Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

The evidence strongly suggests that a combined interest rate, economic and currency crisis for the US and its western alliance will continue in 2023.

This article focuses on credit, its constraints, and why quantitative easing has already crowded out private sector activity. Adjusting M2 money supply for accumulating QE indicates the degree to which this has driven the US tax base into deep recession. And the wider effects on credit in the economy should not be ignored.

After a brief partial recovery from the covid crisis in US government finances, they are likely to start deteriorating again due to a deepening recession of private sector activity. Funding these deficits depends on foreign inward investment flows, which are faltering. Rising interest rates and an ongoing bear market make funding from this source hard to envisage.

Meanwhile, from his public statements President Putin is fully aware of these difficulties, and a consequence of the western alliance increasing their support and involvement in Ukraine makes it almost certain that Putin will take the opportunity to push the dollar over the edge.

Credit is much more than bank deposits

Economics is about credit, and its balance sheet twin, debt. Debt is either productive, in which case it can extinguish credit in due course, or it is not, and credit must be extended or written off. Money almost never comes into it. Money is distinguished from credit by having no counterparty risk, which credit always has. The role of money is to stabilise the purchasing power of credit. And the only legal form of money is metallic; gold, silver, or copper usually rendered into coin for enhanced fungibility.

Credit is created between consenting parties. It facilitates commerce, created to circulate existing commodities, and to transform them into consumer goods. The chain of production requires credit, from miner, grower, or importer, to manufacturer, wholesaler, retailer and customer or consumer. Credit in the production chain is only extinguished when the customer or consumer pays for the end product. Until then, the entire production chain must either have money or arrange for credit to pay for their inputs.

Providers of this credit include the widest range of economic actors in an economy as well as the banks. When we talk of the misnamed money supply as the measure of credit in an economy, we are looking at the tip of an iceberg, leading us to think that debt in the form of bank notes and deposit accounts owed to individuals and businesses is the extent of it. Changes in the banking sector’s risk appetite drive a larger change in unrecorded credit conditions. We must accept that changes in the level of officially recognised debt are merely symptomatic of larger changes in payment obligations in the economy.

The role of credit is not adequately understood by economists. Keynes’s General Theory has only one indexed reference to credit in the entire book, the vade mecum for all macroeconomists. Even the title includes “money” when it is actually all about credit. Von Mises expounds on credit to a considerable degree in his Human Action, but this is an exception. And even his followers today are often unclear about the distinction between money and credit.

Economists and commentators have begun to understand that credit is not limited to banks, by admitting to the existence of shadow banking, a loose definition for financial institutions which do not have a banking licence but circulate credit. The Bank for International Settlements which monitors shadow banking appears to suspect shadow banks of creating credit without the requirement of a banking licence. There appears to be a confusion here: the BIS’s starting point is that credit is the preserve of a licenced bank. The mistake is to not understand the wider role of non-bank credit in economic activity.

But these institutions, ranging from insurance companies and pension funds to various forms of financial intermediaries and agents, unconsciously create credit by allowing time to elapse between a commitment giving rise to an obligation, and its settlement. Even next day settlement is a debt obligation for a buyer, or credit extended by a seller. Delivery against settlement is a credit obligation for both parties in a transaction. Futures, forwards, and options are credit obligations in favour of a buyer, which can be traded. And when a broker insists a client must have a credit in his account before investing, or to deliver securities before selling, credits and obligations are also created.

Therefore, credit has the same effect as money (which is very rarely used) in every transaction, financial or non-financial. All the debts in the accounts of businesses are part of the circulating medium in an economy, including bills of exchange and other tradable obligations. And at each transfer a new credit, debt, or right of action is created, while others are extinguished.

A banking system provides a base for further credit expansion because all credit transactions are ultimately settled in bank notes, which are an obligation of the note issuer (in practice today, a central bank) or through the novation of a bank deposit, being an obligation of a commercial bank. Banks are simply dealers in credit. As such, they facilitate not just their own dealings, but all credit creation and expunction.

The reason for making the point about the true extent of credit is that it is a mistake to think that the statistical expansion, or contraction of it, conventionally measured by the misnamed money supply, is the true extent of a change in outstanding credit. Central banks in particular act as if they believe that by influencing the height of the visible tip of the credit iceberg, they can simply ignore the consequences for the rest.

It is also worth making this point so that we can assess how the economies of the western alliance will fare in the year ahead — the American-led NATO and other nations adhering to its sphere of influence. With signs of bank credit no longer expanding and, in some cases, contracting, and with price inflation continuing at destructive levels and a recession threatened, it is rarely so important to understand credit and its role in an economy.

We also need to have a true understanding of credit to assess the prospects for China’s economy, which appears to be set on a different course. Emerging from lockdown and in the light of favourable geopolitical developments while the western alliance is tipping into recession, the prospects for China’s economy are rapidly improving.

Interest rates in 2023

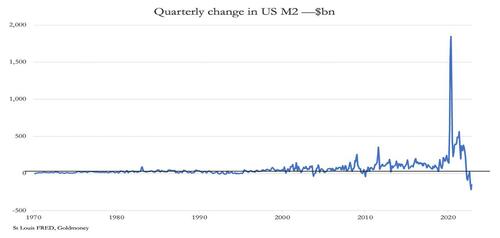

That the long-term trend of declining interest rates for the major fiat currencies over the last four decades came to an end in 2021 is now beyond question. That this trend fostered a continuing appreciation of asset values is fundamental to an understanding of the consequences. And that the expansion of bank credit supporting a widening plethora of financial credit has stopped, is now only beginning to be register. If we look at the quarterly rate of change in US M2 money supply, this is now evident.

Since the Bretton Woods agreement was abandoned in 1971, there has not been as severe a contraction of US dollar bank credit as witnessed today. It follows a massive covid-related spike when the US Government’s budget deficit soared. And its rise and fall is contemporaneous with a collapse in government revenues and soaring welfare costs.

In fiscal 2020 (to end-September), the Federal Government’s deficit was $3.312 trillion, compared with revenue of $3.42 trillion. It meant that spending was nearly twice tax income. Some of that excess expenditure was helicoptered directly into citizens’ bank accounts. The rest was reflected in bank balances as it was spent into public circulation by the government. Furthermore, from March 2020 the Fed commenced QE at the rate of $120bn per month, adding a total of $2.6 trillion in bank deposits by the end of fiscal 2021.

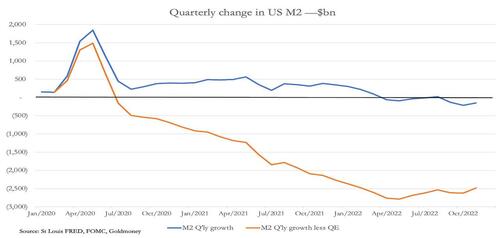

Deflating M2 by QE to get a feel for changes in the aggregate level of bank deposits strictly related to private sector origination tells us that private sector related credit was already contracting substantially in fiscal 2020—2021. This finding is consistent with an economy which suffered a suspension of much activity. This is illustrated in our next chart, taken from January 2020.

In this chart, accumulating QE is subtracted from official M2 to derive the red line. In practice, one cannot make such a clear distinction, because QE credit goes directly into the financial sector, which is broadly excluded from the GDP calculation. Nevertheless, QE inflates not just commercial bank reserves at the Fed, but their deposit liabilities to the insurance companies, pension funds, and other members of the shadow banking group. A minor portion of QE might relate to the commercial banks themselves, which for practical purposes can be ignored.

Through QE, state-origination of credit effectively crowds out private sector-origination of credit. A Keynesian critic might dismiss this on the basis that he believes QE stimulates the wider economy. That may be true when a monetary stimulus is first applied, since it takes time for market prices to adjust to the extra quantity of credit. Furthermore, QE stimulates financial market values and not the GDP economy, only affecting it later in a roundabout way.

But when QE eventually leaks out into the wider economy, it leads to higher prices for consumer goods, confirmed by the dramatic re-emergence of consumer price inflation. Furthermore, regulated banks are limited in their ability to create credit by balance sheet constraints, so to accommodate QE they are necessarily restricted in their credit creation for private sector borrowers.

Given the far larger quantities of non-bank credit which depend for its facilitation on bank credit, the negative impact on the economy of banks becoming risk averse is poorly understood. It is ignored on the assumption that state-origination of credit through budget deficits stimulates economic activity. What is less appreciated is that QE has already driven the non-government portion of the US economy into a deepening recession, yet to be reflected in government statistics. Furthermore, that the extra credit burden on the commercial banking system has exceeded their collective balance sheet capacity is confirmed by the Fed’s reverse repo facility, which offers deposit facilities additional to the commercial banking system. Currently standing at $2.2 trillion, it represents the bulk of excess credit created by QE since March 2020.

Adjusted for QE, the falling level of private sector deposits in the M2 statistic is consistent with an economic slump, only concealed statistically by the expansion of state spending and the loss of the dollar’s purchasing power. The economic distortions arising from QE are not restricted to America but are repeated in the other advanced economies as well. The only offset to the problem is an increase in private sector savings at the expense of immediate consumption and the extent to which they absorb increasing government borrowing. That way, the consequences for price inflation would have been lessened. But in America, much of the EU, and the UK, savings have not increased as a proportion of GDP, so there has been little or no savings offset to soaring budget deficits.

A funding crisis is in the making

Returning to the US as our primary example, we can see that national monetary statistics are concealing a slump in economic activity in the “real economy”. This real economy represents the state’s revenue base. On its own, this is going to lead to higher government borrowing than expected by forecasters as tax revenues fall and welfare commitments rise. And interest expense, already estimated by the Congressional Budget Office to cost $442bn in the current fiscal year and $525bn in fiscal 2024, are bound to be significantly higher due to unbudgeted extra borrowing.

Officialdom still assumes that a recession will be mild and brief. Consequently, the CBO’s calculations are unrealistic in what is clearly an unfolding economic slump given the evidence from bank credit. Even without considering additional negative factors, such as bankruptcies and bank failures which always attend a deep recession, borrowing cost estimates are almost certainly going to be far higher than currently expected.

In addition to domestic spending, the western alliance appears to be stepping up its war in Ukraine against Russia. US Defence spending is already running at nearly $800bn, and that can be expected to escalate significantly as the conflict in Ukraine worsens. The CBO’s estimate for 2024 is an increase to $814bn; but in the face of a more realistic assessment of an escalation of the Ukraine conflict since the CBO forecast was made last May, the outturn could easily be over $1,000bn.

To the volume of debt issuance must also be added variations in interest cost. Bond investors currently tolerate negative yields in the apparent belief that falling consumer demand in a recession will reduce the tendency for consumer prices to rise. This is certainly the official line in all western central banks. But as we have seen, this “transient inflation” argument has had its timescale pushed further into the future as reality intervenes.

This line of thinking, which is based on interpretations of supply and demand curves, ignores the plain fact that a general fall in consumption is tied irrevocably to a general fall in production. It also ignores the most important variable, which is the purchasing power of a fiat currency. It is the loss of purchasing power, which is primarily reflected in the consumer price index following the dilution of the currency by its debasement. In the absence of a sheet anchor tying credit values to legal money there is the thorny question of its users’ confidence being maintained in it as the exchange medium. Should that deteriorate, not only have we yet to see the consequences of earlier QE work their way through to undermining the dollar’s purchasing power, but the cost of government borrowing is likely to remain higher and for longer than official forecasts assume.

Funding difficulties are ahead

We can now identify sources of ongoing credit inflation, which at the least will serve to continue to undermine the dollar’s purchasing power and ensure that a rising trend for interest rates will continue. This conclusion is markedly different from expectations that the current catalogue of problems facing the US authorities amounts to a series of one-off factors that will diminish and disappear in time.

We can see that in common with the Eurozone, Japan, and the UK, the US financial system will be required to come up with rising levels of credit to fund government debt, the consequence of continuing high levels of budget deficits. Furthermore, after a brief respite from the exceptional levels of deficits over covid, there is every likelihood that these deficits will increase again, particularly in the US, UK, and the PIGS grouping in the Eurozone. Not only do these nations have a problem with budget deficits, but they have trade deficits as well. This is bad news particularly for the dollar and sterling, because both currencies are overly dependent on inward capital flows to balance their governments’ books.

It is becoming apparent that with respect to credit policies, the authorities in America (and the UK) are faced with mounting funding difficulties to resolve. We can briefly summarise them as follows:

-

Though they have yet to admit it, despite all the QE to date the evidence of a gathering recession is mounting. It has only served to conceal a deteriorating economic condition. The Fed is prioritising tackling rising consumer prices for now, claiming that that is the immediate problem.

-

Along with the US Treasury, the Fed still claims that inflation is transient. This claim must continue to have credibility if negative real yields in bond markets are to endure, a situation which cannot last for very long.

-

Monetary stimulus is confined by a lack of commercial banking balance sheet space. Further stimulation through QE will come up against this lack of headroom.

-

With early evidence of a declining foreign appetite for US Treasuries, it could become increasingly difficult to fund the government’s deficits, as was the case in the UK in the 1970s.

This author has vivid recollections of a similar situation faced by the UK’s monetary authorities between 1972—1975. In those days, the Bank of England was instructed in its monetary policy by the Treasury, and often its market related advice was overridden by Treasury mandarins lacking knowledge of financial markets. During the Barbour boom of 1971—1972, the Bank suppressed interest rates and encouraged the inflation of credit. Subsequently, price inflation started to rise and interest rates belatedly followed, always reluctantly conceded by the authorities.

This rapidly became a funding crisis for the government. The Treasury always tried to issue gilt-edged stock at less than the market was prepared to pay. Consequently, sterling’s exchange rate would come under pressure, and with a trend of rising consumer prices continuing, interest rates would have to be raised to get the gilt issue of the day subscribed. Having reflected a deteriorating situation, bond yields then fell when it was momentarily resolved. The crunch came in Autumn 1973, when the Bank of England’s minimum lending rate was increased from 9% on 26 July in steps to 13% on 13 November. A banking crisis suddenly ensued among lenders exposed to commercial property, and a number of banks failed. This episode became known as the secondary banking crisis.

As bond yields rose, stock markets crashed, with the FT30 Share Index falling from 530 in May 1972, to 140 in January 1975. The listed commercial property sector was virtually wiped out. In an air of crisis, inept Treasury policies continued to contribute to a growing fear of runaway inflation. Long maturity gilt issues bore coupons such as 15 ¼% and 15 ½%. And finally, in November 1976, the IMF bailed Britain out with a $3.9bn loan.

Today, these lessons for the Fed and holders of dollar denominated financial assets are instructive. Future increases in interest rates were always underestimated, and as the error became apparent bond yields rose and equities fell. While the Fed is notionally independent from the US Treasury, the Federal Open Market Committee’s approach to markets is one of control, which was not so much shared by the Bank of England in the 1970s but reflected the anti-market Keynesian view of the controlling UK Treasury.

In common with all other western central banks today, official policy at the Fed is to deny that price inflation is related to the quantity of credit. It is rare that money or credit in the context of a circulating medium is even mentioned in FOMC policy statements. Instead, interest rate setting is the dominant theme. And there is no acknowledgement that interest rates are primarily compensation to depositors for loss of purchasing power — a dangerous error when national finances are dependent on foreigners buying your treasury bonds.

Foreign ownership of dollars and dollar assets

In the 1970s, sterling’s troubles were compounded by a combination of trade deficits and Britain’s dependence on inward (foreign) investment. In short, the nation was, and still is savings deficient. Consequently, at the first sign of rising interest rates foreign holders recognised that the UK government would drag its heels at accepting reality. They would turn sellers leading to perennial sterling crises.

Today, the dollar has been protected from this fate because of its status as the world’s reserve currency. Otherwise, it shares the same characteristics as sterling in the 1970s — twin deficits, reliance upon foreign investment, and rising yields on government bonds.

According to the US Treasury’s TIC statistics, in the 12 months to September last, foreign holders purchased $846bn long-term securities. Breaking these figures down, private sector foreigners were net buyers, while foreign governments were net sellers. This reflects the difference between the trade deficit and the balance of payments: in other words, importers were retaining and investing most of their dollar payments on a net basis.

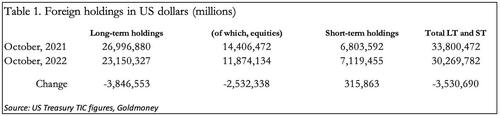

Table 1 shows the most recent position. Over the last year, the total value of foreign long-term and short-term investments in dollars (including bank deposits) fell by $3.531 trillion to $30.270 trillion. $2.532 trillion of this decline was in equity valuations, and with the recent rally in equity and bond markets, there will be some recovery in these numbers. But they are an indication of market and currency risks assumed by foreign holders of these assets if US bond yields start to rise again. And here we must also consider relative currency attractions.

The decline of the petrodollar and rise of the petroyuan

It is in this context that we must view Saudi Arabia’s move to replace petrodollars with petroyuan. Through its climate change policies, the western alliance against the Asian hegemons has effectively told its oil and natural gas supliers in the Gulf Cooperation Council that their carbon fuel products will no longer be welcome in a decade’s time. It is therefore hardly surprising that the Middle East sees its future trade being with China, along with her associates in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Eurasian economic Union, and the BRICS. Saudi Arabia has indicated her desire to join BRICS. Along with Egypt, Qatar, Emirates, Kuwait, and Bahrain, Saudi Arabia are also on the list to become dialog partners of the SCO.

Binding the membership of the SCO together is China’s plans to accelerate a communications and industrial revolution throughout Asia, and with a savings rate of 45% she has the capital available to invest in the necessary projects without undermining her currency. While America stagnates, China’s economy will be powering ahead.

There are further advantages to China’s plans with respect to the security and availability of cheap energy. While the Asians pay lip service to the western alliance’s insistence that fossil fuels must be reduced and then eliminated, in practice SCO members are still building coal-fired power stations and increasing their demand for all forms of fossil fuel. Members, associates, and dialog partners of the SCO, representing over 40% of the world’s population now include all the major oil and gas exporters in Asia.

The economic consequences are certain to impart significant advantages to China and her industrialisation plans, compared with the western alliance’s determination to starve itself of energy. While it will take some time for the Saudis to fully declare the petrodollar dead, the signal that she is prepared to accept petroyuan is an important one with more immediate consequences. We can be sure that besides geopolitical imperatives, the Saudis will have analysed the relative prospects between the two petro-currencies. They appear to have concluded that the risk of loss of the yuan’s purchasing power is at least no greater than that of the dollar. And if the Saudis are arriving at this conclusion, we can assume that other Asian governments holding dollars in their reserves will as well.

Russia is likely to stir the currency pot

With the western alliance increasing its support and involvement in the Ukraine proxy war, the military pressure on Russia is mounting. If President Putin has learned anything, it should be that military attempts to secure Eastern Ukraine carry a high risk of failure. Furthermore, with the alliance bringing more lethal weaponry to bear on his army, his prospects of military success are declining.

Compounding his military problems is the recent decline in oil and gas prices, particularly of the latter which has taken the energy squeeze off the EU. There can be little doubt that the greater these negative factors become, the greater the pressure on Putin to resort to a financial solution.

Putin’s strategy is likely to be simple and has already been telegraphed in his speech to the delegates at the St Petersburg Economic Forum last June. In short, he understands the weakness for the dollar’s position and by extension those of the other alliance currencies. Ideally, a cold snap in Middle and Eastern Europe will help lift oil and gas prices, increasing the prospects for price inflation, thereby bringing renewed pressure for interest rates in the alliance currencies to rise. This will lead to renewed losses on US and EU bonds, further falls in equities, and therefore dollar liquidation by foreigners. The eventual outcome of Triffin’s dilemma, a final crisis for the reserve currency, is certainly in the wings.

With the situation in Ukraine likely to escalate, Putin can ill afford to delay. On another front, he has authorised Russia’s National Wealth Fund to invest up to 60% in Chinese yuan and 40% in physical gold. This is probably a move to protect the fund from Putin’s view of future currency trends and from their declining value in gold. It is consistent with what the Saudis are doing with respect to getting out of dollars into yuan, and probably some gold bullion through the Shanghai International Gold Exchange. If this demand for gold extends beyond both Russia and Saudi Arabia, then the mechanism for dollar destruction could be accelerating demand for gold from multiple governments and entities in the Russian Chinese axis.

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

The evidence strongly suggests that a combined interest rate, economic and currency crisis for the US and its western alliance will continue in 2023.

This article focuses on credit, its constraints, and why quantitative easing has already crowded out private sector activity. Adjusting M2 money supply for accumulating QE indicates the degree to which this has driven the US tax base into deep recession. And the wider effects on credit in the economy should not be ignored.

After a brief partial recovery from the covid crisis in US government finances, they are likely to start deteriorating again due to a deepening recession of private sector activity. Funding these deficits depends on foreign inward investment flows, which are faltering. Rising interest rates and an ongoing bear market make funding from this source hard to envisage.

Meanwhile, from his public statements President Putin is fully aware of these difficulties, and a consequence of the western alliance increasing their support and involvement in Ukraine makes it almost certain that Putin will take the opportunity to push the dollar over the edge.

Credit is much more than bank deposits

Economics is about credit, and its balance sheet twin, debt. Debt is either productive, in which case it can extinguish credit in due course, or it is not, and credit must be extended or written off. Money almost never comes into it. Money is distinguished from credit by having no counterparty risk, which credit always has. The role of money is to stabilise the purchasing power of credit. And the only legal form of money is metallic; gold, silver, or copper usually rendered into coin for enhanced fungibility.

Credit is created between consenting parties. It facilitates commerce, created to circulate existing commodities, and to transform them into consumer goods. The chain of production requires credit, from miner, grower, or importer, to manufacturer, wholesaler, retailer and customer or consumer. Credit in the production chain is only extinguished when the customer or consumer pays for the end product. Until then, the entire production chain must either have money or arrange for credit to pay for their inputs.

Providers of this credit include the widest range of economic actors in an economy as well as the banks. When we talk of the misnamed money supply as the measure of credit in an economy, we are looking at the tip of an iceberg, leading us to think that debt in the form of bank notes and deposit accounts owed to individuals and businesses is the extent of it. Changes in the banking sector’s risk appetite drive a larger change in unrecorded credit conditions. We must accept that changes in the level of officially recognised debt are merely symptomatic of larger changes in payment obligations in the economy.

The role of credit is not adequately understood by economists. Keynes’s General Theory has only one indexed reference to credit in the entire book, the vade mecum for all macroeconomists. Even the title includes “money” when it is actually all about credit. Von Mises expounds on credit to a considerable degree in his Human Action, but this is an exception. And even his followers today are often unclear about the distinction between money and credit.

Economists and commentators have begun to understand that credit is not limited to banks, by admitting to the existence of shadow banking, a loose definition for financial institutions which do not have a banking licence but circulate credit. The Bank for International Settlements which monitors shadow banking appears to suspect shadow banks of creating credit without the requirement of a banking licence. There appears to be a confusion here: the BIS’s starting point is that credit is the preserve of a licenced bank. The mistake is to not understand the wider role of non-bank credit in economic activity.

But these institutions, ranging from insurance companies and pension funds to various forms of financial intermediaries and agents, unconsciously create credit by allowing time to elapse between a commitment giving rise to an obligation, and its settlement. Even next day settlement is a debt obligation for a buyer, or credit extended by a seller. Delivery against settlement is a credit obligation for both parties in a transaction. Futures, forwards, and options are credit obligations in favour of a buyer, which can be traded. And when a broker insists a client must have a credit in his account before investing, or to deliver securities before selling, credits and obligations are also created.

Therefore, credit has the same effect as money (which is very rarely used) in every transaction, financial or non-financial. All the debts in the accounts of businesses are part of the circulating medium in an economy, including bills of exchange and other tradable obligations. And at each transfer a new credit, debt, or right of action is created, while others are extinguished.

A banking system provides a base for further credit expansion because all credit transactions are ultimately settled in bank notes, which are an obligation of the note issuer (in practice today, a central bank) or through the novation of a bank deposit, being an obligation of a commercial bank. Banks are simply dealers in credit. As such, they facilitate not just their own dealings, but all credit creation and expunction.

The reason for making the point about the true extent of credit is that it is a mistake to think that the statistical expansion, or contraction of it, conventionally measured by the misnamed money supply, is the true extent of a change in outstanding credit. Central banks in particular act as if they believe that by influencing the height of the visible tip of the credit iceberg, they can simply ignore the consequences for the rest.

It is also worth making this point so that we can assess how the economies of the western alliance will fare in the year ahead — the American-led NATO and other nations adhering to its sphere of influence. With signs of bank credit no longer expanding and, in some cases, contracting, and with price inflation continuing at destructive levels and a recession threatened, it is rarely so important to understand credit and its role in an economy.

We also need to have a true understanding of credit to assess the prospects for China’s economy, which appears to be set on a different course. Emerging from lockdown and in the light of favourable geopolitical developments while the western alliance is tipping into recession, the prospects for China’s economy are rapidly improving.

Interest rates in 2023

That the long-term trend of declining interest rates for the major fiat currencies over the last four decades came to an end in 2021 is now beyond question. That this trend fostered a continuing appreciation of asset values is fundamental to an understanding of the consequences. And that the expansion of bank credit supporting a widening plethora of financial credit has stopped, is now only beginning to be register. If we look at the quarterly rate of change in US M2 money supply, this is now evident.

Since the Bretton Woods agreement was abandoned in 1971, there has not been as severe a contraction of US dollar bank credit as witnessed today. It follows a massive covid-related spike when the US Government’s budget deficit soared. And its rise and fall is contemporaneous with a collapse in government revenues and soaring welfare costs.

In fiscal 2020 (to end-September), the Federal Government’s deficit was $3.312 trillion, compared with revenue of $3.42 trillion. It meant that spending was nearly twice tax income. Some of that excess expenditure was helicoptered directly into citizens’ bank accounts. The rest was reflected in bank balances as it was spent into public circulation by the government. Furthermore, from March 2020 the Fed commenced QE at the rate of $120bn per month, adding a total of $2.6 trillion in bank deposits by the end of fiscal 2021.

Deflating M2 by QE to get a feel for changes in the aggregate level of bank deposits strictly related to private sector origination tells us that private sector related credit was already contracting substantially in fiscal 2020—2021. This finding is consistent with an economy which suffered a suspension of much activity. This is illustrated in our next chart, taken from January 2020.

In this chart, accumulating QE is subtracted from official M2 to derive the red line. In practice, one cannot make such a clear distinction, because QE credit goes directly into the financial sector, which is broadly excluded from the GDP calculation. Nevertheless, QE inflates not just commercial bank reserves at the Fed, but their deposit liabilities to the insurance companies, pension funds, and other members of the shadow banking group. A minor portion of QE might relate to the commercial banks themselves, which for practical purposes can be ignored.

Through QE, state-origination of credit effectively crowds out private sector-origination of credit. A Keynesian critic might dismiss this on the basis that he believes QE stimulates the wider economy. That may be true when a monetary stimulus is first applied, since it takes time for market prices to adjust to the extra quantity of credit. Furthermore, QE stimulates financial market values and not the GDP economy, only affecting it later in a roundabout way.

But when QE eventually leaks out into the wider economy, it leads to higher prices for consumer goods, confirmed by the dramatic re-emergence of consumer price inflation. Furthermore, regulated banks are limited in their ability to create credit by balance sheet constraints, so to accommodate QE they are necessarily restricted in their credit creation for private sector borrowers.

Given the far larger quantities of non-bank credit which depend for its facilitation on bank credit, the negative impact on the economy of banks becoming risk averse is poorly understood. It is ignored on the assumption that state-origination of credit through budget deficits stimulates economic activity. What is less appreciated is that QE has already driven the non-government portion of the US economy into a deepening recession, yet to be reflected in government statistics. Furthermore, that the extra credit burden on the commercial banking system has exceeded their collective balance sheet capacity is confirmed by the Fed’s reverse repo facility, which offers deposit facilities additional to the commercial banking system. Currently standing at $2.2 trillion, it represents the bulk of excess credit created by QE since March 2020.

Adjusted for QE, the falling level of private sector deposits in the M2 statistic is consistent with an economic slump, only concealed statistically by the expansion of state spending and the loss of the dollar’s purchasing power. The economic distortions arising from QE are not restricted to America but are repeated in the other advanced economies as well. The only offset to the problem is an increase in private sector savings at the expense of immediate consumption and the extent to which they absorb increasing government borrowing. That way, the consequences for price inflation would have been lessened. But in America, much of the EU, and the UK, savings have not increased as a proportion of GDP, so there has been little or no savings offset to soaring budget deficits.

A funding crisis is in the making

Returning to the US as our primary example, we can see that national monetary statistics are concealing a slump in economic activity in the “real economy”. This real economy represents the state’s revenue base. On its own, this is going to lead to higher government borrowing than expected by forecasters as tax revenues fall and welfare commitments rise. And interest expense, already estimated by the Congressional Budget Office to cost $442bn in the current fiscal year and $525bn in fiscal 2024, are bound to be significantly higher due to unbudgeted extra borrowing.

Officialdom still assumes that a recession will be mild and brief. Consequently, the CBO’s calculations are unrealistic in what is clearly an unfolding economic slump given the evidence from bank credit. Even without considering additional negative factors, such as bankruptcies and bank failures which always attend a deep recession, borrowing cost estimates are almost certainly going to be far higher than currently expected.

In addition to domestic spending, the western alliance appears to be stepping up its war in Ukraine against Russia. US Defence spending is already running at nearly $800bn, and that can be expected to escalate significantly as the conflict in Ukraine worsens. The CBO’s estimate for 2024 is an increase to $814bn; but in the face of a more realistic assessment of an escalation of the Ukraine conflict since the CBO forecast was made last May, the outturn could easily be over $1,000bn.

To the volume of debt issuance must also be added variations in interest cost. Bond investors currently tolerate negative yields in the apparent belief that falling consumer demand in a recession will reduce the tendency for consumer prices to rise. This is certainly the official line in all western central banks. But as we have seen, this “transient inflation” argument has had its timescale pushed further into the future as reality intervenes.

This line of thinking, which is based on interpretations of supply and demand curves, ignores the plain fact that a general fall in consumption is tied irrevocably to a general fall in production. It also ignores the most important variable, which is the purchasing power of a fiat currency. It is the loss of purchasing power, which is primarily reflected in the consumer price index following the dilution of the currency by its debasement. In the absence of a sheet anchor tying credit values to legal money there is the thorny question of its users’ confidence being maintained in it as the exchange medium. Should that deteriorate, not only have we yet to see the consequences of earlier QE work their way through to undermining the dollar’s purchasing power, but the cost of government borrowing is likely to remain higher and for longer than official forecasts assume.

Funding difficulties are ahead

We can now identify sources of ongoing credit inflation, which at the least will serve to continue to undermine the dollar’s purchasing power and ensure that a rising trend for interest rates will continue. This conclusion is markedly different from expectations that the current catalogue of problems facing the US authorities amounts to a series of one-off factors that will diminish and disappear in time.

We can see that in common with the Eurozone, Japan, and the UK, the US financial system will be required to come up with rising levels of credit to fund government debt, the consequence of continuing high levels of budget deficits. Furthermore, after a brief respite from the exceptional levels of deficits over covid, there is every likelihood that these deficits will increase again, particularly in the US, UK, and the PIGS grouping in the Eurozone. Not only do these nations have a problem with budget deficits, but they have trade deficits as well. This is bad news particularly for the dollar and sterling, because both currencies are overly dependent on inward capital flows to balance their governments’ books.

It is becoming apparent that with respect to credit policies, the authorities in America (and the UK) are faced with mounting funding difficulties to resolve. We can briefly summarise them as follows:

-

Though they have yet to admit it, despite all the QE to date the evidence of a gathering recession is mounting. It has only served to conceal a deteriorating economic condition. The Fed is prioritising tackling rising consumer prices for now, claiming that that is the immediate problem.

-

Along with the US Treasury, the Fed still claims that inflation is transient. This claim must continue to have credibility if negative real yields in bond markets are to endure, a situation which cannot last for very long.

-

Monetary stimulus is confined by a lack of commercial banking balance sheet space. Further stimulation through QE will come up against this lack of headroom.

-

With early evidence of a declining foreign appetite for US Treasuries, it could become increasingly difficult to fund the government’s deficits, as was the case in the UK in the 1970s.

This author has vivid recollections of a similar situation faced by the UK’s monetary authorities between 1972—1975. In those days, the Bank of England was instructed in its monetary policy by the Treasury, and often its market related advice was overridden by Treasury mandarins lacking knowledge of financial markets. During the Barbour boom of 1971—1972, the Bank suppressed interest rates and encouraged the inflation of credit. Subsequently, price inflation started to rise and interest rates belatedly followed, always reluctantly conceded by the authorities.

This rapidly became a funding crisis for the government. The Treasury always tried to issue gilt-edged stock at less than the market was prepared to pay. Consequently, sterling’s exchange rate would come under pressure, and with a trend of rising consumer prices continuing, interest rates would have to be raised to get the gilt issue of the day subscribed. Having reflected a deteriorating situation, bond yields then fell when it was momentarily resolved. The crunch came in Autumn 1973, when the Bank of England’s minimum lending rate was increased from 9% on 26 July in steps to 13% on 13 November. A banking crisis suddenly ensued among lenders exposed to commercial property, and a number of banks failed. This episode became known as the secondary banking crisis.

As bond yields rose, stock markets crashed, with the FT30 Share Index falling from 530 in May 1972, to 140 in January 1975. The listed commercial property sector was virtually wiped out. In an air of crisis, inept Treasury policies continued to contribute to a growing fear of runaway inflation. Long maturity gilt issues bore coupons such as 15 ¼% and 15 ½%. And finally, in November 1976, the IMF bailed Britain out with a $3.9bn loan.

Today, these lessons for the Fed and holders of dollar denominated financial assets are instructive. Future increases in interest rates were always underestimated, and as the error became apparent bond yields rose and equities fell. While the Fed is notionally independent from the US Treasury, the Federal Open Market Committee’s approach to markets is one of control, which was not so much shared by the Bank of England in the 1970s but reflected the anti-market Keynesian view of the controlling UK Treasury.

In common with all other western central banks today, official policy at the Fed is to deny that price inflation is related to the quantity of credit. It is rare that money or credit in the context of a circulating medium is even mentioned in FOMC policy statements. Instead, interest rate setting is the dominant theme. And there is no acknowledgement that interest rates are primarily compensation to depositors for loss of purchasing power — a dangerous error when national finances are dependent on foreigners buying your treasury bonds.

Foreign ownership of dollars and dollar assets

In the 1970s, sterling’s troubles were compounded by a combination of trade deficits and Britain’s dependence on inward (foreign) investment. In short, the nation was, and still is savings deficient. Consequently, at the first sign of rising interest rates foreign holders recognised that the UK government would drag its heels at accepting reality. They would turn sellers leading to perennial sterling crises.

Today, the dollar has been protected from this fate because of its status as the world’s reserve currency. Otherwise, it shares the same characteristics as sterling in the 1970s — twin deficits, reliance upon foreign investment, and rising yields on government bonds.

According to the US Treasury’s TIC statistics, in the 12 months to September last, foreign holders purchased $846bn long-term securities. Breaking these figures down, private sector foreigners were net buyers, while foreign governments were net sellers. This reflects the difference between the trade deficit and the balance of payments: in other words, importers were retaining and investing most of their dollar payments on a net basis.

Table 1 shows the most recent position. Over the last year, the total value of foreign long-term and short-term investments in dollars (including bank deposits) fell by $3.531 trillion to $30.270 trillion. $2.532 trillion of this decline was in equity valuations, and with the recent rally in equity and bond markets, there will be some recovery in these numbers. But they are an indication of market and currency risks assumed by foreign holders of these assets if US bond yields start to rise again. And here we must also consider relative currency attractions.

The decline of the petrodollar and rise of the petroyuan

It is in this context that we must view Saudi Arabia’s move to replace petrodollars with petroyuan. Through its climate change policies, the western alliance against the Asian hegemons has effectively told its oil and natural gas supliers in the Gulf Cooperation Council that their carbon fuel products will no longer be welcome in a decade’s time. It is therefore hardly surprising that the Middle East sees its future trade being with China, along with her associates in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Eurasian economic Union, and the BRICS. Saudi Arabia has indicated her desire to join BRICS. Along with Egypt, Qatar, Emirates, Kuwait, and Bahrain, Saudi Arabia are also on the list to become dialog partners of the SCO.

Binding the membership of the SCO together is China’s plans to accelerate a communications and industrial revolution throughout Asia, and with a savings rate of 45% she has the capital available to invest in the necessary projects without undermining her currency. While America stagnates, China’s economy will be powering ahead.

There are further advantages to China’s plans with respect to the security and availability of cheap energy. While the Asians pay lip service to the western alliance’s insistence that fossil fuels must be reduced and then eliminated, in practice SCO members are still building coal-fired power stations and increasing their demand for all forms of fossil fuel. Members, associates, and dialog partners of the SCO, representing over 40% of the world’s population now include all the major oil and gas exporters in Asia.

The economic consequences are certain to impart significant advantages to China and her industrialisation plans, compared with the western alliance’s determination to starve itself of energy. While it will take some time for the Saudis to fully declare the petrodollar dead, the signal that she is prepared to accept petroyuan is an important one with more immediate consequences. We can be sure that besides geopolitical imperatives, the Saudis will have analysed the relative prospects between the two petro-currencies. They appear to have concluded that the risk of loss of the yuan’s purchasing power is at least no greater than that of the dollar. And if the Saudis are arriving at this conclusion, we can assume that other Asian governments holding dollars in their reserves will as well.

Russia is likely to stir the currency pot

With the western alliance increasing its support and involvement in the Ukraine proxy war, the military pressure on Russia is mounting. If President Putin has learned anything, it should be that military attempts to secure Eastern Ukraine carry a high risk of failure. Furthermore, with the alliance bringing more lethal weaponry to bear on his army, his prospects of military success are declining.

Compounding his military problems is the recent decline in oil and gas prices, particularly of the latter which has taken the energy squeeze off the EU. There can be little doubt that the greater these negative factors become, the greater the pressure on Putin to resort to a financial solution.

Putin’s strategy is likely to be simple and has already been telegraphed in his speech to the delegates at the St Petersburg Economic Forum last June. In short, he understands the weakness for the dollar’s position and by extension those of the other alliance currencies. Ideally, a cold snap in Middle and Eastern Europe will help lift oil and gas prices, increasing the prospects for price inflation, thereby bringing renewed pressure for interest rates in the alliance currencies to rise. This will lead to renewed losses on US and EU bonds, further falls in equities, and therefore dollar liquidation by foreigners. The eventual outcome of Triffin’s dilemma, a final crisis for the reserve currency, is certainly in the wings.

With the situation in Ukraine likely to escalate, Putin can ill afford to delay. On another front, he has authorised Russia’s National Wealth Fund to invest up to 60% in Chinese yuan and 40% in physical gold. This is probably a move to protect the fund from Putin’s view of future currency trends and from their declining value in gold. It is consistent with what the Saudis are doing with respect to getting out of dollars into yuan, and probably some gold bullion through the Shanghai International Gold Exchange. If this demand for gold extends beyond both Russia and Saudi Arabia, then the mechanism for dollar destruction could be accelerating demand for gold from multiple governments and entities in the Russian Chinese axis.

Loading…