This year, three particularly foul-mouthed and insulting young rappers named “Lil Jeff,” “Lil Scoom,” and “Ybcdul” recorded a song together. All three had been killed before the end of the summer. For anyone who pays attention to the underground rap scene, and the internet spectator culture that follows both the music and the violent crime that it produces, it could hardly have come as a surprise.

For young gang members, music is not just a means of seeking fame and fortunes — it is war propaganda. Take Keith Farelle “Chief Keef” Cozart, who burst out of Chicago’s Parkway Garden Homes in the early 2010s with a menacing sound and a menacing story. The lyrics of his songs contained minimal humor and poeticism. Instead, fans loved their esoteric references to the gang wars that were bloodying Chicago’s streets. This represented the birth of the “drill” genre (“drill” being slang for violent retaliation). From there, the genre has produced a consumer culture whose wares include both bars and bodies: 18-year-old Joseph “Lil JoJo” Coleman released his song “3HunnaK,” threatening death against the rival “300” street gang, and was soon murdered himself. Chicago’s Durk Devontay “Lil Durk” Banks traded threats with the teenage rapper Marc “Lil Marc” Campbell until Campbell was shot to death at a bus stop. Durk was soon filmed at the same bus stop, gloating.

Millions of fans enjoyed the thunderous, bass-heavy songs of the Chief Keefs and the Lil Durks, but for many of them, the music was just a soundtrack to the violence. Young men like Ahmed “D.Rose” Sardin and Yarmel “051 Melly” Williams could achieve online infamy without releasing a song. It was their alleged murders that made them interesting.

Over time, this has evolved into something much more troubling than the mere “gangster rap” that worried parents in the 1990s, when Tupac and Biggie Smalls achieved superstardom before being gunned down. Back then, at least, there was a certain marketing savvy, even if the gangland violence and shooting were clearly real, to how these musicians portrayed themselves as violent criminals to seem cool. What’s changed now is that the killing is the main event, and the rapping is merely ancillary.

Online, fans had begun to devour media that pieced together fragments of news, lyrics, and social media posts into dark stories about gang life. Livingston “DJ Akademiks” Allen shot to viral fame with his YouTube series The War in Chiraq. “There’s pictures of his lifeless body chalked out right next to the bus stop,” Allen excitedly announced of the late Lil Marc in one video, “But I won’t put this up in this video. I’ll leave it to you internet hounds to find it.”

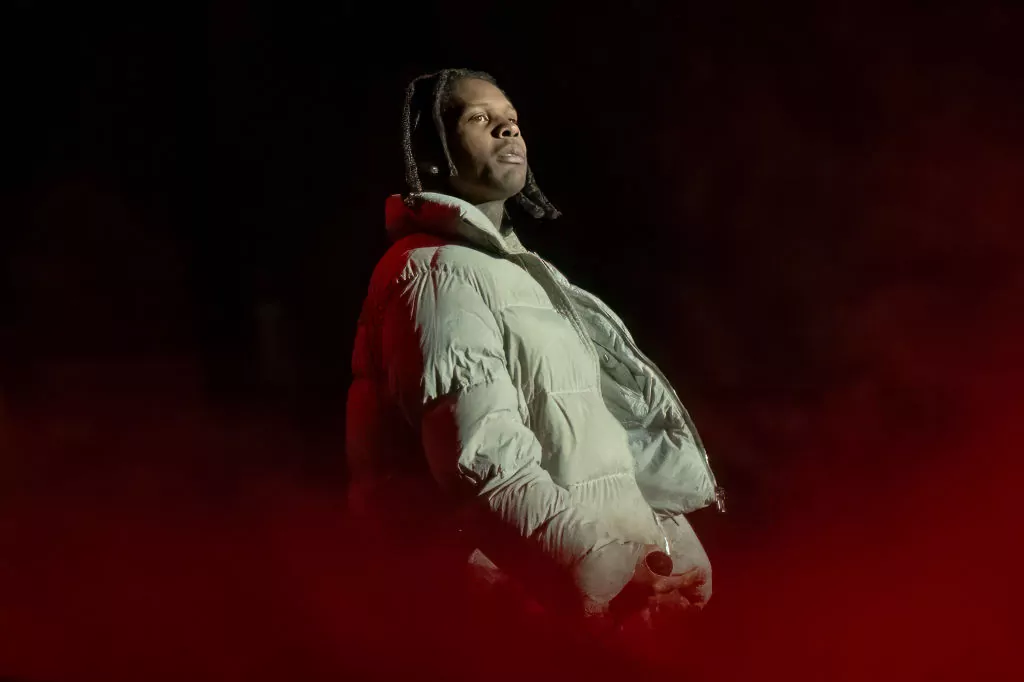

Recently, Lil Durk was arrested in October on murder-for-hire charges. Banks is among the most successful rappers in the world, with many of his songs attracting hundreds of millions of streams on Spotify. He won his first Grammy this year and was awarded multiple keys to the city in Chicago in the days before his arrest. If found guilty, Lil Durk is facing life in prison. With his massive wealth and fame, he was one of few rappers to make it off the streets, yet his lyrics, his affiliates, and his image ensured that he never quite left his old ways behind. A grand jury will decide if old habits and new fans drew him back into the darkness again.

No one attracted as much fascination as Dayvon Daquan “King Von” Bennett. Chief Keef and Lil Durk had talked about shootings that their gangs had been involved in. Von, it seemed, had been behind the gun as well as behind the microphone. His lyrics and social media posts were littered with veiled references to murders he had apparently committed. (Posthumous documentaries have speculated that Von took part in as many as seven killings.)

A cottage industry of violence voyeurs had developed. Online forums like “Chiraqology” attracted hundreds of thousands of users. Interviews and amateur documentaries drew in millions of viewers. (One of the most popular documentarians is a gangly, bespectacled British man named “Trap Lore Ross,” which makes the whole thing more surreal.) More recently, some online documentarians have even begun to film with the gang members themselves. YouTuber Brandon Buckingham was caught up in a shooting outside a recording studio last month, his cameraman hospitalized.

It would be dishonest to deny that crime is interesting — the motives and the methods and the consequences. There’s nothing inherently exploitative about producing or consuming media dedicated to its analysis. The problem is when the morbid interest obscures the human implications. Followers of American gang life can frame it as a kind of grim soap opera, with their obsessive interest in the “disses” flying back and forth, or even a sport, with their fixation on who has “got back” for who, as if perpetuating and expanding a cycle of savage violence proves anything or helps anyone.

Gang members and rappers started ramping up the sensationalism to feed this appetite for the transgressive and acquire social media notoriety (or “clout”). Songs became so morbid as to seem self-parodic. “51 Dead Opps” by the rapper “Drilla” listed dead enemies up to and including someone who had died from cancer. YouTube documentarians started busily compiling videos with titles like “Every Person Dissed In: Drilla – ‘51 DEAD OPPS.’”

In August 2020, Carlton “FBG Duck” Weekly was shot to death in the upmarket Gold Coast area of Chicago. FBG Duck had been the main enemy of King Von, with his recent track “Dead B****es” insulting several of his friends. A daylight attack in a prosperous neighborhood was reckless enough on the part of the killers, but in their pathetic thirst for infamy, they also dropped hints on social media about their involvement in the crime (one of them uploading a photo of his shoes, bearing the image of a duck being startled by a camera’s glare).

Von had little time to celebrate. He was shot and killed while pointlessly assaulting a Georgia rapper he had unrelated problems with. Soon, his Chicago friend Lil Durk was facing questions online about when he was going to get revenge. Calls to “slide” (or kill) “for Von” cluttered his comment sections. In 2022, armed men attempted to kill the rapper King Von had been feuding with, Tyquian Terrel “Quando Rondo” Bowman, and murdered his cousin, who had been traveling in the same car. Several affiliates of Lil Durk’s Only the Family collective have been arrested in the murder, and, as mentioned, Lil Durk has been arrested on the charge of hiring them for the hit.

In a 2023 interview with DJ Akademiks, Lil Durk said “for some odd reason,” he didn’t see “slide for Von” comments anymore. “Might be the water,” he smirked. This was an immensely reckless thing to say whether or not he was involved in the crime — and all to one-up strangers on the internet.

Risking not just your freedom but tremendous fame and fortune for the sake of avenging a friend who had been killed as a result of his own actions in a childish argument would be so stupid that it sounds hard to believe that anyone would actually do it. Still, rappers live and die — or feel like they will live and die — on the strength of their reputation. Of course, gang violence would be taking place with or without music and with or without social media. The Bloods and the Crips began to feud before rap music or the internet had been invented. And arguably, the police rather welcome recent musical and social media trends because it has offered them such a wealth of evidence. Still, it seems plausible that the words and deeds of impulsive young gang members are being exacerbated as they seek attention and income from the internet — and that those words and deeds are inspiring more sensational acts of vengeance.

Beyond this, there is something inherently gross about reveling in other people’s misery — about baying on the sidelines as foolish, traumatized, and misled young men take shots at one another. Perhaps as young men’s lives become more passive and alienated, being a spectator to violence and death provides a frisson of excitement lacking elsewhere.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Ben Sixsmith is online editor at the Critic.