Authored by Mark Stricherz via RealClear Wire,

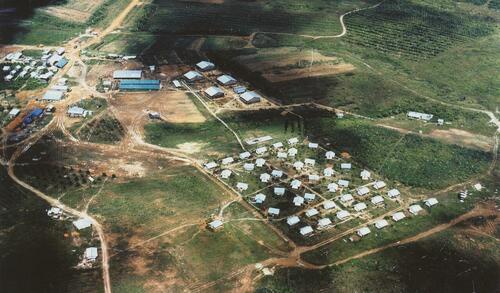

Forty-five years later, what happened in Guyana, South America, is still shocking. More than 900 members of the Peoples Temple organization, a former San Francisco-based Disciples of Christ congregation that in exile turned into a militant New Left group, died from ingesting or being injected with potassium cyanide-laced poison. Many corpses were found face down and holding hands in and around the pavilion in the farm commune known as Jonestown, an indication they died willingly.

The large number of dead and the bizarre manner of death gave rise to a famous, if technically inaccurate, warning to followers of any stripe: “Don’t drink the Kool-Aid.” The Jonestown massacre has come to be seen as a cautionary tale about the perils of blind obedience to a leader. Today, some progressives liken supporters of former President Donald Trump to the doomed Temple members.

Such warnings never felt quite right to me. Growing up in the Bay Area, I learned a different lesson about Jonestown. My cousin Valerie was a San Francisco public school teacher, and eight or nine of her former students were among those who died in Jonestown. They were not wild-eyed followers of Peoples Temple leader Jim Jones. They were murder victims.

All told, 304 American infants, toddlers, preschoolers, school-age children, and teenagers died in the massacre, a number larger than U.S. military casualties during the Persian Gulf War. Either their parents or Temple staff members forced them to drink cups of potassium cyanide-laced Flavor-Aid or injected them with the poison.

An untold number of adults, too, were murdered, according to Dr. Leslie Mootoo, a Guyanese pathologist and the first medical doctor on the scene after the massacre. Mootoo performed toxicology studies or spot checks on 64 corpses in Jonestown on Nov. 20 and Nov. 21, 1978. What he noticed was that more than 50 syringes were present and that some corpses had puncture wounds on their upper arms that appeared to have been caused by a hypodermic needle.

To be sure, many Temple members committed suicide. What their suicides confirm is that the Jonestown massacre was more complicated than the public and some historians believe.

Yes, the mass deaths, the largest in U.S. history outside of natural disasters or wartime until the September 11, 2001, attacks, are an object lesson in the perils of being an obedient follower. Yet incredible as it may sound, the Jonestown massacre had another side.

Twenty-five Americans escaped from Jonestown, and many more nearly did so. Their stories represent a hopeful tale about a political leader.

I base this conclusion on material that for decades was inaccessible to researchers: 22,000 pages of files compiled by Congress in its investigation into the assassination of Rep. Leo J. Ryan, a California Democrat, and the State Department’s inquiry into Jonestown. The documents and audio tapes, stored at the National Archives of Washington, D.C., offer an unparalleled look at the government’s oversight of Jonestown.

Congressman Ryan arrived in Jonestown on Friday, Nov. 17, 1978, to investigate charges of abuse and false imprisonment. Five years later, he would receive a posthumous Congressional Gold Medal.

“It was typical of Leo Ryan’s concern for his constituents that he would investigate personally the rumors of mistreatment in Jonestown that reportedly affected so many from his district,” President Ronald Reagan said in November 1983.

For more than a year before the massacre, Jonestown residents were, practically speaking, inmates in an open-air prison. Unless they were Jones’ trusted lieutenants or made a hair-raising escape through a tropical rainforest, they were held in bondage. When Temple teenagers Thom Bogue and Brian Davis attempted to escape in late 1977, Jones ordered his security guards to bring the boys back. The teens were tracked down, returned to the compound, and shackled in leg irons.

Jones ruled like a cruel prison warden, and he could not abide his secret being exposed. By the afternoon of Saturday, Nov. 18, 1978, Jones’ weakness was palpable. He was losing the faith of his flock. Fifteen Temple members agreed to leave with Ryan out of Jonestown, and another 11 had escaped through the jungle. “Leave us,” Jones told NBC News’ Don Harris in his final interview. “I just beg you, please leave us. We’ll bother nobody.”

Jones’ pleas were in vain. People escaped anyway, an act which required not just physical courage, but force of will. “The level of indoctrination we were under was astounding,” Vern Gosney, a former Temple member who left with Ryan, wrote in 2013. “Lack of sleep and decent food, endless meetings with Jones haranguing us, and those goddamn loudspeakers going on 24 hours a day, seven days a week, had taken their toll. My mind was a mass of confusion and conflict.”

As Ryan liberated the prisoners, 47-year-old Jones expressed despair. “I’m defeated,” he said. “I might as well die.”

Some historians attribute Jones’ despair and incompetence to a high fever and drug use. This is, at a minimum, simplistic.

Only 10 days before Ryan arrived, Consul Doug Ellice and Vice-Consul T. Dennis Reece from the American Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana, inspected Jonestown. Jones’ ailments didn’t stop him from pulling the wool over the young diplomats’ eyes. They found no evidence Americans were falsely imprisoned. “[Jonestown] reminded me of a Boy Scout camp,” Ellice told congressional investigators.

They weren’t the only U.S. government officials who failed the victims. Since the Temple’s mass exodus from California in mid-1977, State Department officials had visited Jonestown an additional four times. The diplomats were so clueless about what was happening at the compound that the embassy issued this statement: “The Consul is convinced on the basis of his personal observations and conversations with Peoples Temple members and Guyanese government officials that it is improbable that anyone is being held against their will in Jonestown … They appear adequately fed and expressed satisfaction with their lives.”

Leo Ryan’s success in exposing Jones was no accident. The son of two journalists, the 53-year-old congressman had developed a rare expertise in investigating prisons. In all, he had investigated five prisons on three continents. Among those was Tan Hiep in South Vietnam in 1974 and what he called the “national jail” that was East Berlin, Germany, in 1970.

Ryan knew his way around a prison camp, and his investigation showed as much. Not only did Ryan bring significantly more officials and inspectors to Jonestown than those from the State Department, but Ryan’s traveling party also stayed longer.

The diplomats’ inspections were much less thorough. No more than two showed up, and they stayed for four to five hours typically. When Ryan arrived on Nov. 17, 1978, he had 16 members in his traveling party, and they stayed in Guyana overnight.

Ryan’s band of journalists and Temple family members overwhelmed Jones. As one escapee, Dale Parks, reflected in 2017, “When Embassy and State officials showed up in Jonestown, Jones was in control. He showed them what he wanted them to see. Only a few officials were there, and they were easy to lead around. Ryan’s party was different. It was much larger. Jones couldn’t control them.”

The second reason Ryan is worthy of remembering is because he alone stuck his neck out for Jonestown’s residents and his constituents. A Ryan constituent, Clare Bouquet, had written the State Department, the Guyanese government, and California’s congressional delegation about her adult son Brian, who had moved to Jonestown without telling her. When Bouquet met with Ryan at his office in San Mateo, Calif., in August 1978, she noted that hardly any officials had helped her.

Why did Ryan care? Critics say Ryan had ulterior motives. Reagan administration lawyer John G. Roberts Jr., now Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, suggested the congressman was a “publicity hound.”

This was simplistic. Although he was not camera shy, Ryan’s motivations ran much deeper. For one thing, he knew firsthand the pain of an unexpected family loss. When he was 11 years old, his father was struck by a motorist and died. When he was 42, his secretary in the California Assembly, Miriam Martin, a married mother of three, was bludgeoned to death by a robber inside her family’s home in the Sacramento suburbs. When he was 51, his teenage nephew, Ramsey Devereaux, disappeared mysteriously after joining the Church of Scientology.

Even so, what Leo Ryan did on Nov. 18, 1978, was incredible.

No fewer than eight local, state, federal, and international government agencies had investigated Jim Jones since 1971. Those included the State Department, whose embassy in Guyana was less than 150 miles from Jonestown. None held Jones to account for his crimes and misdemeanors. Ryan was based more than 2,000 miles away on Capitol Hill and in the San Francisco Bay Area. Yet he held Jones to account and rescued 25 Americans, directly and indirectly, from the Temple leader’s grip.

Ryan recognized that investigating Jones could be dangerous; he considered taking a gun to protect himself from robbers. Yet neither he nor anyone else expected Jones to unleash the violence he did. In the end, Ryan, too, was a victim. At a remote dirt airstrip in Port Kaituma, Guyana, he and four others were assassinated by Jones’ hit squad while escorting 14 Americans to safety.

“Don’t drink the Kool-Aid” is a fair warning to followers. But “Are you willing to put your body on the line to fight injustice?” is a fair question to ask leaders. Imagine if those from the Catholic Church, the Boy Scouts, or major universities had responded as forcefully to complaints of abuse leveled against institutions as Rep. Leo Ryan. The ones who answer yes, like this tragic hero, deserve not only honor but also fanfare.

Mark Stricherz, a reporter and writer in Washington, D.C., is working on a book about Jonestown. He maintains a weekly blog on nonfiction writing at www.MarkStricherz.com.

Forty-five years later, what happened in Guyana, South America, is still shocking. More than 900 members of the Peoples Temple organization, a former San Francisco-based Disciples of Christ congregation that in exile turned into a militant New Left group, died from ingesting or being injected with potassium cyanide-laced poison. Many corpses were found face down and holding hands in and around the pavilion in the farm commune known as Jonestown, an indication they died willingly.

The large number of dead and the bizarre manner of death gave rise to a famous, if technically inaccurate, warning to followers of any stripe: “Don’t drink the Kool-Aid.” The Jonestown massacre has come to be seen as a cautionary tale about the perils of blind obedience to a leader. Today, some progressives liken supporters of former President Donald Trump to the doomed Temple members.

Such warnings never felt quite right to me. Growing up in the Bay Area, I learned a different lesson about Jonestown. My cousin Valerie was a San Francisco public school teacher, and eight or nine of her former students were among those who died in Jonestown. They were not wild-eyed followers of Peoples Temple leader Jim Jones. They were murder victims.

All told, 304 American infants, toddlers, preschoolers, school-age children, and teenagers died in the massacre, a number larger than U.S. military casualties during the Persian Gulf War. Either their parents or Temple staff members forced them to drink cups of potassium cyanide-laced Flavor-Aid or injected them with the poison.

An untold number of adults, too, were murdered, according to Dr. Leslie Mootoo, a Guyanese pathologist and the first medical doctor on the scene after the massacre. Mootoo performed toxicology studies or spot checks on 64 corpses in Jonestown on Nov. 20 and Nov. 21, 1978. What he noticed was that more than 50 syringes were present and that some corpses had puncture wounds on their upper arms that appeared to have been caused by a hypodermic needle.

To be sure, many Temple members committed suicide. What their suicides confirm is that the Jonestown massacre was more complicated than the public and some historians believe.

Yes, the mass deaths, the largest in U.S. history outside of natural disasters or wartime until the September 11, 2001, attacks, are an object lesson in the perils of being an obedient follower. Yet incredible as it may sound, the Jonestown massacre had another side.

Twenty-five Americans escaped from Jonestown, and many more nearly did so. Their stories represent a hopeful tale about a political leader.

I base this conclusion on material that for decades was inaccessible to researchers: 22,000 pages of files compiled by Congress in its investigation into the assassination of Rep. Leo J. Ryan, a California Democrat, and the State Department’s inquiry into Jonestown. The documents and audio tapes, stored at the National Archives of Washington, D.C., offer an unparalleled look at the government’s oversight of Jonestown.

Congressman Ryan arrived in Jonestown on Friday, Nov. 17, 1978, to investigate charges of abuse and false imprisonment. Five years later, he would receive a posthumous Congressional Gold Medal.

“It was typical of Leo Ryan’s concern for his constituents that he would investigate personally the rumors of mistreatment in Jonestown that reportedly affected so many from his district,” President Ronald Reagan said in November 1983.

For more than a year before the massacre, Jonestown residents were, practically speaking, inmates in an open-air prison. Unless they were Jones’ trusted lieutenants or made a hair-raising escape through a tropical rainforest, they were held in bondage. When Temple teenagers Thom Bogue and Brian Davis attempted to escape in late 1977, Jones ordered his security guards to bring the boys back. The teens were tracked down, returned to the compound, and shackled in leg irons.

Jones ruled like a cruel prison warden, and he could not abide his secret being exposed. By the afternoon of Saturday, Nov. 18, 1978, Jones’ weakness was palpable. He was losing the faith of his flock. Fifteen Temple members agreed to leave with Ryan out of Jonestown, and another 11 had escaped through the jungle. “Leave us,” Jones told NBC News’ Don Harris in his final interview. “I just beg you, please leave us. We’ll bother nobody.”

Jones’ pleas were in vain. People escaped anyway, an act which required not just physical courage, but force of will. “The level of indoctrination we were under was astounding,” Vern Gosney, a former Temple member who left with Ryan, wrote in 2013. “Lack of sleep and decent food, endless meetings with Jones haranguing us, and those goddamn loudspeakers going on 24 hours a day, seven days a week, had taken their toll. My mind was a mass of confusion and conflict.”

As Ryan liberated the prisoners, 47-year-old Jones expressed despair. “I’m defeated,” he said. “I might as well die.”

Some historians attribute Jones’ despair and incompetence to a high fever and drug use. This is, at a minimum, simplistic.

Only 10 days before Ryan arrived, Consul Doug Ellice and Vice-Consul T. Dennis Reece from the American Embassy in Georgetown, Guyana, inspected Jonestown. Jones’ ailments didn’t stop him from pulling the wool over the young diplomats’ eyes. They found no evidence Americans were falsely imprisoned. “[Jonestown] reminded me of a Boy Scout camp,” Ellice told congressional investigators.

They weren’t the only U.S. government officials who failed the victims. Since the Temple’s mass exodus from California in mid-1977, State Department officials had visited Jonestown an additional four times. The diplomats were so clueless about what was happening at the compound that the embassy issued this statement: “The Consul is convinced on the basis of his personal observations and conversations with Peoples Temple members and Guyanese government officials that it is improbable that anyone is being held against their will in Jonestown … They appear adequately fed and expressed satisfaction with their lives.”

Leo Ryan’s success in exposing Jones was no accident. The son of two journalists, the 53-year-old congressman had developed a rare expertise in investigating prisons. In all, he had investigated five prisons on three continents. Among those was Tan Hiep in South Vietnam in 1974 and what he called the “national jail” that was East Berlin, Germany, in 1970.

Ryan knew his way around a prison camp, and his investigation showed as much. Not only did Ryan bring significantly more officials and inspectors to Jonestown than those from the State Department, but Ryan’s traveling party also stayed longer.

The diplomats’ inspections were much less thorough. No more than two showed up, and they stayed for four to five hours typically. When Ryan arrived on Nov. 17, 1978, he had 16 members in his traveling party, and they stayed in Guyana overnight.

Ryan’s band of journalists and Temple family members overwhelmed Jones. As one escapee, Dale Parks, reflected in 2017, “When Embassy and State officials showed up in Jonestown, Jones was in control. He showed them what he wanted them to see. Only a few officials were there, and they were easy to lead around. Ryan’s party was different. It was much larger. Jones couldn’t control them.”

The second reason Ryan is worthy of remembering is because he alone stuck his neck out for Jonestown’s residents and his constituents. A Ryan constituent, Clare Bouquet, had written the State Department, the Guyanese government, and California’s congressional delegation about her adult son Brian, who had moved to Jonestown without telling her. When Bouquet met with Ryan at his office in San Mateo, Calif., in August 1978, she noted that hardly any officials had helped her.

Why did Ryan care? Critics say Ryan had ulterior motives. Reagan administration lawyer John G. Roberts Jr., now Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, suggested the congressman was a “publicity hound.”

This was simplistic. Although he was not camera shy, Ryan’s motivations ran much deeper. For one thing, he knew firsthand the pain of an unexpected family loss. When he was 11 years old, his father was struck by a motorist and died. When he was 42, his secretary in the California Assembly, Miriam Martin, a married mother of three, was bludgeoned to death by a robber inside her family’s home in the Sacramento suburbs. When he was 51, his teenage nephew, Ramsey Devereaux, disappeared mysteriously after joining the Church of Scientology.

Even so, what Leo Ryan did on Nov. 18, 1978, was incredible.

No fewer than eight local, state, federal, and international government agencies had investigated Jim Jones since 1971. Those included the State Department, whose embassy in Guyana was less than 150 miles from Jonestown. None held Jones to account for his crimes and misdemeanors. Ryan was based more than 2,000 miles away on Capitol Hill and in the San Francisco Bay Area. Yet he held Jones to account and rescued 25 Americans, directly and indirectly, from the Temple leader’s grip.

Ryan recognized that investigating Jones could be dangerous; he considered taking a gun to protect himself from robbers. Yet neither he nor anyone else expected Jones to unleash the violence he did. In the end, Ryan, too, was a victim. At a remote dirt airstrip in Port Kaituma, Guyana, he and four others were assassinated by Jones’ hit squad while escorting 14 Americans to safety.

“Don’t drink the Kool-Aid” is a fair warning to followers. But “Are you willing to put your body on the line to fight injustice?” is a fair question to ask leaders. Imagine if those from the Catholic Church, the Boy Scouts, or major universities had responded as forcefully to complaints of abuse leveled against institutions as Rep. Leo Ryan. The ones who answer yes, like this tragic hero, deserve not only honor but also fanfare.

Mark Stricherz, a reporter and writer in Washington, D.C., is working on a book about Jonestown. He maintains a weekly blog on nonfiction writing at www.MarkStricherz.com.