest rates should therefore be. And we can be certain that the central bank’s opinion is biased by both political objectives and analysis biased by statist theories of money.

For now, bond markets assume that the Fed has complete control over policy outcomes. And that a yield of less than 4% for the 10-year Treasury note is fair. But if price inflation remains persistently high, then there is going to be a bond-market led crash as their bond yields gravitate towards a level determined by the sum of time preference, currency depreciation, and escalating counterparty risk. And we should note that foreigners to the US hold some $12 trillion of portfolio investments in addition to $6.4 trillion Treasury bonds, $1.3 trillion Agency bonds, $4 trillion in corporate bonds, in all $23.6 trillion, to which must be added bank deposits, commercial and Treasury bills totalling a further $7.1 trillion.[ii]

Over $30 trillion is not a trivial amount for foreigners facing rising dollar interest rates. Not only are they not obtaining satisfactory interest compensation on their dollars, but so long as they retain them, they will find that they are increasingly enmeshed in the dollar’s problems.

The situation in other financialised fiat-driven economies gives no comfort either. Despite the declining purchasing power of the Japanese yen reflected in a CPI currently rising at 4.2% annually, the Bank of Japan still insists on negative interest rates. At minus 0.19%, one-month rates have been in negative territory for the last seven years. The BoJ is struggling to keep the yield on 10-year Japanese government bonds capped at 0.5%. With consumer price inflation at current levels, I calculate that the 10-year JGB should be priced more than 30% below current levels. Mark to market valuations at this level would leave the entire Japanese banking system bankrupt and leave the Japanese government facing an impossible interest bill. The entire Japanese banking system, its currency, and economy would be lucky to survive in its current form.

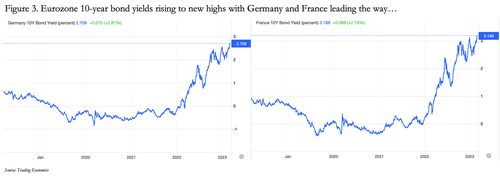

Eurozone yields are on the rise as well, with important bond yields rising to new highs. This is illustrated in Figure 3.

Part of the problem is that despite growing signs of a recession in western economies, China is awakening from extended covid lockdowns and a domestic property crisis with credit growth returning. As the sun sets in the west, it is rising in the east. China’s energy and commodity requirements will grow significantly in the coming years, which is why she has secured long-term gas and oil supply agreements with Qatar and Saudi Arabia respectively.

Analysts are becoming aware of the Chinese factor, leading to expectations that price inflation in the west will persist for longer. But they still point to a recession in Europe and America as leading to reduced consumer demand and a glut of unsold goods. We now need to explode this myth, that a recession occurs when consumers reduce their spending, leading to a general glut of products and therefore declining consumer prices.

The glut fallacy

The confusion over whether a glut can arise increases when a recession, or a slump in an economy develops. Macroeconomists expect prices to fall due to a slump in demand: in other words, they anticipate a general surplus of production remaining unsold.

There might be a negative price effect from inventory liquidation, but that is only a short-term effect. And today, with just-in-time inventory practices, the price effects from inventory liquidation are short-lived and relatively minor.

The error in Keynes’s general glut proposition comes from his denial of Say’s law, or the law of the markets, which tells us that consumers earn salaries and make profits from their labour producing goods and services. Should they find themselves unemployed, the loss of earnings will also reflect a loss of production. Both tend to decline in tandem. While production still funds consumption and a balance between them is maintained, the Keynesian view that a recession leads to a general glut – as opposed to a temporary glut in some products – is untenable.

Because the onset of a recession is expected to lead to commodity surpluses on the market, a fall in the value of commodities might appear to lead to price declines even if Say’s law is admitted. Oil and gas prices are particularly volatile in this respect, despite extraction volumes being relatively insensitive to changes in demand. And miners of precious and base metals often respond initially to commodity price weakness by increasing extraction to compensate, which can lead to further price declines. However, relationships between commodity prices and recessions are not that straightforward.

Figure 4 shows the price of WTI oil in US dollars and officially designated recessions. It should be borne in mind that evidence of a downturn in economic activity is telegraphed well ahead of the event (as is the case today) and theoretically markets will factor in a recession even before then. According to macroeconomic dogmas, allowing for these factors oil prices should fall ahead of an officially designated recession and pick up when a recession begins to end.

That being the case, the price increase from $16 in 1979 to $40 in 1980 should not have occurred. And the price increase from $18 to $35 in 1990 is similarly against the grain. But most spectacular was the move from $58 in 2007 to $140 in June 2008 in the middle of an officially designated recession.

There are examples the other way, and wars and financial crises also distort the relationship. But a clear correlation between the two does not exist. And where a correlation might be claimed, the price effects of recessions on oil and other commodities were probably exaggerated by speculative activity in derivatives, which even drove WTI prices briefly into negative territory in April 2020.

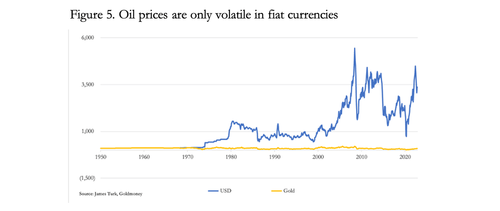

Widely ignored by market analysts and economists alike are price changes emanating from changes in a fiat currency’s valuation. The situation today is of unanchored, unsound credit. And given the sheer volatility of prices measured in fiat currencies, price changes appear to emanate from the currencies to a far greater extent than the commodities themselves. This is the only conclusion that can be drawn from our next chart in Figure 5, which is of oil priced in both fiat dollars and gold, the latter being the ultimate legal money in both Roman law and its modern successors for the last 1,800 years.

The value of gold itself has not been immune to influences emanating from fiat currencies and financial speculation in derivatives, imparting volatility into gold prices which would not otherwise exist. Nevertheless, priced in legal money oil prices have been remarkably stable.

Therefore, while we can postulate that variations in commodity prices through booms and busts may or might not give the appearance of individual commodity shortages and gluts, the clear evidence is that the price volatility seen in commodity values is in fiat currencies themselves to a far greater extent than in commodity values. And therefore, when these distortions are allowed for, they are not evidence of a commodity glut. Furthermore, empirical evidence of wholesale prices from the booms and slumps during the nineteenth century under gold coin standards confirms our analysis.

The difference between energy and commodity prices valued in a fiat currency as opposed to gold is not due to a supposed recession-induced glut, but due to changes in the availability of credit. This is what many contemporary economists, most notably followers of Keynes, failed to understand in their desire to dismiss free markets.

The banking situation

The majority by far of a circulating medium is commercial bank credit. Central bank credit in public circulation consisting entirely of bank notes usually accounts for less than ten per cent of broad money M3 or M2, the balance being bank deposit liabilities. Even though central banks pretend that their bank notes are money, this is untrue because they are a liability of a central bank and therefore counterparty credit.

In the case of the US dollar, bank notes in circulation represent 10.8% of M3. But various estimates put the true number at roughly half that, when dollar bank notes circulating abroad and those lost are considered. Therefore, 95% of dollar denominated circulating medium in the US economy is bank credit, and the lending behaviour of the commercial banking cohort is the most important determinant of economic activity.

In the initial stages of a period of rising interest rates, business is good for banks with margins for credit tending to improve. We have seen this recently, with bank profits and their share prices having risen significantly in 2022. But this is a temporary phase, inevitably followed by concern on the effects of yet higher interest rates on economic calculation. Businesses which factored lower interest rates into their calculations find that their plans begin to go awry. Bankers are aware of this problem through their own monitoring of business conditions.

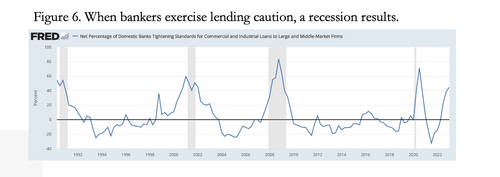

Previously, they will have expanded their balance sheets in favourable lending conditions, so that the ratio of balance sheet assets to the bank’s liability to its shareholders is bound to be higher than normal. And while in good times this enhances returns to shareholders, in bad times it rapidly destroys shareholder value. It is high balance sheet leverage which makes bankers hypersensitive to changing lending conditions. By way of confirmation, Figure 6 below shows the relationship between lending intentions and periods of recession for the US banking system.

Clearly, every recession has been preceded by a tightening of loan standards, indicating that it is the restriction, or contraction of bank credit which leads to recessions every time. The reason is that the GDP measure of growth and recession reflect changes in the level of total transactions in the economy, so it is always a measure of credit deployed, and not as is generally supposed, economic progress or regression.

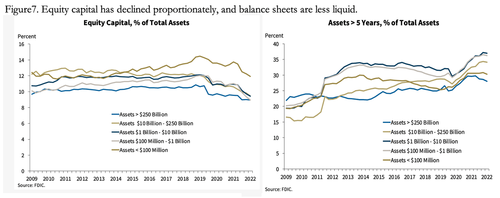

At this stage of the credit cycle, caution in bank lending becomes driven by fear of non-performing loans, the damage of which can rapidly eliminate shareholders’ funds for a highly leveraged bank balance sheet. The charts in Figure 7 further justify bankers’ caution with respect to lending policies.

The ratios above are derived from The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and are updated to last September (the next release is due later this month). In the first graph, we see that the ratio of equity capital to assets for all bank categories shows increased leverage from the last banking crisis when Lehman failed. The most highly leveraged group is the largest banks, additionally exposed to falling financial asset values.

It is this leverage ratio which affects returns to shareholders most. But for regulatory purposes it is the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET-1) ratio that matters. CET-1 is defined as common shares, stock surpluses from issuing common shares, retained earnings, unrealised gains and losses reported in the equity section of the balance sheet, and some other similar items. Excluded is goodwill, tax credits, and preference capital. The ratio is determined with risk-adjusted assets in accordance with the net stable funding ratio, which classifies sources of funding and their application. Other risk factors also apply.

It is therefore impossible for outsiders to assess the true banking position of individual banks from a regulatory point of view. But we can assume that if a bank is in danger of breaching regulatory capital minimums it will be forced to either raise more shareholders’ capital or liquidate loans. And it should be noted that nearly all of the large international banks in Japan and Europe have capitalisations significantly under book value, eliminating the prospect of additional shareholder funding, except in a capital reconstruction crisis such as recently seen in the case of Credit Suisse.

The second FDIC chart in Figure 7 is also disturbing, showing the increasing proportion of long-term loan commitments which signals declining liquidity. Traditionally, this concern has been expressed as evidence of lack of a bank’s solvency or borrowing short to lend long. In a banking crisis, it becomes a fundamental public concern which leads to runs on individual banks. But the increasing level of long-term loans almost certainly reflects a tendency for borrowers to lock in low interest rates when the Fed supressed them.

We can only assume that many banks will have hedged some or all of their illiquid exposure through interest rate swaps, passing the problems of increasing interest rates to other banks, insurance corporations and pension funds. To the extent that interest rate swap counterparties are other banks, exposure to rising interest rates and the consequences for long-term loan obligations remain within the banking system. For the whole banking cohort, hedged or unhedged, rising interest rates make these loans not only progressively unprofitable, but lending officers will begin to concern themselves about whether they can be rolled over on maturity at higher interest rates.

The US banking system is less leveraged than their opposites in the EU and Japan, at least so far as the global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) are concerned. The G-SIBs in those jurisdictions have asset to equity ratios commonly twenty times or more. And already, Credit Suisse, which was not so highly leveraged as its European neighbours, has had to be rescued. In short, higher interest rates leading to falling asset values and increasing non-performing loans together represent an existential threat to the survival of the global banking network.

Central banks are also in a parlous state

One of the primary functions of a modern central bank is to ensure the integrity of the commercial banks in its jurisdiction. We can see that further increases in interest rates are sure to threaten this integrity, raising the issue as to whether central banks are in a position to manage a global banking crisis.

At the outset, it should be stated that the reflex action of G20 leaders and their finance ministers to the Lehman failure was to ensure that in future failing banks would not be bailed out at taxpayers’expense. The concept behind so-called bail-ins was that bondholders and large depositors should be required to sacrifice their bonds and deposits for equity capital to recapitalise a bank as the initial method of rescue. Accordingly, all G20 member nations agreed to pass enabling legislation to permit bail-ins to replace the previous approach of bailing out a failing bank.

The net stable funding ratio calculation in Basel 3 regulations introduced at the G20’s behest reflects the greater risk from bail-ins with respect to large deposits, which in a banking crisis would rapidly leave the weaker banks, precipitating their failure. Under the NSFR calculation, large deposits are penalised as available stable funding, a move designed to reduce exposure to them. This is the likely reason US banks are turning down large deposits, which are now being accommodated by the Fed with its reverse repo facility.

There can be little doubt that the introduction of bail-in legislation in all major banking jurisdictions will make it more difficult for central banks to coordinate their actions in a global banking crisis. When there was one set of bail out procedures following the Lehman failure in the US, it was bad enough. Ireland’s entire economy had to be bailed by the EU, and Germany’s major banks had to be rescued. It is not even clear whether central banks will be in a position to agree to discard bail-in regulations in the interest of a coordinated practical approach to an international banking crisis.

Additionally, there is the issue of their own financial position. Since the Lehman failure, central banks have expanded their balance sheets as a counterpart of cash injections into bond markets in the form of QE. What the increase in interest rates has exposed is that central banks have paid the highest prices for their government paper, which has subsequently fallen in value. With the exception of the Bank of England, whose losses are underwritten by the UK Treasury, on a mark-to-market basis all major central banks are in a position of deeply negative equity.

In the case of the Bank of England and the Fed, it should be a simple if embarrassing matter of recapitalisation by recording a loan to their national governments as an asset and balancing it with an equity liability. In a crisis, that may be difficult enough for a sceptical public to accept, but the situation with the Bank of Japan and the ECB along with their national central banking network in the euro system is considerably more difficult.

The BoJ has pioneered QE since the year 2000, that is 23 years. The inflationary consequences at the consumer level have been subdued, partly through government subsidies estimated to suppress prices of up to 40% of Japan’s CPI, but mainly because of the Japanese habit of saving. When credit is saved and not spent, the inflation of credit is not fully reflected in consumer prices.

Until September 2019, when values on the BoJ’s then portfolio were at their highest, the BoJ had notional profits. But since then, yields have risen, and since January 2022, losses on the portfolio of JGBs alone total Y453 billion to date, 4,530 times the BoJ’s equity capital of Y100 million. At the moment, the BoJ is trying desperately to contain the situation by accelerating its bond purchases. Despite last month’s CPI inflation rate at 4.2%, yields on JGBs are still pinned at negative rates up to 2-year maturities, the 10-year JGB bond yield is 0.51%, and the 20-year is 1.2%. It amounts to a very heavily rigged market to save the BoJ’s skin.

The Eurosystem, comprising the ECB and the national central banks in the Eurozone, is also in negative equity, a condition shared by nearly all of the central banks involved. And to see the 10-year French, German, and Spanish bond yields breaking into new high ground (see Figure 3 above) signals that a new Eurozone banking crisis is unfolding.

Recapitalising the ECB will be extremely difficult, requiring legislation in most, if not all the national parliaments in the Eurozone. Not only will politicians be asked to recapitalise their own national central banks, but as shareholders in the ECB additional resources will need to be made available for its recapitalisation as well.

Given that Germany’s politicians will almost certainly want an adequate explanation for €1.16 billion euros owed to the Bundesbank through the TARGET2 settlement system recorded as an asset on its balance sheet of questionable value, the recapitalisation of the Bundesbank and the ECB is likely to be a prolonged and difficult process. And when there is a banking crisis, time is of the essence.

Summary and conclusion

In this article, it has been demonstrated why the errors in monetary policy shared by all the central banks responsible for the major western currencies and their banking systems have led to the point where the global credit system of central bank currency and commercial bank credit is on the verge of collapse. The timing will be set by interest rates rising again, which in the Eurozone and Japan are already leading the way. Interest rates are the silent killer.

Central banks are in this mess too deep to somehow unearth a conventional solution. They are meant to be the ultimate backstop for their banking systems in a crisis. Yet the Fed, the ECB, and the BoJ are themselves in a solvency crisis of their own making. An acute embarrassment for the Fed perhaps, but far more serious for the other two. And in the case of the ECB, we can rule out a rapid recapitalisation because of the structure of the euro system and unexplained TARGET2 imbalances.

Lulled into a false sense of security, these central banks misread the consequences of their own credit expansion, not realising the damage they were doing to the purchasing power of their currencies and ultimately themselves. Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, producer and consumer prices were beginning to rise, dismissed as a transient trend. We were told that inflation would return to the two per cent target and now we were told it will take just a little longer.

Monetary policy has the worst possible mistake for the authorities to make, and with negative interest rates still enforced by the BoJ, Japan is still catastrophically in denial. And official forecasts by bodies such as the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility, and the US’s Congressional Budget Office still persist in telling us that inflation will return to the 2% target, when the evidence strongly suggests otherwise. Market participants who are perennially bullish want to believe in these forecasts. But bond yields are rising again, particularly in Japan and the Eurozone which started from a negative interest rate baseline.

The truth of the matter is that interest rates and bond yields never rose to levels sufficient to keep foreign funds invested in bank deposits and financial assets. The combination of time preference, lending risk, and loss of purchasing power suggests that one-year dollar deposits should offer something over 6% at least, given a current CPI inflation rate of 6.2%. The gap between reality and current interest rates and bond yields is even more alarming in the Eurozone and Japan. And why UK gilts should yield less than equivalent US Treasuries is beyond vindication.

Bond markets are broken. Doubtless, central bankers are in denial because they do not want to face up to crashing bond and stock markets, for them vital for the preservation of economic confidence. Nor can they face up to the bankruptcies of overindebted businesses and zombie corporations unable to afford higher interest rates. It is the ultimate consequence of government officials with no skin in the game attempting to manage economic outcomes by manipulating credit and interest rates.

Having emerged from a prolonged period of declining interest rates, western capital markets still face a major readjustment, a process which has only started. And when it comes to commodity prices, for central bankers and bulls of financial assets there is likely to be a double disappointment. The easy one to understand is that the massive Chinese economy is emerging from lockdown with plans to increase capital investment across all Asia, which is why President Xi has been careful to secure long-term energy supplies. The second disappointment arises from a woeful lack of understanding about the relationship between production and consumption in a recession.

Recently, speculation has been about when the Fed will pivot from being an inflation hawk into preventing a recession, as if it is an either one or the other choice. Say’s law, which disproved the possibility of a general glut and was wrongly traduced by Keynes in 1936 is clear on the matter. Inflationists expecting a general glut will be disappointed.

As the crisis hits, foreigners will almost certainly seek to unwind their foreign currency and investment exposure. The most owned foreign currency is the dollar, with foreigners owning a total of $30 trillion in bonds, other financial assets, and bank deposits. The unwinding of these positions is bound to lead to a dollar crisis as well as a wider banking crisis, all set to be triggered by further increases in interest rates and bond yields.

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

This article is about why interest rates and bond yields are rising and why they will continue to rise, threatening to undermine the entire western banking system.

Rising bond yields are deferring the prospect of a central bank pivot away from fighting inflation to tackling a widely expected recession. Anyway, these expectations wrongly assume that price inflation will fall in a recession, leading to lower interest rates.

History tells us that monetary debasement, rising prices and a slump in business activity go together. Indeed, a slump in economic activity is almost certain, but interest rates will continue to rise reflecting declining purchasing powers for fiat currencies. There is nothing the monetary authorities can do to prevent it, and consequently a cyclical banking crisis, this time including both central and commercial banking systems, is bound to result.

In this article, I point out the consequences of not understanding the true role of interest rates, the fallacies surrounding commodity price formation, and why a general glut cannot happen, which according to the Keynesians drives recessions.

Blaming inflation on Russia or other external forces cuts no ice. Our crisis is entirely of our own making. Rising interest rates are our silent killer.

Introduction

Central banks were happy to suppress interest rates, even into negative territory, so long as the heavily managed consumer price inflation statistic was rising at an annualised rate of two per cent or so. But the expansion of credit during the covid pandemic changed that, with prices subsequently leaping above the two per cent target. The new price trend first became evident in mid-2020 in both producer and consumer prices. And when NATO decided to respond to the Russian invasion of Ukraine a year ago by cutting off this major energy and commodity supplier from global markets, prices soared, and interest rate suppression policies backfired.

The last time the Fed tried to let interest rates “normalise” and quantitative tightening replaced easing was before the covid pandemic. It raised its funds rate to the then dizzy heights of 2.25%–2.5% in mid-2019, leading to a repo crisis that September, and a stock market crash when the S&P 500 Index lost one-third in just five weeks between February and mid-March. QE then returned with a vengeance and the Fed funds rate was pinned to the zero bound for fully two years. And now it stands at 4.25%—5%, double the level which led to the 2020 market crisis, which was in more benign conditions.

The only thing that stands in the way of a new market crash is hope; hope that the inflation dragon is little more than a magical puff of the imagination. Initially, we were told inflation is transient. Then we were told and are still being told that it would definitely return to the 2% target, only it will take a little longer…

It is a story of which the market is now getting tired. After consolidating earlier rises in late-2022, bond yields are rising again, signalling that international investors and speculators are losing the faith. Figure 1 below illustrates the position for dollar bonds.

The generous gap between higher short and lower long-term yields is a measure of investors’ hope that in time interest rates will decline with the rate of inflation. A negative yield curve (positive being the normal condition) is said to foreshadow a forthcoming recession. In Keynesian terms, it indicates that the prospect of a general glut of product arriving on the market and insufficient consumer demand will lead to a decline in prices. It is an argument based on unsound reasoning more than evidential fact, but so long as investors imagine it, they continue to maintain their overall bullishness. For them, normality is consumer price inflation returning to a normal 2%, interest rates falling back towards the zero bound and credit expanding again.

An underlying assumption is that all changes in prices emanate from the supply and demand for goods, and that the purchasing power of the currency is a constant. But when the quantity of a fiat currency and associated credit expands massively and given the vagaries of human evaluation, this cannot be true.

In a ring-fenced economy, where domestic investors are the only players, the Keynesian fairy tale can persist for longer than any objective analysis suggests is reasonable. But major economies are interconnected in multiple ways, and foreign perceptions can and do differ from the domestic. At some point, the foreigners’ patience in a currency with suppressed interest rates and falling purchasing power becomes lost and the currency is sold down, unless the monetary authorities wise up to their errors and raise interest rates sufficiently to protect the currency. And when all major central banks try to protect their currencies from foreign selling by following similar inflationary policies, foreigners tend to do two things. They reduce their exposure to foreign currencies by buying back their own so that they are not exposed to foreign exchange risk, and they buy other things which they may need in future, stockpiling gold and commodities simply to get out of depreciating currencies.

There is no doubt that the currency to which foreigners are most exposed is the dollar. When they turn sellers, it is usually an unpleasant surprise for domestic investors, who have learned to live with statist mismanagement. For foreigners, the wake-up call is most likely to emanate from yet higher interest rates, being signalled by an emerging higher yield trend on the 10-year US Treasury note.

This article examines the factors which set interest rates, as well as the errors driving central bank monetary policies. It then follows up with a brief analysis of the parlous condition of banking systems, and the consequences of their failure.

The truth about interest rate mismanagement

According to official monetary policy, interest rates regulate the demand for credit. But M3, which is the widest measure of currency and bank credit appears to show little or no correlation with swings in interest rates over the entire history of the purely fiat dollar (i.e., following the suspension of Bretton Woods). There might appear to be some correlation following the suppression of rates to the zero bound in early-2020. But an examination of events shows that the increase in M3 was the consequence of accelerated quantitative easing and bank deposits enlarged in a helicopter drop into individuals’ bank accounts. It had little to do with interest rates.

In recent months, the rise in the Fed funds rate has accompanied a contraction in M3, but to a large extent this contraction represents a withdrawal of credit from financial activities, which is not a policy objective. Undoubtedly, banks have become aware of increased lending risk, an awareness which is examined later in this article. But some of the deposits which would otherwise make up the M3 total have been diverted into reverse repos at the Fed by banks lacking balance sheet capacity to take them in, reducing the M3 total from what it would otherwise be by some $2 trillion.

The evidence from Figure 2 raises other important questions. Should policy planners stick with managing interest rates as the primary method of inflation control by pricing credit? Why is it that interest rates do not correlate with the quantity of money and credit: does that mean that interest rates do not represent the price of credit? Does this lack of correlation portend a policy failure?

Resolving these questions is now an urgent priority. Price inflation everywhere has erupted suddenly at a time when economies in all the major jurisdictions, according to the mainstream, appear likely to need further stimulus. The probable policy outcome will be to continue to raise interest rates, however reluctantly, while remaining free to expand the quantities of currency and credit to support economic activity, government spending, and to resolve systemic failures. In effect, that there is a link between interest rates and total credit is about to be denied by the monetary establishment itself in the pursuit of a solution.

We have moved on from the Volcker years when the inflation remedy was to raise interest rates to levels which fully discounted inflation expectations. Today the overall debt situation, which has become hyper-sensitive to interest rate rises, is more serious than it has ever been. The solution whereby central banks can print their way out of interest rate increases without collapsing their currencies appears to be a short-term illusion when the role of interest rates is properly understood. To understand why, we must answer the question posed in Figure 2 above about the non-correlation between interest rates and the quantities of currency and credit. Only then can we truly appreciate the extent of the fallacies driving contemporary monetary policies and the likely consequences.

Interest rates reflect time preference and monetary depreciation

If there is one reason why the state always fails in its monetary policies, it is the inability of the bureaucratic mind to incorporate time into decision-making. In the productive market economy, which is little more than a name for the collective actions of transacting individuals and their businesses, time is probably the most important factor. A producer incorporates time in his profit calculations, as does a consumer in his needs and desires, whether wanting something immediately or being prepared to defer his purchase. And because money is the link between both earnings and spending on one hand and savings and investment on the other, time is of the essence for money as well. It is this irrefutable fact that leads to a preference for money to be possessed sooner rather than later. And if a saver is to part with it temporarily to be returned later, naturally he or she will expect compensation for the loss of its utility.

Fundamentally, this is what interest rates in the market economy represent. It is the time preference factor, set between transacting humans, which values possession in the future less than possession today. To pure time preference, narrowly defined as the evaluation of the loss of possession, we can add an element for counterparty risk. And when transacting humans anticipate a fall in purchasing power before money owed is returned, that is yet another factor which in fiat currencies can become the most important variable.

The common central bank target for price inflation of 2% implies that interest compensation to include an element of time preference, counterparty risk, and monetary depreciation suggests a base case of perhaps 3%–4% deposit interest would be required to encourage savings to remain in a bank account. Taxation of interest income would add to this level.

US consumer prices are currently rising at 6.2% officially, the rate having been somewhat higher. But that 6.2% rate is an assumption because we can only talk of the general level of prices in the abstract. It cannot be calculated, only assessed, leaving room for statistical meddling. We can only guess at the true rate of currency depreciation and what the level of interest rates should therefore be. And we can be certain that the central bank’s opinion is biased by both political objectives and analysis biased by statist theories of money.

For now, bond markets assume that the Fed has complete control over policy outcomes. And that a yield of less than 4% for the 10-year Treasury note is fair. But if price inflation remains persistently high, then there is going to be a bond-market led crash as their bond yields gravitate towards a level determined by the sum of time preference, currency depreciation, and escalating counterparty risk. And we should note that foreigners to the US hold some $12 trillion of portfolio investments in addition to $6.4 trillion Treasury bonds, $1.3 trillion Agency bonds, $4 trillion in corporate bonds, in all $23.6 trillion, to which must be added bank deposits, commercial and Treasury bills totalling a further $7.1 trillion.[ii]

Over $30 trillion is not a trivial amount for foreigners facing rising dollar interest rates. Not only are they not obtaining satisfactory interest compensation on their dollars, but so long as they retain them, they will find that they are increasingly enmeshed in the dollar’s problems.

The situation in other financialised fiat-driven economies gives no comfort either. Despite the declining purchasing power of the Japanese yen reflected in a CPI currently rising at 4.2% annually, the Bank of Japan still insists on negative interest rates. At minus 0.19%, one-month rates have been in negative territory for the last seven years. The BoJ is struggling to keep the yield on 10-year Japanese government bonds capped at 0.5%. With consumer price inflation at current levels, I calculate that the 10-year JGB should be priced more than 30% below current levels. Mark to market valuations at this level would leave the entire Japanese banking system bankrupt and leave the Japanese government facing an impossible interest bill. The entire Japanese banking system, its currency, and economy would be lucky to survive in its current form.

Eurozone yields are on the rise as well, with important bond yields rising to new highs. This is illustrated in Figure 3.

Part of the problem is that despite growing signs of a recession in western economies, China is awakening from extended covid lockdowns and a domestic property crisis with credit growth returning. As the sun sets in the west, it is rising in the east. China’s energy and commodity requirements will grow significantly in the coming years, which is why she has secured long-term gas and oil supply agreements with Qatar and Saudi Arabia respectively.

Analysts are becoming aware of the Chinese factor, leading to expectations that price inflation in the west will persist for longer. But they still point to a recession in Europe and America as leading to reduced consumer demand and a glut of unsold goods. We now need to explode this myth, that a recession occurs when consumers reduce their spending, leading to a general glut of products and therefore declining consumer prices.

The glut fallacy

The confusion over whether a glut can arise increases when a recession, or a slump in an economy develops. Macroeconomists expect prices to fall due to a slump in demand: in other words, they anticipate a general surplus of production remaining unsold.

There might be a negative price effect from inventory liquidation, but that is only a short-term effect. And today, with just-in-time inventory practices, the price effects from inventory liquidation are short-lived and relatively minor.

The error in Keynes’s general glut proposition comes from his denial of Say’s law, or the law of the markets, which tells us that consumers earn salaries and make profits from their labour producing goods and services. Should they find themselves unemployed, the loss of earnings will also reflect a loss of production. Both tend to decline in tandem. While production still funds consumption and a balance between them is maintained, the Keynesian view that a recession leads to a general glut – as opposed to a temporary glut in some products – is untenable.

Because the onset of a recession is expected to lead to commodity surpluses on the market, a fall in the value of commodities might appear to lead to price declines even if Say’s law is admitted. Oil and gas prices are particularly volatile in this respect, despite extraction volumes being relatively insensitive to changes in demand. And miners of precious and base metals often respond initially to commodity price weakness by increasing extraction to compensate, which can lead to further price declines. However, relationships between commodity prices and recessions are not that straightforward.

Figure 4 shows the price of WTI oil in US dollars and officially designated recessions. It should be borne in mind that evidence of a downturn in economic activity is telegraphed well ahead of the event (as is the case today) and theoretically markets will factor in a recession even before then. According to macroeconomic dogmas, allowing for these factors oil prices should fall ahead of an officially designated recession and pick up when a recession begins to end.

That being the case, the price increase from $16 in 1979 to $40 in 1980 should not have occurred. And the price increase from $18 to $35 in 1990 is similarly against the grain. But most spectacular was the move from $58 in 2007 to $140 in June 2008 in the middle of an officially designated recession.

There are examples the other way, and wars and financial crises also distort the relationship. But a clear correlation between the two does not exist. And where a correlation might be claimed, the price effects of recessions on oil and other commodities were probably exaggerated by speculative activity in derivatives, which even drove WTI prices briefly into negative territory in April 2020.

Widely ignored by market analysts and economists alike are price changes emanating from changes in a fiat currency’s valuation. The situation today is of unanchored, unsound credit. And given the sheer volatility of prices measured in fiat currencies, price changes appear to emanate from the currencies to a far greater extent than the commodities themselves. This is the only conclusion that can be drawn from our next chart in Figure 5, which is of oil priced in both fiat dollars and gold, the latter being the ultimate legal money in both Roman law and its modern successors for the last 1,800 years.

The value of gold itself has not been immune to influences emanating from fiat currencies and financial speculation in derivatives, imparting volatility into gold prices which would not otherwise exist. Nevertheless, priced in legal money oil prices have been remarkably stable.

Therefore, while we can postulate that variations in commodity prices through booms and busts may or might not give the appearance of individual commodity shortages and gluts, the clear evidence is that the price volatility seen in commodity values is in fiat currencies themselves to a far greater extent than in commodity values. And therefore, when these distortions are allowed for, they are not evidence of a commodity glut. Furthermore, empirical evidence of wholesale prices from the booms and slumps during the nineteenth century under gold coin standards confirms our analysis.

The difference between energy and commodity prices valued in a fiat currency as opposed to gold is not due to a supposed recession-induced glut, but due to changes in the availability of credit. This is what many contemporary economists, most notably followers of Keynes, failed to understand in their desire to dismiss free markets.

The banking situation

The majority by far of a circulating medium is commercial bank credit. Central bank credit in public circulation consisting entirely of bank notes usually accounts for less than ten per cent of broad money M3 or M2, the balance being bank deposit liabilities. Even though central banks pretend that their bank notes are money, this is untrue because they are a liability of a central bank and therefore counterparty credit.

In the case of the US dollar, bank notes in circulation represent 10.8% of M3. But various estimates put the true number at roughly half that, when dollar bank notes circulating abroad and those lost are considered. Therefore, 95% of dollar denominated circulating medium in the US economy is bank credit, and the lending behaviour of the commercial banking cohort is the most important determinant of economic activity.

In the initial stages of a period of rising interest rates, business is good for banks with margins for credit tending to improve. We have seen this recently, with bank profits and their share prices having risen significantly in 2022. But this is a temporary phase, inevitably followed by concern on the effects of yet higher interest rates on economic calculation. Businesses which factored lower interest rates into their calculations find that their plans begin to go awry. Bankers are aware of this problem through their own monitoring of business conditions.

Previously, they will have expanded their balance sheets in favourable lending conditions, so that the ratio of balance sheet assets to the bank’s liability to its shareholders is bound to be higher than normal. And while in good times this enhances returns to shareholders, in bad times it rapidly destroys shareholder value. It is high balance sheet leverage which makes bankers hypersensitive to changing lending conditions. By way of confirmation, Figure 6 below shows the relationship between lending intentions and periods of recession for the US banking system.

Clearly, every recession has been preceded by a tightening of loan standards, indicating that it is the restriction, or contraction of bank credit which leads to recessions every time. The reason is that the GDP measure of growth and recession reflect changes in the level of total transactions in the economy, so it is always a measure of credit deployed, and not as is generally supposed, economic progress or regression.

At this stage of the credit cycle, caution in bank lending becomes driven by fear of non-performing loans, the damage of which can rapidly eliminate shareholders’ funds for a highly leveraged bank balance sheet. The charts in Figure 7 further justify bankers’ caution with respect to lending policies.

The ratios above are derived from The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and are updated to last September (the next release is due later this month). In the first graph, we see that the ratio of equity capital to assets for all bank categories shows increased leverage from the last banking crisis when Lehman failed. The most highly leveraged group is the largest banks, additionally exposed to falling financial asset values.

It is this leverage ratio which affects returns to shareholders most. But for regulatory purposes it is the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET-1) ratio that matters. CET-1 is defined as common shares, stock surpluses from issuing common shares, retained earnings, unrealised gains and losses reported in the equity section of the balance sheet, and some other similar items. Excluded is goodwill, tax credits, and preference capital. The ratio is determined with risk-adjusted assets in accordance with the net stable funding ratio, which classifies sources of funding and their application. Other risk factors also apply.

It is therefore impossible for outsiders to assess the true banking position of individual banks from a regulatory point of view. But we can assume that if a bank is in danger of breaching regulatory capital minimums it will be forced to either raise more shareholders’ capital or liquidate loans. And it should be noted that nearly all of the large international banks in Japan and Europe have capitalisations significantly under book value, eliminating the prospect of additional shareholder funding, except in a capital reconstruction crisis such as recently seen in the case of Credit Suisse.

The second FDIC chart in Figure 7 is also disturbing, showing the increasing proportion of long-term loan commitments which signals declining liquidity. Traditionally, this concern has been expressed as evidence of lack of a bank’s solvency or borrowing short to lend long. In a banking crisis, it becomes a fundamental public concern which leads to runs on individual banks. But the increasing level of long-term loans almost certainly reflects a tendency for borrowers to lock in low interest rates when the Fed supressed them.

We can only assume that many banks will have hedged some or all of their illiquid exposure through interest rate swaps, passing the problems of increasing interest rates to other banks, insurance corporations and pension funds. To the extent that interest rate swap counterparties are other banks, exposure to rising interest rates and the consequences for long-term loan obligations remain within the banking system. For the whole banking cohort, hedged or unhedged, rising interest rates make these loans not only progressively unprofitable, but lending officers will begin to concern themselves about whether they can be rolled over on maturity at higher interest rates.

The US banking system is less leveraged than their opposites in the EU and Japan, at least so far as the global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) are concerned. The G-SIBs in those jurisdictions have asset to equity ratios commonly twenty times or more. And already, Credit Suisse, which was not so highly leveraged as its European neighbours, has had to be rescued. In short, higher interest rates leading to falling asset values and increasing non-performing loans together represent an existential threat to the survival of the global banking network.

Central banks are also in a parlous state

One of the primary functions of a modern central bank is to ensure the integrity of the commercial banks in its jurisdiction. We can see that further increases in interest rates are sure to threaten this integrity, raising the issue as to whether central banks are in a position to manage a global banking crisis.

At the outset, it should be stated that the reflex action of G20 leaders and their finance ministers to the Lehman failure was to ensure that in future failing banks would not be bailed out at taxpayers’expense. The concept behind so-called bail-ins was that bondholders and large depositors should be required to sacrifice their bonds and deposits for equity capital to recapitalise a bank as the initial method of rescue. Accordingly, all G20 member nations agreed to pass enabling legislation to permit bail-ins to replace the previous approach of bailing out a failing bank.

The net stable funding ratio calculation in Basel 3 regulations introduced at the G20’s behest reflects the greater risk from bail-ins with respect to large deposits, which in a banking crisis would rapidly leave the weaker banks, precipitating their failure. Under the NSFR calculation, large deposits are penalised as available stable funding, a move designed to reduce exposure to them. This is the likely reason US banks are turning down large deposits, which are now being accommodated by the Fed with its reverse repo facility.

There can be little doubt that the introduction of bail-in legislation in all major banking jurisdictions will make it more difficult for central banks to coordinate their actions in a global banking crisis. When there was one set of bail out procedures following the Lehman failure in the US, it was bad enough. Ireland’s entire economy had to be bailed by the EU, and Germany’s major banks had to be rescued. It is not even clear whether central banks will be in a position to agree to discard bail-in regulations in the interest of a coordinated practical approach to an international banking crisis.

Additionally, there is the issue of their own financial position. Since the Lehman failure, central banks have expanded their balance sheets as a counterpart of cash injections into bond markets in the form of QE. What the increase in interest rates has exposed is that central banks have paid the highest prices for their government paper, which has subsequently fallen in value. With the exception of the Bank of England, whose losses are underwritten by the UK Treasury, on a mark-to-market basis all major central banks are in a position of deeply negative equity.

In the case of the Bank of England and the Fed, it should be a simple if embarrassing matter of recapitalisation by recording a loan to their national governments as an asset and balancing it with an equity liability. In a crisis, that may be difficult enough for a sceptical public to accept, but the situation with the Bank of Japan and the ECB along with their national central banking network in the euro system is considerably more difficult.

The BoJ has pioneered QE since the year 2000, that is 23 years. The inflationary consequences at the consumer level have been subdued, partly through government subsidies estimated to suppress prices of up to 40% of Japan’s CPI, but mainly because of the Japanese habit of saving. When credit is saved and not spent, the inflation of credit is not fully reflected in consumer prices.

Until September 2019, when values on the BoJ’s then portfolio were at their highest, the BoJ had notional profits. But since then, yields have risen, and since January 2022, losses on the portfolio of JGBs alone total Y453 billion to date, 4,530 times the BoJ’s equity capital of Y100 million. At the moment, the BoJ is trying desperately to contain the situation by accelerating its bond purchases. Despite last month’s CPI inflation rate at 4.2%, yields on JGBs are still pinned at negative rates up to 2-year maturities, the 10-year JGB bond yield is 0.51%, and the 20-year is 1.2%. It amounts to a very heavily rigged market to save the BoJ’s skin.

The Eurosystem, comprising the ECB and the national central banks in the Eurozone, is also in negative equity, a condition shared by nearly all of the central banks involved. And to see the 10-year French, German, and Spanish bond yields breaking into new high ground (see Figure 3 above) signals that a new Eurozone banking crisis is unfolding.

Recapitalising the ECB will be extremely difficult, requiring legislation in most, if not all the national parliaments in the Eurozone. Not only will politicians be asked to recapitalise their own national central banks, but as shareholders in the ECB additional resources will need to be made available for its recapitalisation as well.

Given that Germany’s politicians will almost certainly want an adequate explanation for €1.16 billion euros owed to the Bundesbank through the TARGET2 settlement system recorded as an asset on its balance sheet of questionable value, the recapitalisation of the Bundesbank and the ECB is likely to be a prolonged and difficult process. And when there is a banking crisis, time is of the essence.

Summary and conclusion

In this article, it has been demonstrated why the errors in monetary policy shared by all the central banks responsible for the major western currencies and their banking systems have led to the point where the global credit system of central bank currency and commercial bank credit is on the verge of collapse. The timing will be set by interest rates rising again, which in the Eurozone and Japan are already leading the way. Interest rates are the silent killer.

Central banks are in this mess too deep to somehow unearth a conventional solution. They are meant to be the ultimate backstop for their banking systems in a crisis. Yet the Fed, the ECB, and the BoJ are themselves in a solvency crisis of their own making. An acute embarrassment for the Fed perhaps, but far more serious for the other two. And in the case of the ECB, we can rule out a rapid recapitalisation because of the structure of the euro system and unexplained TARGET2 imbalances.

Lulled into a false sense of security, these central banks misread the consequences of their own credit expansion, not realising the damage they were doing to the purchasing power of their currencies and ultimately themselves. Even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, producer and consumer prices were beginning to rise, dismissed as a transient trend. We were told that inflation would return to the two per cent target and now we were told it will take just a little longer.

Monetary policy has the worst possible mistake for the authorities to make, and with negative interest rates still enforced by the BoJ, Japan is still catastrophically in denial. And official forecasts by bodies such as the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility, and the US’s Congressional Budget Office still persist in telling us that inflation will return to the 2% target, when the evidence strongly suggests otherwise. Market participants who are perennially bullish want to believe in these forecasts. But bond yields are rising again, particularly in Japan and the Eurozone which started from a negative interest rate baseline.

The truth of the matter is that interest rates and bond yields never rose to levels sufficient to keep foreign funds invested in bank deposits and financial assets. The combination of time preference, lending risk, and loss of purchasing power suggests that one-year dollar deposits should offer something over 6% at least, given a current CPI inflation rate of 6.2%. The gap between reality and current interest rates and bond yields is even more alarming in the Eurozone and Japan. And why UK gilts should yield less than equivalent US Treasuries is beyond vindication.

Bond markets are broken. Doubtless, central bankers are in denial because they do not want to face up to crashing bond and stock markets, for them vital for the preservation of economic confidence. Nor can they face up to the bankruptcies of overindebted businesses and zombie corporations unable to afford higher interest rates. It is the ultimate consequence of government officials with no skin in the game attempting to manage economic outcomes by manipulating credit and interest rates.

Having emerged from a prolonged period of declining interest rates, western capital markets still face a major readjustment, a process which has only started. And when it comes to commodity prices, for central bankers and bulls of financial assets there is likely to be a double disappointment. The easy one to understand is that the massive Chinese economy is emerging from lockdown with plans to increase capital investment across all Asia, which is why President Xi has been careful to secure long-term energy supplies. The second disappointment arises from a woeful lack of understanding about the relationship between production and consumption in a recession.

Recently, speculation has been about when the Fed will pivot from being an inflation hawk into preventing a recession, as if it is an either one or the other choice. Say’s law, which disproved the possibility of a general glut and was wrongly traduced by Keynes in 1936 is clear on the matter. Inflationists expecting a general glut will be disappointed.

As the crisis hits, foreigners will almost certainly seek to unwind their foreign currency and investment exposure. The most owned foreign currency is the dollar, with foreigners owning a total of $30 trillion in bonds, other financial assets, and bank deposits. The unwinding of these positions is bound to lead to a dollar crisis as well as a wider banking crisis, all set to be triggered by further increases in interest rates and bond yields.

Loading…