Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

There is a growing feeling in markets that a financial crisis of some sort is now on the cards. \

Credit Suisse’s very public struggles to refinance itself is proving to be a wake-up call for markets, alerting investors to the parlous state of global banking.

This article identifies the principal elements leading us into a global financial crisis.

Behind it all is the threat from a new trend of rising interest rates, and the natural desire of commercial banks everywhere to reduce their exposure to falling financial asset values both on their balance sheets and held as loan collateral.

And there are specific problems areas, which we can identify:

-

It should be noted that the phenomenal growth of OTC derivatives and regulated futures has been against a background of generally declining interest rates since the mid-eighties. That trend is now reversing, so we must expect the $600 trillion of global OTC derivatives and a further $100 trillion of futures to contract as banks reduce their derivative exposure. In the last two weeks, we have seen the consequences for the gilt market in London, warning us of other problem areas to come.

-

Commercial banks are over-leveraged, with notable weak spots in the Eurozone, Japan, and the UK. It will be something of a miracle if banks in these jurisdictions manage to survive contracting bank credit and derivative blow-ups. If they are not prevented, even the better capitalised American banks might not be safe.

-

Central banks are mandated to rescue the financial system in troubled times. However, we find that the ECB and its entire euro system of national central banks, the Bank of Japan, and the US Fed are all deeply in negative equity and in no condition to underwrite the financial system in this rising interest rate environment.

The Credit Suisse wake-up call

In the last fortnight, it has become obvious that Credit Suisse, one of Switzerland’s two major banking institutions, faces a radical restructuring. That’s probably a polite way of saying the bank needs rescuing.

In the hierarchy of Swiss banking, Credit Suisse used to be regarded as very conservative. The tables have now turned. Banks make bad decisions, and these can afflict any bank. Credit Suisse has perhaps been a little unfortunate, with the blow-up of Archegos, and Greensill Capital being very public errors. But surely the most egregious sin from a reputational point of view was a spying scandal, where the bank spied on its own employees. All the regulatory fines, universally regarded as a cost of business by bank executives, were weathered. But it was the spying scandal which forced the bank’s highly regarded CEO, Tidjane Thiam, to resign.

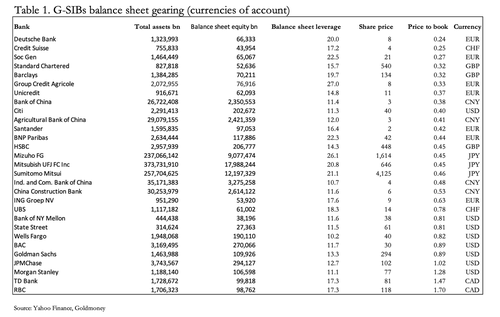

We must wish Credit Suisse’s hapless employees well in a period of high uncertainty for them. But this bank, one of thirty global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) is not alone in its difficulties. The only G-SIBs whose share capitalisation is greater than their balance sheet equity are North American: the two major Canadian banks, Morgan Stanley, and JPMorgan. The full list is shown in Table 1 below, ranked by price to book in the second to last column. [The French Bank, Groupe BPCE’s shares are unlisted so omitted from the table]

Before a sharp rally in the share price last week, Credit Suisse’s price to book stood at 24%, and Deutsche Bank’s stood at an equally lowly 23.5%. And as can be seen from the table, seventeen out of twenty-nine G-SIBs have price-to-book ratios of under 50%.

Normally, the opportunity to buy shares at book value or less is seen by value investors as a strategy for identifying undervalued investments. But when a whole sector is afflicted this way, the message is different. In the market valuations for these banks, their share prices signal a significant risk of failure, which is particularly acute in the European and UK majors, and to a similar but lesser extent in the three Japanese G-SIBs.

As a whole, G-SIBs have been valued in markets for the likelihood of systemic failure for some time. Despite what the markets have been signalling, these banks have survived, though as we have seen in the case of Deutsche Bank it has been a bumpy road for some. Regulations to improve balance sheet liquidity, mainly in the form of Basel 3, have been introduced in phases since the Lehman failure, and still price-to-book discounts have not recovered materially.

These depressed market valuations have made it impossible for the weaker G-SIBs to consider increasing their Tier 1 equity bases because of the dilutive effect on existing shareholders. Seeming to believe that their shares are undervalued, some banks have even been buying in discounted shares, reducing their capital and increasing balance sheet leverage even more. There is little doubt that in a very low interest rate environment some bankers reckoned this was the right thing to do.

But that has now changed. With interest rates now rising rapidly, over-leveraged balance sheets need to be urgently wound down to protect shareholders. And even bankers who have been so captured by the regulators that they regard their shareholders as a secondary priority will realise that their confrères in other banks will be selling down financial assets, liquidating financial collateral where possible, and withdrawing loan and overdraft facilities from non-financial businesses when they can.

It is all very well to complacently think that complying with Basel 3 liquidity provisions is a job well done. But if you ignore balance sheet leverage for your shareholders at a time of rising prices and therefore interest rates, they will almost certainly be wiped out. There can be no doubt that the change from an environment where price-to-book discounts are an irritation to bank executives to really mattering is bound up in a new, rising interest rate environment.

Rising interest rates are also a sea-change for derivatives, and particularly for the banks exposed to them. Interest rates swaps, of which the Bank for International Settlements reckoned there were $8.8 trillion equivalent in June 2021, have been deployed by pension funds, insurance companies, hedge funds and banks lending fixed-rate mortgages. They are turning out to be a financial instrument of mass destruction.

An interest rate swap is an arrangement between two counterparties who agree to exchange payments on a defined notional amount for a fixed time period. The notional amount is not exchanged, but interest rates on it are, one being at a predefined fixed rate such as a spread over a government bond yield with a maturity matching the duration of the swap agreement, while the other floats based on LIBOR or a similar yardstick.

Swaps can be agreed for fixed terms of up to fifteen years. When the yield curve is positive, a pension fund, for example, can obtain a decent income uplift by taking the fixed interest leg and paying the floating rate. And because the deal is based on notional capital, which is never put up, swaps can be leveraged significantly. The other party will be active in wholesale money markets, securing a small spread over floating rate payments received from the pension fund. Both counterparties expect to benefit from the deal, because their calculations of the net present values of the cash flows, which involves a degree of judgement, will not be too dissimilar when the deal is agreed.

The risk to the pension fund comes from rising bond yields. Despite the rise in bond yields, it still takes the fixed rate agreed at the outset, yet it is committed to paying a higher floating rate. In the UK, 3-month sterling LIBOR rose from 0.107% on 1 December 2021, to 3.94% yesterday. In a five-year swap, the fixed rate taken by the pension fund would be based on the 5-year gilt yield, which on 1 December last was 0.65%. With a spread of perhaps 0.25% over that, the pension fund would be taking 0.9% and paying 0.107%, for a turn of 0.793%. Today, the pension fund would still be taking 0.9%, but paying out 3.94%. With rising interest rates, even without leverage it is a disaster for the pension fund. But this is not the only trap they have fallen into.

In the UK, pension fund exposure to repurchase agreements (repos) led to margin calls and a sudden liquidation of gilt collateral less a fortnight ago. A number of specialist firms offered liability driven investment schemes (LDIs), targeted at final salary pension schemes. Using repos, LDI schemes were able to use low funding rates to finance long gilt positions, geared by up to seven times. When LDIs blew up due to falling collateral values, the gilt market collapsed as pension funds became forced sellers, and the Bank of England dramatically reversed its stillborn quantitative tightening policy. That saga has further to run, and the problem is not restricted to UK pension funds, as we shall see. A fuller description of how these repo schemes blew up is described later in this article.

The LDI episode is a warning of the consequences of a change in interest rate trends for derivatives in the widest sense. We should not forget that the evolution of derivatives has been in large measure due to the post-1980 trend of declining interest rates. With commodity, producer, and consumer prices now all rising fuelled by currency debasement, that trend has now come to an end. And with collateral values falling instead of rising, it is not just a case of dealers adjusting their outlook. There are bound to be more detonations in the $600 trillion OTC global derivatives market.

Central to these derivatives are banks and shadow banks. Credit Suisse has been a market maker in credit default swaps, leveraged loans, and other derivative-based activities. The bank deals in a wide range of swaps, interest rate and foreign exchange options, forex forwards and futures.[i] The replacement values of its OTC derivatives are shown in the 2021 accounts at CHF125.6 billion, which reduces with netting agreements to CHF25.6 billion. Small beer, it might seem. But the notional amounts, being the principal amounts upon which these derivative replacement values are based are far, far larger. The leverage between replacement values and notional amounts means that the bank’s exposure to rising interest rates could rapidly drive it into insolvency.

At this juncture, we cannot know if this is at the root of the bank’s troubles. And this article is not intended to be a criticism of Credit Suisse relative to its peers. The problems the bank faces are reflected in the entire G-SIB system with other banks having far larger derivative exposures. The point is that as a whole, participants in the derivatives market are unprepared for the conditions which led to its phenomenal growth at $600 trillion equivalent, which is now being reversed by a change in the primary trend for interest rates.

Central bank balance sheets and bailing commercial banks

In the event of commercial banking failures, it is generally expected that central banks will ensure depositors are protected, and that the financial system’s survival is guaranteed. But given the sheer size of derivative markets and the likely consequences of counterparty failures, it will be an enormous task requiring global cooperation and the abandonment of the bail-in procedures agreed by G20 member nations in the wake of the Lehman crisis. There will be no question but that failing banks must continue to trade with their bond holders’ funds remaining intact. If not, then all bank bonds are likely to collapse in value because in a bail-in bond holders will prefer the sanctity of deposits guaranteed by the state. And any attempt to limit deposit protection to smaller depositors would be disastrous.

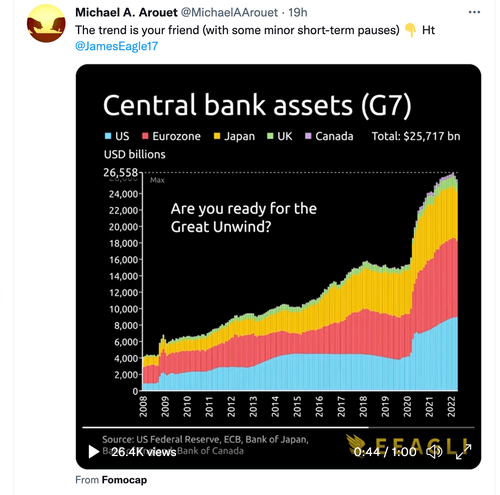

Because the Great Unwind is so sudden, it promises to become a far larger crisis than anything seen before. Unfortunately, due to quantitative easing the central banks themselves also have bond losses to contend with, wiping out the values of their balance sheet equity many times over. That a currency-issuing central bank has net liabilities on its balance sheet would not normally matter, because it can always expand credit to finance itself. But we are now envisaging central banks with substantial and growing net liabilities being required to guarantee entire commercial banking networks.

The burden of bail outs will undoubtedly lead to new rounds of currency debasement directly and indirectly, as vain attempts are made to support financial asset values and prevent an economic catastrophe. Accelerating currency debasement by the issuing authorities will almost certainly undermine public faith in fiat currencies, leading to their entire collapse, unless a way can be found to stabilise them.

The euro system has specific problems

In theory, recapitalising a central bank is a simple matter. The bank makes a loan to its shareholder, typically the government, which instead of a balancing deposit it books as equity in its liabilities. But when a central bank is not answerable to any government, that route cannot be taken.

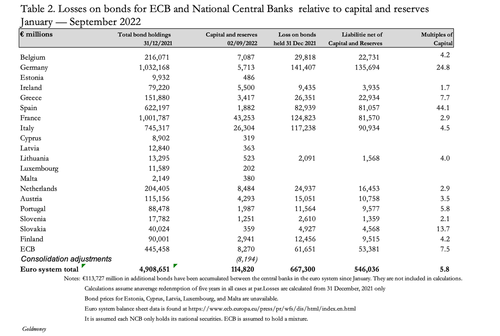

This is a problem for the ECB, whose shareholders are the national central banks of the member states. Unfortunately, they are also in need of recapitalisation. Table 2 below summarises the likely losses suffered this year so far on their bond holdings under the assumptions in the notes.

Other than the four national central banks for which bond prices are unavailable, we can see that all NCBs and the ECB itself have been entrapped by rising bond yields. Even the mighty Bundesbank appears to have losses on its bonds forty-four times its shareholders’ capital since 1 January. Bearing in mind that the Eurozone’s consumer price index is now rising at about 10% and considerably higher in some member states, 5-year maturity government bond yields between 2% (Germany) and 4% (Italy) can be expected to rise considerably from here. No amount of mollification, that central banks can never go bust, will cover up this problem.

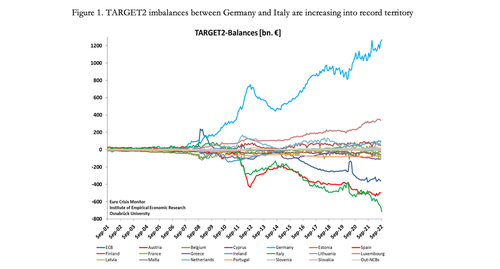

Imagine the legislative hurdles. The Bundesbank, let’s say, presents a case to the Bundestag to pass enabling legislation to permit it to recapitalise itself and to subscribe to more capital in the ECB on the basis of its share of the ECB’s equity to restore it to solvency. One can imagine finance ministers being persuaded that there is no alternative to the proposal, but then it will be noticed that the Bundesbank is owed over €1.2 trillion through the TARGET2 system. Surely, it will almost certainly be argued, if those liabilities were paid to the Bundesbank, there would be no need for it to recapitalise itself.

If only it were so simple. But clearly, it is not in the Bundesbank’s interest to involve ignorant politicians in monetary affairs. The public debate would risk spiralling out of control, with possibly fatal consequences for the entire euro system. So, what is happening with TARGET2?

TARGET2 imbalances are deteriorating again…

Figure 1 shows that TARGET2 imbalances are increasing again, notably for Germany’s Bundesbank, which is now owed a record €1,266,470 million, and Italy’s Banca Italia which owes €714,932 million. These are the figures for September, while all the others are for August and are yet to be updated.

In theory, these imbalances should not exist because that was an objective behind TARGET2’s construction. And before the Lehman crisis, they were minimal as the chart shows. Since then, they have increased to a total of €1,844,815 million, with Germany owed the most, followed by Luxembourg, which in August was owed €337,315 billion. Partly, this is due to Frankfurt and Luxembourg being financial centres for international transactions through which both foreign and Eurozone investing institutions have been selling euro-denominated obligations issued by entities in Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain (the PIGS). The bank credit resulting from these transactions works through the system as follows:

-

An Italian bond is sold through a German bank in Frankfurt. On delivering the bond, the seller has recorded in his favour a credit (deposit) at the German bank. Delivery to Milan against payment occurs with the settlement going through TARGET2, the settlement system through which cross-border settlements are made via the NCBs. Accordingly, the German bank records a matching credit (asset) with the Bundesbank.

-

The Bundesbank has a liability to the German bank. On the Bundesbank’s balance sheet, it generates a matching asset, reflecting the settlement due from the Banca d’Italia.

-

The Banca d’Italia has a liability to the Bundesbank, and a matching asset to the Italian bank acting for the buyer of the Italian bond.

-

The Italian bank has a liability to the Banca d’Italia, matching the debit on the bond buyer’s account, which is extinguishedby the buyer’s payment in settlement.

As far as the international seller and the buyer through the Italian market are concerned, settlement has occurred. But the offsetting transfers between the Bundesbank and the Banca d’Italia have not taken place. There have been no settlements between them, and imbalances are the result.

The situation has been worsened by capital flight within the Eurozone, using dodgy collateral originating in the PIGS posted to the relevant national central bank by commercial banks, against cash credits made to commercial banks in the form of repurchase agreements (repos).

There are two reasons for these repo transactions. The first is simple capital flight within the Eurozone, where cash balances gained through repos are deployed to buy bonds and other assets lodged in Germany and Luxembourg. The payments will be in euros but are very likely to be for bonds and other investments not denominated in euros. The second is that in overseeing TARGET2, the ECB has ignored collateral standards as a means of subsidising the PIGS’ financial systems.

With the PIGS economies on continuing life support, local bank regulators would be put in an awkward position if they had to decide whether bank loans are performing or non-performing. Because increasing quantities of these loans are undoubtedly non-performing, the solution has been to bundle them up as assets which can be used as collateral for repos through the central banks, so that they get lost in the TARGET2 system. If, say, the Banca d’Italia accepts the collateral it is no longer a concern for the local regulator.

The true fragility of the PIGS economies is concealed in this way, the precariousness of commercial bank finances is hidden, and the ECB has achieved a political objective of protecting the PIGS’ economies from collapse.

The recent increase in the imbalances, particularly between the Bundesbank and the Banca d’Italia are a warning that the system is breaking down. It was not an obvious problem when the long-term trend for interest rates was declining. But now that they are rising, the situation is radically different. The spread between Germany’s bond yields and those of Italy along with those of the other PIGS is increasingly being deemed by investors to be insufficient to compensate for the enhanced risks in a rising interest rate environment. The consequences could lead to a new crisis for the PIGS as their precarious state finances become undermined. Furthermore, capital flight out of Eurozone investments generally is confirmed by the collapse in the euro’s exchange rate against the US dollar.

The Eurozone’s repo market

From our analysis of the underlying causes of TARGET2 imbalances, we can see that repos play an important role. For the avoidance of doubt a repo is defined as a transaction agreed between parties to be reversed on pre-agreed terms at a future date. In exchange for posting collateral, a bank receives cash. The other party, in our discussion being a central bank, sees the same transaction as a reverse repo. It is a means of injecting fiat liquidity into the commercial banking system.

Repos and reverse repos are not exclusively used between commercial banks and central banks, but they are also undertaken between banks and other financial institutions, sometimes through third parties, including automated trading systems. They can be leveraged to produce enhanced returns, and this is one of the ways in which liability driven investment (LDI) has been used by UK pension funds geared up to seven times. Presumably UK LDIs are an activity mirrored by their Eurozone equivalents, likely to be revealed as interest rates continue to rise.

According to the last annual survey by the International Capital Market Association conducted in December 2021, at that time the size of the European repo market (including sterling, dollar, and other currencies conducted in European financial centres) stood at a record of €9,198 billion equivalent.[ii] This was based on responses from a sample of 57 institutions, including banks, so the true size of the market is somewhat larger. Measured by cash currency analysis, the euro share was 56.9% (€5,234bn).

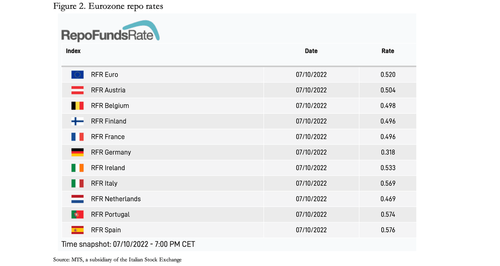

Obtaining euro cash through repos is cheap finance, as Figure 2 illustrates, which is of rates earlier this week.

It allows European pension and insurance funds to finance geared bond positions through liability driven investment schemes. Which is fine, until the values of the bonds held as collateral fall, and cash calls are then made. This is what blew up the UK gilt market recently and are doing do so again this week as gilt prices fall. This is not a problem restricted to the UK and sterling markets.

We can be sure that this situation is ringing alarm bells in the ECB’s headquarters in Frankfurt, as well as in all the major commercial banks around Europe. It has not been a concern so long as interest rates were not rising. Now that they are, with price inflation out of control there’s likely to be an increased reluctance on the part of the banks to novate repo agreements.

There are a number of moving parts to this emerging crisis. We can summarise the calamity beginning to overwhelm the Eurozone and the euro system, as follows:

-

Rising interest rates and bond yields are set to implode European repo markets. The LDI crisis which hit London will also afflict euro-denominated bond and repo markets — possibly even before the ink in this article has long dried.

-

Collapsing repos in turn will lead to a failure of the TARGET2 system, because repos are the primary mechanism drivingTARGET2 imbalances. The spreads between German and highly indebted PIGS government bonds are bound to widen dramatically, causing a new funding crisis for ever more highly indebted PIGS on a scale far larger than seen in the past.

-

Commercial banks in the Eurozone will be forced to liquidate their assets and collateral held against loans, including repos, as rapidly as possible. This will collapse Eurozone bond markets, as we saw with the UK gilt market earlier this month. Paper held in other currencies by Eurozone banks will be liquidated as well, spreading the crisis to other markets.

-

The ECB and the euro system, which is already insolvent, is duty bound to intervene heavily to support bond markets and ensure the survival of the whole system.

Panglossians might argue that the ECB has successfully managed financial crises in the past, and that to assume they will fail this time is unnecessarily alarmist. But the difference is in the trends for price inflation and interest rates. If the ECB is to have the slightest chance of succeeding in keeping the whole euro system and its allied commercial banking system afloat, it will be at the expense of the currency as it doubles down on suppressing interest rates.

The Bank of Japan is struggling to keep bond yields suppressed

Along with the ECB, the Bank of Japan forced negative interest rates upon its financial system in an effort to maintain a targeted 2% inflation rate. And while other jurisdictions see CPI rising at 10% or more, Japan’s CPI is rising at only 3%. There are a number of identifiable reasons why this is so. But the overriding reason is that the Japanese consumer continues to place unshakeable faith in the yen. This means that in the face of higher prices, the average consumer withholds spending, increasing preferences for holding the currency.

Even though the yen has fallen by 26% against the dollar, and dollar prices are rising at 8.5%, the growing preference for holding cash yen relative to consumer purchases in domestic markets holds. But this cannot go on for ever. While domestic market conditions remain stable, the US Fed’s more aggressive interest rate policy relative to the BOJ’s tells a different story for the yen on the foreign exchanges.

The Bank of Japan first started quantitative easing over twenty years ago and has accumulated a mixture of government bonds (JGBs), corporate bonds, equities through ETFs, and property trusts. On 30 September, their accumulated total had a book value — as distinct from a market value — of over ¥594 trillion ($4.1 trillion). But at ¥545.5 trillion, the JGB element is 92% 0f the total.

Since 31 December 2021, the yield on the 10-year JGB (by far the largest component) has risen from 0.17% to 0.25% today. On this basis, the bond portfolio held at that time has lost nearly ¥10 trillion, which compares with the bank’s capital of only ¥100 million. Therefore, the losses on the bond element alone are about 100,000 times greater that the bank’s slender equity.

One can see why the BOJ has drawn a line in the sand against market reality. It insists that the 10-year JGB yield must be prevented from rising above 0.25%. Its neo-Keynesian case is that consumer inflation is subdued so the case for reducing stimulation to the economy is a marginal one. But the consequence is that the currency is collapsing. And only yesterday, the rate to the US dollar began to slide again. This is shown in Figure 3 — note that a rising number represents a weakening yen.

Despite the mess that Japan’s Keynesian policies has created, it is difficult to see the BOJ changing course willingly. But the crisis for it will surely come if one or more of its three G-SIBs needs supporting. And it should be noted (See Table 1) that all three of them have balance sheet gearing measured by assets to shareholders equity of over twenty times, with Mizuho as much as 26 times, and they all have price to book ratios less than 50%.

The Fed’s position

The position of America’s Federal Reserve Board is starkly different from those of the other major central banks. True, it has substantial losses on its bond portfolio. In its Combined Quarterly Financial Report for June 30, 2022, the Fed disclosed the change in unrealised cumulative gains and losses on its Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities of $847,797 million loss (versus June 30 2021, $185,640m loss).[iii] The Fed reports these assets in its balance sheet at amortised cost, so the losses are not immediately apparent.

But on 30 June, the five-year note was yielding 2.7% and the ten-year 2.97%. Currently, they yield 4.16% and 3.95% respectively. Even without recalculating today’s market values, it is clear that the current deficit is now considerably more than a trillion dollars. And the Fed’s capital and reserves stand at only $46.274 billion, with portfolio losses exceding 25 times that figure.

Other than losses from rising bond yields, instead of pushing liquidity into markets it is withdrawing it through reverse repos. In this case, the Fed is swapping some of the bonds on its balance sheet for cash on pre-agreed, temporary terms. Officially, this is part of the Fed’s management of overnight interest rates. But with the reverse repo facility standing at over $2 trillion, this is far from a marginal rate setting activity. It probably has more to do with Basel 3 regulations which penalise large bank deposits relative to smaller deposits, and a lack of balance sheet capacity at the large US banks.

Repos, as opposed to reverse repos, still take place between individual banks and their institutional customers, but it is not obvious that they pose a systemic risk, though some large pension funds may have been using them for LDI transactions, similarly to the UK pension industry.

While highly geared compared with in the past, US G-SIBs are not nearly as much exposed to a general credit downturn as the Europeans, Japanese, and the British. Contracting bank credit will hurt them, but other G-SIBs are bound to fail first, transmitting systemic risk through counterparty relationships. Nevertheless, markets do recognise some risk, with price-to-book ratios of less than 0.9 for Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, State Street, and BONY-Mellon. JPMorgan Chase, which is the Fed’s principal policy conduit into the commercial banking system, is barely rated above book value.

Bank of England — bad policies but some smart operators

In the headlights of an oncoming gilt market crash, the Bank of England acted promptly to avert a crisis centred on pension fund liability driven investment involving interest rate swaps. The workings of interest rate swaps have already been described, but repos also played a role. It might be helpful to explain briefly how repos are used in the LDI context.

A pension fund goes to a shadow bank specialising in LDI schemes, with access to the repo market. In return for a deposit of say, 20% cash, the LDI scheme provider buys the full amount of medium and long-dated gilts to be held in the LDI scheme, using them as collateral backing for a repo to secure the funding for the other 80%. The repo can be for any duration from overnight to a year.

One year ago, when the Bank of England suppressed its bank rate at zero percent, one-month sterling LIBOR was close to 0.4% percent to borrow, while the yield on the 20-year gilt was 1.07%. Ignoring costs, a five-times leverage gave an interest rate turn of 0.63% X 5 = 3.15%, nearly three times the rate obtained by simply buying a 20-year gilt.

Today, the yield differential has improved, leading to even higher net returns. But the problem is that the rise in yield for the 20-year gilt to 4.9% means that the price has fallen from a notional 100 par to 49.95. Since this is the collateral for the cash obtained through the repo, the pension fund faces margin calls amounting to roughly 2.5 times the original investment in the LDI scheme. And all the pension funds using LDI schemes faced calls at the same time, which crashed the gilt market. This is why the BOE had to act quickly to stabilise prices.

Very sensibly, it has given pension funds and the LDI providers until this Friday to sort themselves out. Until then, the BOE stands prepared to buy any long-dated gilts until tomorrow (Friday, 14 October). It should remove the selling pressure from LDI-related liquidation entirely and orderly market conditions can then resume.

This experience serves as an example of how rising bond yields can wreak havoc in repo markets, and with interest rate swaps as well. That being the case, problems are bound to arise in other currency derivative markets as bond yields continue to rise.

Like the other major central banks, the BOE has seen a substantial deficit arise on its portfolio of gilts. But at the outset of QE, it got the Treasury to agree that as well as receiving the dividends and profits from gilts so acquired, it would also take any losses. All gilts bought under the QE programmes are held in a special purpose vehicle on the Bank’s balance sheet, guaranteed by the Treasury and therefore valued at cost.

Conclusions

In this article I have put to one side all the economic concerns of a downturn in the quantities of bank credit in circulation and focused on the financial consequences of a new long-term trend of rising interest rates. It should be coming clear that they threaten to undermine the entire fiat currency financial system.

Credit Suisse’s public problems should be considered in this context. That they have not arisen before was due to the successful suppression of interest rates and bond yields, while the quantities of currency and bank credit have expanded substantially without apparent ill effects. Those ill effects are now impacting financial markets by undermining the purchasing power of all fiat currencies at an accelerating rate.

From being completely in control of interest rates and fixed interest markets, central banks are now struggling in a losing battle to retain that control from the consequences of their earlier credit expansion. That enemy of every state, the market, has central banks on the run, uncertain as to whether their currencies should be protected (this is the Fed’s current decision and probably a dithering BOE) or a precarious financial system must be the priority (this is the ECB and BOJ’s current position).

But one thing is clear: with CPI measures rising at a 10% clip, interest rates and bond yields will continue to rise until something breaks. So far, commercial banks are dumping financial assets to deleverage their balance sheets. The effects on listed securities are in plain sight. What is less appreciated, at least before LDI schemes threatened to collapse the UK’s gilt market, is that the $600 trillion OTC derivative market which grew on the back of a long-term trend of declining interest rates is now set to shrink as contracts go sour and banks refuse to novate them. That means that up to $600 trillion of notional credit is set to vanish, in what we might call the Great Unwind.

This downturn in the cycle of bank credit boom and bust will prove difficult enough for the central banks to manage. But they themselves have balance sheet issues, which can only be resolved, one way or another, by the rapid expansion of base money. And that risks undermining all public credibility in fiat currencies.

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

There is a growing feeling in markets that a financial crisis of some sort is now on the cards. \

Credit Suisse’s very public struggles to refinance itself is proving to be a wake-up call for markets, alerting investors to the parlous state of global banking.

This article identifies the principal elements leading us into a global financial crisis.

Behind it all is the threat from a new trend of rising interest rates, and the natural desire of commercial banks everywhere to reduce their exposure to falling financial asset values both on their balance sheets and held as loan collateral.

And there are specific problems areas, which we can identify:

-

It should be noted that the phenomenal growth of OTC derivatives and regulated futures has been against a background of generally declining interest rates since the mid-eighties. That trend is now reversing, so we must expect the $600 trillion of global OTC derivatives and a further $100 trillion of futures to contract as banks reduce their derivative exposure. In the last two weeks, we have seen the consequences for the gilt market in London, warning us of other problem areas to come.

-

Commercial banks are over-leveraged, with notable weak spots in the Eurozone, Japan, and the UK. It will be something of a miracle if banks in these jurisdictions manage to survive contracting bank credit and derivative blow-ups. If they are not prevented, even the better capitalised American banks might not be safe.

-

Central banks are mandated to rescue the financial system in troubled times. However, we find that the ECB and its entire euro system of national central banks, the Bank of Japan, and the US Fed are all deeply in negative equity and in no condition to underwrite the financial system in this rising interest rate environment.

The Credit Suisse wake-up call

In the last fortnight, it has become obvious that Credit Suisse, one of Switzerland’s two major banking institutions, faces a radical restructuring. That’s probably a polite way of saying the bank needs rescuing.

In the hierarchy of Swiss banking, Credit Suisse used to be regarded as very conservative. The tables have now turned. Banks make bad decisions, and these can afflict any bank. Credit Suisse has perhaps been a little unfortunate, with the blow-up of Archegos, and Greensill Capital being very public errors. But surely the most egregious sin from a reputational point of view was a spying scandal, where the bank spied on its own employees. All the regulatory fines, universally regarded as a cost of business by bank executives, were weathered. But it was the spying scandal which forced the bank’s highly regarded CEO, Tidjane Thiam, to resign.

We must wish Credit Suisse’s hapless employees well in a period of high uncertainty for them. But this bank, one of thirty global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) is not alone in its difficulties. The only G-SIBs whose share capitalisation is greater than their balance sheet equity are North American: the two major Canadian banks, Morgan Stanley, and JPMorgan. The full list is shown in Table 1 below, ranked by price to book in the second to last column. [The French Bank, Groupe BPCE’s shares are unlisted so omitted from the table]

Before a sharp rally in the share price last week, Credit Suisse’s price to book stood at 24%, and Deutsche Bank’s stood at an equally lowly 23.5%. And as can be seen from the table, seventeen out of twenty-nine G-SIBs have price-to-book ratios of under 50%.

Normally, the opportunity to buy shares at book value or less is seen by value investors as a strategy for identifying undervalued investments. But when a whole sector is afflicted this way, the message is different. In the market valuations for these banks, their share prices signal a significant risk of failure, which is particularly acute in the European and UK majors, and to a similar but lesser extent in the three Japanese G-SIBs.

As a whole, G-SIBs have been valued in markets for the likelihood of systemic failure for some time. Despite what the markets have been signalling, these banks have survived, though as we have seen in the case of Deutsche Bank it has been a bumpy road for some. Regulations to improve balance sheet liquidity, mainly in the form of Basel 3, have been introduced in phases since the Lehman failure, and still price-to-book discounts have not recovered materially.

These depressed market valuations have made it impossible for the weaker G-SIBs to consider increasing their Tier 1 equity bases because of the dilutive effect on existing shareholders. Seeming to believe that their shares are undervalued, some banks have even been buying in discounted shares, reducing their capital and increasing balance sheet leverage even more. There is little doubt that in a very low interest rate environment some bankers reckoned this was the right thing to do.

But that has now changed. With interest rates now rising rapidly, over-leveraged balance sheets need to be urgently wound down to protect shareholders. And even bankers who have been so captured by the regulators that they regard their shareholders as a secondary priority will realise that their confrères in other banks will be selling down financial assets, liquidating financial collateral where possible, and withdrawing loan and overdraft facilities from non-financial businesses when they can.

It is all very well to complacently think that complying with Basel 3 liquidity provisions is a job well done. But if you ignore balance sheet leverage for your shareholders at a time of rising prices and therefore interest rates, they will almost certainly be wiped out. There can be no doubt that the change from an environment where price-to-book discounts are an irritation to bank executives to really mattering is bound up in a new, rising interest rate environment.

Rising interest rates are also a sea-change for derivatives, and particularly for the banks exposed to them. Interest rates swaps, of which the Bank for International Settlements reckoned there were $8.8 trillion equivalent in June 2021, have been deployed by pension funds, insurance companies, hedge funds and banks lending fixed-rate mortgages. They are turning out to be a financial instrument of mass destruction.

An interest rate swap is an arrangement between two counterparties who agree to exchange payments on a defined notional amount for a fixed time period. The notional amount is not exchanged, but interest rates on it are, one being at a predefined fixed rate such as a spread over a government bond yield with a maturity matching the duration of the swap agreement, while the other floats based on LIBOR or a similar yardstick.

Swaps can be agreed for fixed terms of up to fifteen years. When the yield curve is positive, a pension fund, for example, can obtain a decent income uplift by taking the fixed interest leg and paying the floating rate. And because the deal is based on notional capital, which is never put up, swaps can be leveraged significantly. The other party will be active in wholesale money markets, securing a small spread over floating rate payments received from the pension fund. Both counterparties expect to benefit from the deal, because their calculations of the net present values of the cash flows, which involves a degree of judgement, will not be too dissimilar when the deal is agreed.

The risk to the pension fund comes from rising bond yields. Despite the rise in bond yields, it still takes the fixed rate agreed at the outset, yet it is committed to paying a higher floating rate. In the UK, 3-month sterling LIBOR rose from 0.107% on 1 December 2021, to 3.94% yesterday. In a five-year swap, the fixed rate taken by the pension fund would be based on the 5-year gilt yield, which on 1 December last was 0.65%. With a spread of perhaps 0.25% over that, the pension fund would be taking 0.9% and paying 0.107%, for a turn of 0.793%. Today, the pension fund would still be taking 0.9%, but paying out 3.94%. With rising interest rates, even without leverage it is a disaster for the pension fund. But this is not the only trap they have fallen into.

In the UK, pension fund exposure to repurchase agreements (repos) led to margin calls and a sudden liquidation of gilt collateral less a fortnight ago. A number of specialist firms offered liability driven investment schemes (LDIs), targeted at final salary pension schemes. Using repos, LDI schemes were able to use low funding rates to finance long gilt positions, geared by up to seven times. When LDIs blew up due to falling collateral values, the gilt market collapsed as pension funds became forced sellers, and the Bank of England dramatically reversed its stillborn quantitative tightening policy. That saga has further to run, and the problem is not restricted to UK pension funds, as we shall see. A fuller description of how these repo schemes blew up is described later in this article.

The LDI episode is a warning of the consequences of a change in interest rate trends for derivatives in the widest sense. We should not forget that the evolution of derivatives has been in large measure due to the post-1980 trend of declining interest rates. With commodity, producer, and consumer prices now all rising fuelled by currency debasement, that trend has now come to an end. And with collateral values falling instead of rising, it is not just a case of dealers adjusting their outlook. There are bound to be more detonations in the $600 trillion OTC global derivatives market.

Central to these derivatives are banks and shadow banks. Credit Suisse has been a market maker in credit default swaps, leveraged loans, and other derivative-based activities. The bank deals in a wide range of swaps, interest rate and foreign exchange options, forex forwards and futures.[i] The replacement values of its OTC derivatives are shown in the 2021 accounts at CHF125.6 billion, which reduces with netting agreements to CHF25.6 billion. Small beer, it might seem. But the notional amounts, being the principal amounts upon which these derivative replacement values are based are far, far larger. The leverage between replacement values and notional amounts means that the bank’s exposure to rising interest rates could rapidly drive it into insolvency.

At this juncture, we cannot know if this is at the root of the bank’s troubles. And this article is not intended to be a criticism of Credit Suisse relative to its peers. The problems the bank faces are reflected in the entire G-SIB system with other banks having far larger derivative exposures. The point is that as a whole, participants in the derivatives market are unprepared for the conditions which led to its phenomenal growth at $600 trillion equivalent, which is now being reversed by a change in the primary trend for interest rates.

Central bank balance sheets and bailing commercial banks

In the event of commercial banking failures, it is generally expected that central banks will ensure depositors are protected, and that the financial system’s survival is guaranteed. But given the sheer size of derivative markets and the likely consequences of counterparty failures, it will be an enormous task requiring global cooperation and the abandonment of the bail-in procedures agreed by G20 member nations in the wake of the Lehman crisis. There will be no question but that failing banks must continue to trade with their bond holders’ funds remaining intact. If not, then all bank bonds are likely to collapse in value because in a bail-in bond holders will prefer the sanctity of deposits guaranteed by the state. And any attempt to limit deposit protection to smaller depositors would be disastrous.

Because the Great Unwind is so sudden, it promises to become a far larger crisis than anything seen before. Unfortunately, due to quantitative easing the central banks themselves also have bond losses to contend with, wiping out the values of their balance sheet equity many times over. That a currency-issuing central bank has net liabilities on its balance sheet would not normally matter, because it can always expand credit to finance itself. But we are now envisaging central banks with substantial and growing net liabilities being required to guarantee entire commercial banking networks.

The burden of bail outs will undoubtedly lead to new rounds of currency debasement directly and indirectly, as vain attempts are made to support financial asset values and prevent an economic catastrophe. Accelerating currency debasement by the issuing authorities will almost certainly undermine public faith in fiat currencies, leading to their entire collapse, unless a way can be found to stabilise them.

The euro system has specific problems

In theory, recapitalising a central bank is a simple matter. The bank makes a loan to its shareholder, typically the government, which instead of a balancing deposit it books as equity in its liabilities. But when a central bank is not answerable to any government, that route cannot be taken.

This is a problem for the ECB, whose shareholders are the national central banks of the member states. Unfortunately, they are also in need of recapitalisation. Table 2 below summarises the likely losses suffered this year so far on their bond holdings under the assumptions in the notes.

Other than the four national central banks for which bond prices are unavailable, we can see that all NCBs and the ECB itself have been entrapped by rising bond yields. Even the mighty Bundesbank appears to have losses on its bonds forty-four times its shareholders’ capital since 1 January. Bearing in mind that the Eurozone’s consumer price index is now rising at about 10% and considerably higher in some member states, 5-year maturity government bond yields between 2% (Germany) and 4% (Italy) can be expected to rise considerably from here. No amount of mollification, that central banks can never go bust, will cover up this problem.

Imagine the legislative hurdles. The Bundesbank, let’s say, presents a case to the Bundestag to pass enabling legislation to permit it to recapitalise itself and to subscribe to more capital in the ECB on the basis of its share of the ECB’s equity to restore it to solvency. One can imagine finance ministers being persuaded that there is no alternative to the proposal, but then it will be noticed that the Bundesbank is owed over €1.2 trillion through the TARGET2 system. Surely, it will almost certainly be argued, if those liabilities were paid to the Bundesbank, there would be no need for it to recapitalise itself.

If only it were so simple. But clearly, it is not in the Bundesbank’s interest to involve ignorant politicians in monetary affairs. The public debate would risk spiralling out of control, with possibly fatal consequences for the entire euro system. So, what is happening with TARGET2?

TARGET2 imbalances are deteriorating again…

Figure 1 shows that TARGET2 imbalances are increasing again, notably for Germany’s Bundesbank, which is now owed a record €1,266,470 million, and Italy’s Banca Italia which owes €714,932 million. These are the figures for September, while all the others are for August and are yet to be updated.

In theory, these imbalances should not exist because that was an objective behind TARGET2’s construction. And before the Lehman crisis, they were minimal as the chart shows. Since then, they have increased to a total of €1,844,815 million, with Germany owed the most, followed by Luxembourg, which in August was owed €337,315 billion. Partly, this is due to Frankfurt and Luxembourg being financial centres for international transactions through which both foreign and Eurozone investing institutions have been selling euro-denominated obligations issued by entities in Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain (the PIGS). The bank credit resulting from these transactions works through the system as follows:

-

An Italian bond is sold through a German bank in Frankfurt. On delivering the bond, the seller has recorded in his favour a credit (deposit) at the German bank. Delivery to Milan against payment occurs with the settlement going through TARGET2, the settlement system through which cross-border settlements are made via the NCBs. Accordingly, the German bank records a matching credit (asset) with the Bundesbank.

-

The Bundesbank has a liability to the German bank. On the Bundesbank’s balance sheet, it generates a matching asset, reflecting the settlement due from the Banca d’Italia.

-

The Banca d’Italia has a liability to the Bundesbank, and a matching asset to the Italian bank acting for the buyer of the Italian bond.

-

The Italian bank has a liability to the Banca d’Italia, matching the debit on the bond buyer’s account, which is extinguishedby the buyer’s payment in settlement.

As far as the international seller and the buyer through the Italian market are concerned, settlement has occurred. But the offsetting transfers between the Bundesbank and the Banca d’Italia have not taken place. There have been no settlements between them, and imbalances are the result.

The situation has been worsened by capital flight within the Eurozone, using dodgy collateral originating in the PIGS posted to the relevant national central bank by commercial banks, against cash credits made to commercial banks in the form of repurchase agreements (repos).

There are two reasons for these repo transactions. The first is simple capital flight within the Eurozone, where cash balances gained through repos are deployed to buy bonds and other assets lodged in Germany and Luxembourg. The payments will be in euros but are very likely to be for bonds and other investments not denominated in euros. The second is that in overseeing TARGET2, the ECB has ignored collateral standards as a means of subsidising the PIGS’ financial systems.

With the PIGS economies on continuing life support, local bank regulators would be put in an awkward position if they had to decide whether bank loans are performing or non-performing. Because increasing quantities of these loans are undoubtedly non-performing, the solution has been to bundle them up as assets which can be used as collateral for repos through the central banks, so that they get lost in the TARGET2 system. If, say, the Banca d’Italia accepts the collateral it is no longer a concern for the local regulator.

The true fragility of the PIGS economies is concealed in this way, the precariousness of commercial bank finances is hidden, and the ECB has achieved a political objective of protecting the PIGS’ economies from collapse.

The recent increase in the imbalances, particularly between the Bundesbank and the Banca d’Italia are a warning that the system is breaking down. It was not an obvious problem when the long-term trend for interest rates was declining. But now that they are rising, the situation is radically different. The spread between Germany’s bond yields and those of Italy along with those of the other PIGS is increasingly being deemed by investors to be insufficient to compensate for the enhanced risks in a rising interest rate environment. The consequences could lead to a new crisis for the PIGS as their precarious state finances become undermined. Furthermore, capital flight out of Eurozone investments generally is confirmed by the collapse in the euro’s exchange rate against the US dollar.

The Eurozone’s repo market

From our analysis of the underlying causes of TARGET2 imbalances, we can see that repos play an important role. For the avoidance of doubt a repo is defined as a transaction agreed between parties to be reversed on pre-agreed terms at a future date. In exchange for posting collateral, a bank receives cash. The other party, in our discussion being a central bank, sees the same transaction as a reverse repo. It is a means of injecting fiat liquidity into the commercial banking system.

Repos and reverse repos are not exclusively used between commercial banks and central banks, but they are also undertaken between banks and other financial institutions, sometimes through third parties, including automated trading systems. They can be leveraged to produce enhanced returns, and this is one of the ways in which liability driven investment (LDI) has been used by UK pension funds geared up to seven times. Presumably UK LDIs are an activity mirrored by their Eurozone equivalents, likely to be revealed as interest rates continue to rise.

According to the last annual survey by the International Capital Market Association conducted in December 2021, at that time the size of the European repo market (including sterling, dollar, and other currencies conducted in European financial centres) stood at a record of €9,198 billion equivalent.[ii] This was based on responses from a sample of 57 institutions, including banks, so the true size of the market is somewhat larger. Measured by cash currency analysis, the euro share was 56.9% (€5,234bn).

Obtaining euro cash through repos is cheap finance, as Figure 2 illustrates, which is of rates earlier this week.

It allows European pension and insurance funds to finance geared bond positions through liability driven investment schemes. Which is fine, until the values of the bonds held as collateral fall, and cash calls are then made. This is what blew up the UK gilt market recently and are doing do so again this week as gilt prices fall. This is not a problem restricted to the UK and sterling markets.

We can be sure that this situation is ringing alarm bells in the ECB’s headquarters in Frankfurt, as well as in all the major commercial banks around Europe. It has not been a concern so long as interest rates were not rising. Now that they are, with price inflation out of control there’s likely to be an increased reluctance on the part of the banks to novate repo agreements.

There are a number of moving parts to this emerging crisis. We can summarise the calamity beginning to overwhelm the Eurozone and the euro system, as follows:

-

Rising interest rates and bond yields are set to implode European repo markets. The LDI crisis which hit London will also afflict euro-denominated bond and repo markets — possibly even before the ink in this article has long dried.

-

Collapsing repos in turn will lead to a failure of the TARGET2 system, because repos are the primary mechanism drivingTARGET2 imbalances. The spreads between German and highly indebted PIGS government bonds are bound to widen dramatically, causing a new funding crisis for ever more highly indebted PIGS on a scale far larger than seen in the past.

-

Commercial banks in the Eurozone will be forced to liquidate their assets and collateral held against loans, including repos, as rapidly as possible. This will collapse Eurozone bond markets, as we saw with the UK gilt market earlier this month. Paper held in other currencies by Eurozone banks will be liquidated as well, spreading the crisis to other markets.

-

The ECB and the euro system, which is already insolvent, is duty bound to intervene heavily to support bond markets and ensure the survival of the whole system.

Panglossians might argue that the ECB has successfully managed financial crises in the past, and that to assume they will fail this time is unnecessarily alarmist. But the difference is in the trends for price inflation and interest rates. If the ECB is to have the slightest chance of succeeding in keeping the whole euro system and its allied commercial banking system afloat, it will be at the expense of the currency as it doubles down on suppressing interest rates.

The Bank of Japan is struggling to keep bond yields suppressed

Along with the ECB, the Bank of Japan forced negative interest rates upon its financial system in an effort to maintain a targeted 2% inflation rate. And while other jurisdictions see CPI rising at 10% or more, Japan’s CPI is rising at only 3%. There are a number of identifiable reasons why this is so. But the overriding reason is that the Japanese consumer continues to place unshakeable faith in the yen. This means that in the face of higher prices, the average consumer withholds spending, increasing preferences for holding the currency.

Even though the yen has fallen by 26% against the dollar, and dollar prices are rising at 8.5%, the growing preference for holding cash yen relative to consumer purchases in domestic markets holds. But this cannot go on for ever. While domestic market conditions remain stable, the US Fed’s more aggressive interest rate policy relative to the BOJ’s tells a different story for the yen on the foreign exchanges.

The Bank of Japan first started quantitative easing over twenty years ago and has accumulated a mixture of government bonds (JGBs), corporate bonds, equities through ETFs, and property trusts. On 30 September, their accumulated total had a book value — as distinct from a market value — of over ¥594 trillion ($4.1 trillion). But at ¥545.5 trillion, the JGB element is 92% 0f the total.

Since 31 December 2021, the yield on the 10-year JGB (by far the largest component) has risen from 0.17% to 0.25% today. On this basis, the bond portfolio held at that time has lost nearly ¥10 trillion, which compares with the bank’s capital of only ¥100 million. Therefore, the losses on the bond element alone are about 100,000 times greater that the bank’s slender equity.

One can see why the BOJ has drawn a line in the sand against market reality. It insists that the 10-year JGB yield must be prevented from rising above 0.25%. Its neo-Keynesian case is that consumer inflation is subdued so the case for reducing stimulation to the economy is a marginal one. But the consequence is that the currency is collapsing. And only yesterday, the rate to the US dollar began to slide again. This is shown in Figure 3 — note that a rising number represents a weakening yen.

Despite the mess that Japan’s Keynesian policies has created, it is difficult to see the BOJ changing course willingly. But the crisis for it will surely come if one or more of its three G-SIBs needs supporting. And it should be noted (See Table 1) that all three of them have balance sheet gearing measured by assets to shareholders equity of over twenty times, with Mizuho as much as 26 times, and they all have price to book ratios less than 50%.

The Fed’s position

The position of America’s Federal Reserve Board is starkly different from those of the other major central banks. True, it has substantial losses on its bond portfolio. In its Combined Quarterly Financial Report for June 30, 2022, the Fed disclosed the change in unrealised cumulative gains and losses on its Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities of $847,797 million loss (versus June 30 2021, $185,640m loss).[iii] The Fed reports these assets in its balance sheet at amortised cost, so the losses are not immediately apparent.

But on 30 June, the five-year note was yielding 2.7% and the ten-year 2.97%. Currently, they yield 4.16% and 3.95% respectively. Even without recalculating today’s market values, it is clear that the current deficit is now considerably more than a trillion dollars. And the Fed’s capital and reserves stand at only $46.274 billion, with portfolio losses exceding 25 times that figure.

Other than losses from rising bond yields, instead of pushing liquidity into markets it is withdrawing it through reverse repos. In this case, the Fed is swapping some of the bonds on its balance sheet for cash on pre-agreed, temporary terms. Officially, this is part of the Fed’s management of overnight interest rates. But with the reverse repo facility standing at over $2 trillion, this is far from a marginal rate setting activity. It probably has more to do with Basel 3 regulations which penalise large bank deposits relative to smaller deposits, and a lack of balance sheet capacity at the large US banks.

Repos, as opposed to reverse repos, still take place between individual banks and their institutional customers, but it is not obvious that they pose a systemic risk, though some large pension funds may have been using them for LDI transactions, similarly to the UK pension industry.

While highly geared compared with in the past, US G-SIBs are not nearly as much exposed to a general credit downturn as the Europeans, Japanese, and the British. Contracting bank credit will hurt them, but other G-SIBs are bound to fail first, transmitting systemic risk through counterparty relationships. Nevertheless, markets do recognise some risk, with price-to-book ratios of less than 0.9 for Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, State Street, and BONY-Mellon. JPMorgan Chase, which is the Fed’s principal policy conduit into the commercial banking system, is barely rated above book value.

Bank of England — bad policies but some smart operators

In the headlights of an oncoming gilt market crash, the Bank of England acted promptly to avert a crisis centred on pension fund liability driven investment involving interest rate swaps. The workings of interest rate swaps have already been described, but repos also played a role. It might be helpful to explain briefly how repos are used in the LDI context.

A pension fund goes to a shadow bank specialising in LDI schemes, with access to the repo market. In return for a deposit of say, 20% cash, the LDI scheme provider buys the full amount of medium and long-dated gilts to be held in the LDI scheme, using them as collateral backing for a repo to secure the funding for the other 80%. The repo can be for any duration from overnight to a year.

One year ago, when the Bank of England suppressed its bank rate at zero percent, one-month sterling LIBOR was close to 0.4% percent to borrow, while the yield on the 20-year gilt was 1.07%. Ignoring costs, a five-times leverage gave an interest rate turn of 0.63% X 5 = 3.15%, nearly three times the rate obtained by simply buying a 20-year gilt.

Today, the yield differential has improved, leading to even higher net returns. But the problem is that the rise in yield for the 20-year gilt to 4.9% means that the price has fallen from a notional 100 par to 49.95. Since this is the collateral for the cash obtained through the repo, the pension fund faces margin calls amounting to roughly 2.5 times the original investment in the LDI scheme. And all the pension funds using LDI schemes faced calls at the same time, which crashed the gilt market. This is why the BOE had to act quickly to stabilise prices.

Very sensibly, it has given pension funds and the LDI providers until this Friday to sort themselves out. Until then, the BOE stands prepared to buy any long-dated gilts until tomorrow (Friday, 14 October). It should remove the selling pressure from LDI-related liquidation entirely and orderly market conditions can then resume.

This experience serves as an example of how rising bond yields can wreak havoc in repo markets, and with interest rate swaps as well. That being the case, problems are bound to arise in other currency derivative markets as bond yields continue to rise.

Like the other major central banks, the BOE has seen a substantial deficit arise on its portfolio of gilts. But at the outset of QE, it got the Treasury to agree that as well as receiving the dividends and profits from gilts so acquired, it would also take any losses. All gilts bought under the QE programmes are held in a special purpose vehicle on the Bank’s balance sheet, guaranteed by the Treasury and therefore valued at cost.

Conclusions

In this article I have put to one side all the economic concerns of a downturn in the quantities of bank credit in circulation and focused on the financial consequences of a new long-term trend of rising interest rates. It should be coming clear that they threaten to undermine the entire fiat currency financial system.

Credit Suisse’s public problems should be considered in this context. That they have not arisen before was due to the successful suppression of interest rates and bond yields, while the quantities of currency and bank credit have expanded substantially without apparent ill effects. Those ill effects are now impacting financial markets by undermining the purchasing power of all fiat currencies at an accelerating rate.

From being completely in control of interest rates and fixed interest markets, central banks are now struggling in a losing battle to retain that control from the consequences of their earlier credit expansion. That enemy of every state, the market, has central banks on the run, uncertain as to whether their currencies should be protected (this is the Fed’s current decision and probably a dithering BOE) or a precarious financial system must be the priority (this is the ECB and BOJ’s current position).

But one thing is clear: with CPI measures rising at a 10% clip, interest rates and bond yields will continue to rise until something breaks. So far, commercial banks are dumping financial assets to deleverage their balance sheets. The effects on listed securities are in plain sight. What is less appreciated, at least before LDI schemes threatened to collapse the UK’s gilt market, is that the $600 trillion OTC derivative market which grew on the back of a long-term trend of declining interest rates is now set to shrink as contracts go sour and banks refuse to novate them. That means that up to $600 trillion of notional credit is set to vanish, in what we might call the Great Unwind.

This downturn in the cycle of bank credit boom and bust will prove difficult enough for the central banks to manage. But they themselves have balance sheet issues, which can only be resolved, one way or another, by the rapid expansion of base money. And that risks undermining all public credibility in fiat currencies.