Authored by Nathan Worcester via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

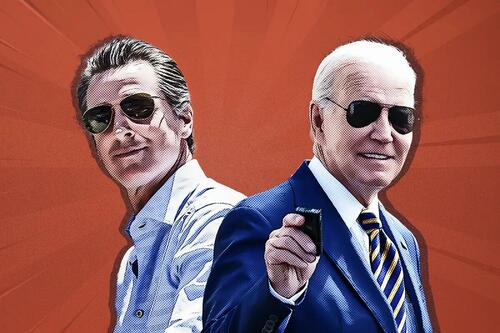

His vetoes, his foreign trips, his upcoming debate with Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis: It all adds up to something like a shadow presidential campaign by California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

It’s hard to predict how Mr. Newsom might pull it off, at least during this cycle—he has remained a steadfast supporter of incumbent President Joe Biden, and as the filing deadlines for multiple Democratic primaries have passed, he hasn’t flinched.

He could be gunning for 2028, two years after state term limits will force him out of the governor’s mansion. Or, if events line up just right, he could make his move sooner.

“I think it's been pretty obvious that Newsom has been positioning himself for a run in 2028 and to be available in 2024 should Biden's health or capacities deteriorate to the point that Democrats decide that they need another candidate,” Morris Fiorina, professor of political science and Hoover Institution fellow at Stanford University, told The Epoch Times.

California Assemblyman James Gallagher, who leads the Republicans in that chamber of the California Legislature, also cast doubt on President Biden's ability to campaign for another term.

“Right now, everybody in public is saying they’re rallying behind Joe Biden, but it’s very clear that he is deteriorating,” Mr. Gallagher told The Epoch Times.

Gloria Romero, a Democrat who was formerly majority leader of the California State Senate, said “the conundrum is the vice president," and dubbed Mr. Newsom “the replacement candidate.”

2024 as 1968

President Biden’s detractors have sometimes compared him to former President Jimmy Carter, who presided over high inflation and his own hostage crisis. But an even more war-clouded incumbent—Capitol Hill dealmaker President Lyndon B. Johnson—could offer another parallel as the United States steps up support for Israel against Hamas. Like the Vietnam War, the conflict is unpopular with much of the Democrats’ base, in part because of civilian casualties.

Amid protests over Vietnam, the unpopular President Johnson dropped out of the race early in 1968. Months of intraparty division, including the assassination of presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, culminated in the chaotic and violent Democratic convention, which was held in August in Chicago.

The party establishment’s favorite, then-Vice President Hubert Humphrey, ultimately carried off the nomination, defeating a fellow Minnesotan, the anti-war Sen. Eugene McCarthy (D-Minn.), and various others. Mr. Humphrey then fell in the general election to Richard Nixon, the man who was once counted out of national politics after he lost the 1960 presidential race to John F. Kennedy.

There are other striking similarities between 2024 and 1968. The Democratic National Convention will again take place in Chicago. Robert F. Kennedy’s son is in the running, too, albeit as an independent. And President Biden’s new Democratic primary challenger, Rep. Dean Phillips (D-Minn.), is, like Mr. Humphrey and Mr. McCarthy, a Minnesotan (though, unlike them, he isn’t running against an unpopular war).

Chuck DeVore, a former California State Assembly member now with the Texas Public Policy Foundation, told The Epoch Times that President Johnson’s departure from the field “opened up the delegates that he may have already won at that point to be able to vote as they pleased on the floor of the Democratic convention.”

“Essentially, you end up with this brokered convention. We may end up seeing something very similar in 2024,” he said.

Seeking the Center on Domestic Issues

The 2024 Chicago convention is many months away. For now, an observer can only assess what California’s governor has already done that may boost his presidential profile.

During the last legislative session, some of Mr. Newsom’s vetoes attracted media attention. For instance, he shot down legislation that would have decriminalized possession of psychedelic mushrooms. He also vetoed a bill that would have seen condoms distributed for free in California’s public high schools as well as legislation that would have altered child custody proceedings by making judges favor parents who “affirm” a minor’s transgender identity.

In a CNN opinion piece, liberal commentator Jill Filipovic called some of those vetoes “disappointing,” arguing that the governor is “a man who puts his own political future ahead of the will of the people.”

While some observers may sense a shift to the center, Ms. Romero doesn’t quite see it that way.

“It’s really political calculation,” she said. She lambasted some of the bills emanating from California’s Legislature, calling them “almost Babylon Bee-ish.” They are, in short, hard for the governor to greenlight if he wants to become competitive across a country where California values aren’t always and everywhere welcome.

She speculated that some of the vetoes show the governor trying to regain the trust of nonleftist Democrats like her, many of whom have become disillusioned with Mr. Newsom’s leadership style.

Ms. Romero described California’s leader as a chameleon-like figure who benefits from a relatively sympathetic treatment by the legacy media.

Like Ms. Romero, Mr. Gallagher characterized the vetoes as a political maneuver meant to make the governor seem less left-wing.

“The problem is, he’s still passing pretty radical policy,” Mr. Gallagher said. He cited bills such as Democratic state Sen. Scott Wiener’s S.B. 253, which will require large companies to report greenhouse gas emissions.

He said Mr. Newsom’s vetoes may allow him to look tougher on drugs while preserving his environmental agenda—a signature issue for him domestically and during his recent trip to China, where climate policy was a central concern.

Vetoes by the Numbers

Mr. DeVore suggested the vetoes may be less exceptional than they seem.

“Every governor of California, or really any governor across the country, will veto a certain number of bills that they see as just poor bills,” he said.

“I think there is a danger in reading a little too much into that,” he added, noting that the state’s past Democratic governors have also vetoed bills from the Legislature, which has skewed left for many decades.

Indeed, while some media coverage suggests Mr. Newsom’s recent vetoes take him closer to the American center, the big picture is foggier.

Mr. Newsom vetoed 156 bills and signed 890 bills during the latest legislative session. That means he shot down a little less than 15 percent of the legislation that reached him from the state’s Legislature, both chambers of which are controlled by commanding Democratic supermajorities.

That’s in keeping with what he has done before, according to an analysis by the California Senate’s Office of Research.

His vetoes, his foreign trips, his upcoming debate with Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis: It all adds up to something like a shadow presidential campaign by California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

It’s hard to predict how Mr. Newsom might pull it off, at least during this cycle—he has remained a steadfast supporter of incumbent President Joe Biden, and as the filing deadlines for multiple Democratic primaries have passed, he hasn’t flinched.

He could be gunning for 2028, two years after state term limits will force him out of the governor’s mansion. Or, if events line up just right, he could make his move sooner.

“I think it’s been pretty obvious that Newsom has been positioning himself for a run in 2028 and to be available in 2024 should Biden’s health or capacities deteriorate to the point that Democrats decide that they need another candidate,” Morris Fiorina, professor of political science and Hoover Institution fellow at Stanford University, told The Epoch Times.

California Assemblyman James Gallagher, who leads the Republicans in that chamber of the California Legislature, also cast doubt on President Biden’s ability to campaign for another term.

“Right now, everybody in public is saying they’re rallying behind Joe Biden, but it’s very clear that he is deteriorating,” Mr. Gallagher told The Epoch Times.

Gloria Romero, a Democrat who was formerly majority leader of the California State Senate, said “the conundrum is the vice president,” and dubbed Mr. Newsom “the replacement candidate.”

2024 as 1968

President Biden’s detractors have sometimes compared him to former President Jimmy Carter, who presided over high inflation and his own hostage crisis. But an even more war-clouded incumbent—Capitol Hill dealmaker President Lyndon B. Johnson—could offer another parallel as the United States steps up support for Israel against Hamas. Like the Vietnam War, the conflict is unpopular with much of the Democrats’ base, in part because of civilian casualties.

Amid protests over Vietnam, the unpopular President Johnson dropped out of the race early in 1968. Months of intraparty division, including the assassination of presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, culminated in the chaotic and violent Democratic convention, which was held in August in Chicago.

The party establishment’s favorite, then-Vice President Hubert Humphrey, ultimately carried off the nomination, defeating a fellow Minnesotan, the anti-war Sen. Eugene McCarthy (D-Minn.), and various others. Mr. Humphrey then fell in the general election to Richard Nixon, the man who was once counted out of national politics after he lost the 1960 presidential race to John F. Kennedy.

There are other striking similarities between 2024 and 1968. The Democratic National Convention will again take place in Chicago. Robert F. Kennedy’s son is in the running, too, albeit as an independent. And President Biden’s new Democratic primary challenger, Rep. Dean Phillips (D-Minn.), is, like Mr. Humphrey and Mr. McCarthy, a Minnesotan (though, unlike them, he isn’t running against an unpopular war).

Chuck DeVore, a former California State Assembly member now with the Texas Public Policy Foundation, told The Epoch Times that President Johnson’s departure from the field “opened up the delegates that he may have already won at that point to be able to vote as they pleased on the floor of the Democratic convention.”

“Essentially, you end up with this brokered convention. We may end up seeing something very similar in 2024,” he said.

Seeking the Center on Domestic Issues

The 2024 Chicago convention is many months away. For now, an observer can only assess what California’s governor has already done that may boost his presidential profile.

During the last legislative session, some of Mr. Newsom’s vetoes attracted media attention. For instance, he shot down legislation that would have decriminalized possession of psychedelic mushrooms. He also vetoed a bill that would have seen condoms distributed for free in California’s public high schools as well as legislation that would have altered child custody proceedings by making judges favor parents who “affirm” a minor’s transgender identity.

In a CNN opinion piece, liberal commentator Jill Filipovic called some of those vetoes “disappointing,” arguing that the governor is “a man who puts his own political future ahead of the will of the people.”

While some observers may sense a shift to the center, Ms. Romero doesn’t quite see it that way.

“It’s really political calculation,” she said. She lambasted some of the bills emanating from California’s Legislature, calling them “almost Babylon Bee-ish.” They are, in short, hard for the governor to greenlight if he wants to become competitive across a country where California values aren’t always and everywhere welcome.

She speculated that some of the vetoes show the governor trying to regain the trust of nonleftist Democrats like her, many of whom have become disillusioned with Mr. Newsom’s leadership style.

Ms. Romero described California’s leader as a chameleon-like figure who benefits from a relatively sympathetic treatment by the legacy media.

Like Ms. Romero, Mr. Gallagher characterized the vetoes as a political maneuver meant to make the governor seem less left-wing.

“The problem is, he’s still passing pretty radical policy,” Mr. Gallagher said. He cited bills such as Democratic state Sen. Scott Wiener’s S.B. 253, which will require large companies to report greenhouse gas emissions.

He said Mr. Newsom’s vetoes may allow him to look tougher on drugs while preserving his environmental agenda—a signature issue for him domestically and during his recent trip to China, where climate policy was a central concern.

Vetoes by the Numbers

Mr. DeVore suggested the vetoes may be less exceptional than they seem.

“Every governor of California, or really any governor across the country, will veto a certain number of bills that they see as just poor bills,” he said.

“I think there is a danger in reading a little too much into that,” he added, noting that the state’s past Democratic governors have also vetoed bills from the Legislature, which has skewed left for many decades.

Indeed, while some media coverage suggests Mr. Newsom’s recent vetoes take him closer to the American center, the big picture is foggier.

Mr. Newsom vetoed 156 bills and signed 890 bills during the latest legislative session. That means he shot down a little less than 15 percent of the legislation that reached him from the state’s Legislature, both chambers of which are controlled by commanding Democratic supermajorities.

That’s in keeping with what he has done before, according to an analysis by the California Senate’s Office of Research.