In the wake of Western sanctions on Russia after the invasion of Ukraine, many central banks are bringing their gold home for safekeeping, according to an Invesco survey of central banks and sovereign wealth funds.

Many central banks and sovereign wealth funds hold their gold reserves in overseas vaults in London and other Western nations, but there is a growing gold repatriation trend due to concerns about sanctions and security.

Eighty-five percent of the 85 sovereign wealth funds and 57 central banks surveyed indicated they think price inflation will be higher in the next decade than the last.

They also expressed concern about growing geopolitical tensions and the trajectory of the US dollar. As a result, central bankers and sovereign wealth fund managers are “fundamentally” rethinking their strategies.

Nearly 80% of the 142 institutions surveyed cited geopolitical tensions as the biggest risk over the next decade. Eighty-three percent cited inflation as a concern over the next 12 months.

“The funds and the central banks are now trying to get to grips with higher inflation,” Invesco head of official institutions Rod Ringrow who oversaw the survey said.

“It’s a big sea of change.”

Gold is perceived as a good bet in that environment.

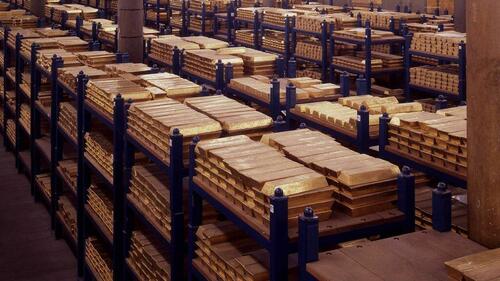

Central banks and sovereign wealth funds have always included gold in their asset mix, and over the last several years, many central banks have been adding more gold to their reserves. According to the 2023 Central Bank Gold Reserve Survey released by the World Gold Council, 24% of central banks plan to further increase gold reserves in the next 12 months. Seventy-one percent of central banks surveyed believe the overall level of global reserves will increase in the next 12 months. That was a 10-point increase over last year.

But according to the Invesco survey, a “substantial share” of central banks expressed concern about how the US and other Western countries froze almost half of Russia’s $650 billion gold and forex reserves. As a result, 68% of the banks surveyed said they are keeping their gold reserve within their country’s borders. This was up from 50% in 2020.

One central bank official, who was quoted anonymously, said, “We did have it [gold] held in London… but now we’ve transferred it back to our country to hold as a safe haven asset and to keep it safe.”

Invesco head of official institutions Rod Ringrow oversaw the survey and said the anonymous central banker reflected a widely-held view.

‘If it’s my gold then I want it in my country,’ has been the mantra we have seen in the last year or so.”

A number of countries have publicly repatriated their gold reserves over the last decade.

In 2019, Poland brought home 100 tons of gold. When he announced the move, National Bank of Poland Governor Adam Glapiński told reporters, “The gold symbolizes the strength of the country.”

Hungary and Romania also repatriated some of their gold reserves around that same time period.

In the summer of 2017, Germany completed a project to bring half of its gold reserves back inside its borders. The country moved some $31 billion worth of the yellow metal back to Germany from vaults in England, France and the US. In 2015, Australia launched efforts to bring half of its reserves home. The Netherlands and Belgium have also initiated repatriation programs.

Gold repatriation underscores the importance of holding physical gold where you can easily access it. Gold-backed exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and “paper gold” have their place. But true security and stability come from the physical possession of precious metals. If you can’t hold it in your hand, you don’t really possess it. That’s exactly why these countries are bringing their gold home — to keep it safe within their own vaults.

In the wake of Western sanctions on Russia after the invasion of Ukraine, many central banks are bringing their gold home for safekeeping, according to an Invesco survey of central banks and sovereign wealth funds.

Many central banks and sovereign wealth funds hold their gold reserves in overseas vaults in London and other Western nations, but there is a growing gold repatriation trend due to concerns about sanctions and security.

Eighty-five percent of the 85 sovereign wealth funds and 57 central banks surveyed indicated they think price inflation will be higher in the next decade than the last.

They also expressed concern about growing geopolitical tensions and the trajectory of the US dollar. As a result, central bankers and sovereign wealth fund managers are “fundamentally” rethinking their strategies.

Nearly 80% of the 142 institutions surveyed cited geopolitical tensions as the biggest risk over the next decade. Eighty-three percent cited inflation as a concern over the next 12 months.

“The funds and the central banks are now trying to get to grips with higher inflation,” Invesco head of official institutions Rod Ringrow who oversaw the survey said.

“It’s a big sea of change.”

Gold is perceived as a good bet in that environment.

Central banks and sovereign wealth funds have always included gold in their asset mix, and over the last several years, many central banks have been adding more gold to their reserves. According to the 2023 Central Bank Gold Reserve Survey released by the World Gold Council, 24% of central banks plan to further increase gold reserves in the next 12 months. Seventy-one percent of central banks surveyed believe the overall level of global reserves will increase in the next 12 months. That was a 10-point increase over last year.

But according to the Invesco survey, a “substantial share” of central banks expressed concern about how the US and other Western countries froze almost half of Russia’s $650 billion gold and forex reserves. As a result, 68% of the banks surveyed said they are keeping their gold reserve within their country’s borders. This was up from 50% in 2020.

One central bank official, who was quoted anonymously, said, “We did have it [gold] held in London… but now we’ve transferred it back to our country to hold as a safe haven asset and to keep it safe.”

Invesco head of official institutions Rod Ringrow oversaw the survey and said the anonymous central banker reflected a widely-held view.

‘If it’s my gold then I want it in my country,’ has been the mantra we have seen in the last year or so.”

A number of countries have publicly repatriated their gold reserves over the last decade.

In 2019, Poland brought home 100 tons of gold. When he announced the move, National Bank of Poland Governor Adam Glapiński told reporters, “The gold symbolizes the strength of the country.”

Hungary and Romania also repatriated some of their gold reserves around that same time period.

In the summer of 2017, Germany completed a project to bring half of its gold reserves back inside its borders. The country moved some $31 billion worth of the yellow metal back to Germany from vaults in England, France and the US. In 2015, Australia launched efforts to bring half of its reserves home. The Netherlands and Belgium have also initiated repatriation programs.

Gold repatriation underscores the importance of holding physical gold where you can easily access it. Gold-backed exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and “paper gold” have their place. But true security and stability come from the physical possession of precious metals. If you can’t hold it in your hand, you don’t really possess it. That’s exactly why these countries are bringing their gold home — to keep it safe within their own vaults.

Loading…