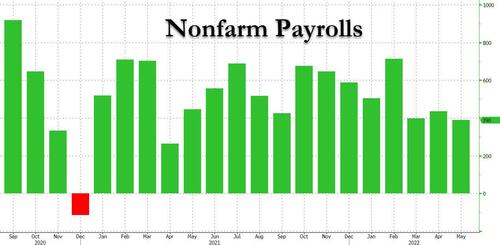

Heading into today's key payrolls print, we had a feeling that contrary to Wall Street's generally cheerful expectations, the jobs number would be bad based on dismal real-time indicators (as described in "We Could See A Million Layoffs Or More" - Here Comes The Job Market Shock), and the latest Goldman macro data, and we... were off, because moments ago the BLS reported that in May the US added 390K jobs, which was a drop from last month's upward revised 436K and the lowest since April 2021, but was well above the 320K expected (and once again made a mockery of the recent dismal ADP prints, which suggests that there was another political component here in the BLS data where someone likely made a phone call or two).

The change in total nonfarm payroll employment for March was revised down by 30,000, from +428,000 to +398,000, and the change for April was revised up by 8,000, from +428,000 to +436,000. With these revisions, employment in March and April combined is 22,000 lower than previously reported.

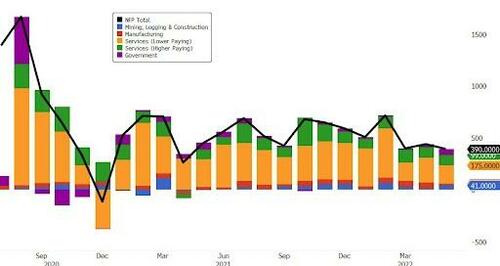

Breaking down the jobs, we see that in May, lower-paying 175K service jobs were added, down notably from 273K a month earlier, while higher-paying service jobs were unchanged at 99K; manufacturing jobs collapsed to 18K from 61K, offset by a surge in minind and logging jobs to 41K. 57K government jobs rounded out the picture.

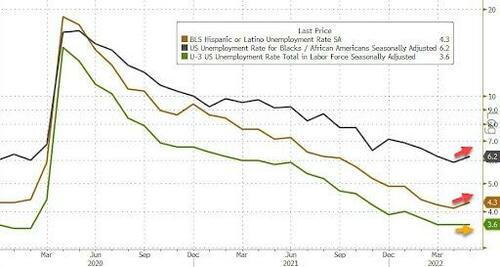

The unemployment rate was unchanged at 3.6%, and missed expectations of a drop to 3.5%, which would have been the lowest print since the covid crisis.

Among the major worker groups, the unemployment rate for Asians declined to 2.4 percent in May. The jobless rates for adult men (3.4 percent), adult women (3.4 percent), teenagers (10.4 percent), Whites (3.2 percent), Blacks (6.2 percent), and Hispanics (4.3 percent) showed little or no change over the month.

Some more details on the composition of unemployed workers:

- Among the unemployed, the number of permanent job losers remained at 1.4 million in May. The number of persons on temporary layoff was little changed at 810,000. Both measures are little different from their values in February 2020

- The number of long-term unemployed (those jobless for 27 weeks or more) edged down to 1.4 million. This measure is 235,000 higher than in February 2020. The long-term unemployed accounted for 23.2 percent of all unemployed persons in May

- The number of persons employed part time for economic reasons increased by 295,000 to 4.3 million in May, reflecting an increase in the number of persons whose hours were cut due to slack work or business conditions. The number of persons employed part time for economic reasons is little different from its February 2020 level. These individuals, who would have preferred full-time employment, were working part time because their hours had been reduced or they were unable to find full-time jobs.

- The number of persons not in the labor force who currently want a job was little changed at 5.7 million in May. This measure remains above its February 2020 level of 5.0 million. These individuals were not counted as unemployed because they were not actively looking for work during the 4 weeks preceding the survey or were unavailable to take a job

- Among those not in the labor force who wanted a job, the number of persons marginally attached to the labor force, at 1.5 million, changed little in May. These individuals wanted and were available for work and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months but had not looked for work in the 4 weeks preceding the survey. Discouraged workers, a subset of the marginally attached who believed that no jobs were available for them, numbered 415,000 in May, also little changed from the prior month.

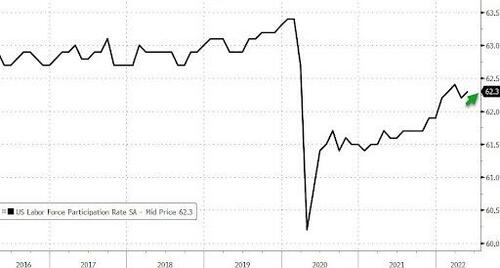

The participation rate ticked up a notch, from 62.2% to 62.3%, in line with consensus estimates.

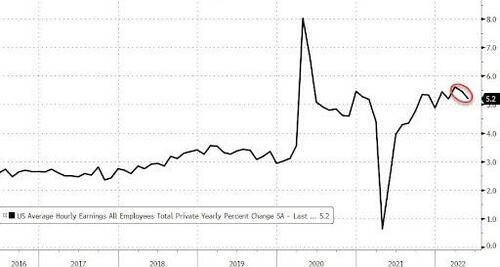

Red hot wage growth persisted, even if at an increase of 0.3% in May, and the same as last month, it missed expectations of 0.4%. Meanwhile, on an annual basis, average hourly earnings rose 5.2%, in line with expectations and down from 5.5% last month.

Average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 10 cents, or 0.3 percent, to $31.95 in May. Over the past 12 months, average hourly earnings have increased by 5.2 percent. In May, average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees rose by 15 cents, or 0.6 percent, to $27.33.

In May, the average workweek for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls was 34.6 hours for the third month in a row. In manufacturing, the average workweek for all employees was little changed at 40.4 hours, and overtime fell by 0.1 hour to 3.2 hours. The average workweek for production and nonsupervisory employees on private nonfarm payrolls remained unchanged at 34.1 hours

Reading down the report we find that the aftermath of covid will haunts the US labor market as follows:

- 7.4% of employed persons teleworked because of the coronavirus pandemic, down from 7.7% in the prior month.

- 1.8 million persons reported that they had been unable to work because their employer closed or lost business due to the pandemic--that is, they did not work at all or worked fewer hours at some point in the 4 weeks preceding the survey due to the pandemic.

- Among those who reported in May that they were unable to work because of pandemic-related closures or lost business, 19.9 percent received at least some pay from their employer for the hours not worked, also little different from the prior month.

- Among those not in the labor force in May, 455,000 persons were prevented from looking for work due to the pandemic, down from 586,000 in the prior month

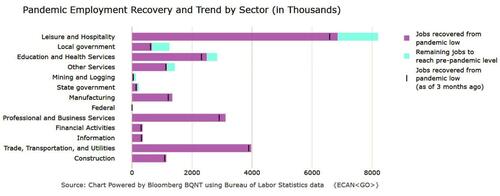

Turning to the establishment survey and a breakdown of jobs by sector, we find that notable job gains occurred in leisure and hospitality, in professional and business services, and in transportation and warehousing. Employment in retail trade declined over the month. Nonfarm employment is down by 822,000, or 0.5 percent, from its pre-pandemic level in February 2020.

Some more details:

- Employment in leisure and hospitality increased by 84,000 in May, as job growth continued in food services and drinking places (+46,000) and accommodation (+21,000). Employment in leisure and hospitality is down by 1.3 million, or 7.9 percent, compared with February 2020.

- Employment in professional and business services rose by 75,000 in May. Within the industry, job gains occurred in accounting and bookkeeping services (+16,000), computer systems design and related services (+13,000), and scientific research and development services (+6,000). Employment in professional and business services is 821,000 higher than in February 2020.

- In May, transportation and warehousing added 47,000 jobs. Employment rose in warehousing and storage (+18,000), truck transportation (+13,000), and air transportation (+6,000). Employment in transportation and warehousing is 709,000 above its February 2020 level.

- Employment in construction increased by 36,000 in May, following no change in April. In May, job gains occurred in specialty trade contractors (+17,000) and heavy and civil engineering construction (+11,000). Construction employment is 40,000 higher than in February 2020.

- In May, employment increased by 36,000 in state government education and by 33,000 in private education. Employment changed little in local government education (+14,000). Compared with February 2020, employment in state government education is up by 27,000, while employment in private education has essentially recovered. Employment in local government education is down by 308,000, or 3.8 percent, compared with February 2020.

- Employment in health care rose by 28,000 in May, including a gain in hospitals (+16,000). Employment in health care overall is 223,000, or 1.3 percent, lower than in February 2020.

- Manufacturing employment continued to trend up in May (+18,000). Job gains occurred in fabricated metal products (+7,000), wood products (+4,000), and electronic instruments (+3,000). Employment in manufacturing overall is slightly below (-17,000 or -0.1 percent) its February 2020 level.

- Wholesale trade added 14,000 jobs in May, including gains in durable goods (+10,000) and electronic markets and agents and brokers (+6,000). Employment in wholesale trade is down by 41,000, or 0.7 percent, compared with February 2020.

- Mining employment increased by 6,000 in May and is 80,000 higher than a recent low in February 2021.

- Employment in retail trade declined by 61,000 in May but is 159,000 above its February 2020 level. Over the month, job losses occurred in general merchandise stores (-33,000), clothing and clothing accessories stores (-9,000), food and beverage stores (-8,000), building material and garden supply stores (-7,000), and health and personal care stores (-5,000).

The bottom line is simple: this wasn't the collapse that so many were quietly expecting (certainly Elon Musk), and the lack of a negative shock, means that the Fed remains on a rate hiking autopilot. As Bloomberg writes, “for the Fed, this is stay-the-course data, in our view. The 50-bp hikes in June and July remain likely, while September will remain a close call for 25 bps or 50 bps. Data over the next three months will determine if the Fed decides to adjust the pace of hikes.”

Heading into today’s key payrolls print, we had a feeling that contrary to Wall Street’s generally cheerful expectations, the jobs number would be bad based on dismal real-time indicators (as described in “We Could See A Million Layoffs Or More” – Here Comes The Job Market Shock), and the latest Goldman macro data, and we… were off, because moments ago the BLS reported that in May the US added 390K jobs, which was a drop from last month’s upward revised 436K and the lowest since April 2021, but was well above the 320K expected (and once again made a mockery of the recent dismal ADP prints, which suggests that there was another political component here in the BLS data where someone likely made a phone call or two).

The change in total nonfarm payroll employment for March was revised down by 30,000, from +428,000 to +398,000, and the change for April was revised up by 8,000, from +428,000 to +436,000. With these revisions, employment in March and April combined is 22,000 lower than previously reported.

Breaking down the jobs, we see that in May, lower-paying 175K service jobs were added, down notably from 273K a month earlier, while higher-paying service jobs were unchanged at 99K; manufacturing jobs collapsed to 18K from 61K, offset by a surge in minind and logging jobs to 41K. 57K government jobs rounded out the picture.

The unemployment rate was unchanged at 3.6%, and missed expectations of a drop to 3.5%, which would have been the lowest print since the covid crisis.

Among the major worker groups, the unemployment rate for Asians declined to 2.4 percent in May. The jobless rates for adult men (3.4 percent), adult women (3.4 percent), teenagers (10.4 percent), Whites (3.2 percent), Blacks (6.2 percent), and Hispanics (4.3 percent) showed little or no change over the month.

Some more details on the composition of unemployed workers:

- Among the unemployed, the number of permanent job losers remained at 1.4 million in May. The number of persons on temporary layoff was little changed at 810,000. Both measures are little different from their values in February 2020

- The number of long-term unemployed (those jobless for 27 weeks or more) edged down to 1.4 million. This measure is 235,000 higher than in February 2020. The long-term unemployed accounted for 23.2 percent of all unemployed persons in May

- The number of persons employed part time for economic reasons increased by 295,000 to 4.3 million in May, reflecting an increase in the number of persons whose hours were cut due to slack work or business conditions. The number of persons employed part time for economic reasons is little different from its February 2020 level. These individuals, who would have preferred full-time employment, were working part time because their hours had been reduced or they were unable to find full-time jobs.

- The number of persons not in the labor force who currently want a job was little changed at 5.7 million in May. This measure remains above its February 2020 level of 5.0 million. These individuals were not counted as unemployed because they were not actively looking for work during the 4 weeks preceding the survey or were unavailable to take a job

- Among those not in the labor force who wanted a job, the number of persons marginally attached to the labor force, at 1.5 million, changed little in May. These individuals wanted and were available for work and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months but had not looked for work in the 4 weeks preceding the survey. Discouraged workers, a subset of the marginally attached who believed that no jobs were available for them, numbered 415,000 in May, also little changed from the prior month.

The participation rate ticked up a notch, from 62.2% to 62.3%, in line with consensus estimates.

Red hot wage growth persisted, even if at an increase of 0.3% in May, and the same as last month, it missed expectations of 0.4%. Meanwhile, on an annual basis, average hourly earnings rose 5.2%, in line with expectations and down from 5.5% last month.

Average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 10 cents, or 0.3 percent, to $31.95 in May. Over the past 12 months, average hourly earnings have increased by 5.2 percent. In May, average hourly earnings of private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees rose by 15 cents, or 0.6 percent, to $27.33.

In May, the average workweek for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls was 34.6 hours for the third month in a row. In manufacturing, the average workweek for all employees was little changed at 40.4 hours, and overtime fell by 0.1 hour to 3.2 hours. The average workweek for production and nonsupervisory employees on private nonfarm payrolls remained unchanged at 34.1 hours

Reading down the report we find that the aftermath of covid will haunts the US labor market as follows:

- 7.4% of employed persons teleworked because of the coronavirus pandemic, down from 7.7% in the prior month.

- 1.8 million persons reported that they had been unable to work because their employer closed or lost business due to the pandemic–that is, they did not work at all or worked fewer hours at some point in the 4 weeks preceding the survey due to the pandemic.

- Among those who reported in May that they were unable to work because of pandemic-related closures or lost business, 19.9 percent received at least some pay from their employer for the hours not worked, also little different from the prior month.

- Among those not in the labor force in May, 455,000 persons were prevented from looking for work due to the pandemic, down from 586,000 in the prior month

Turning to the establishment survey and a breakdown of jobs by sector, we find that notable job gains occurred in leisure and hospitality, in professional and business services, and in transportation and warehousing. Employment in retail trade declined over the month. Nonfarm employment is down by 822,000, or 0.5 percent, from its pre-pandemic level in February 2020.

Some more details:

- Employment in leisure and hospitality increased by 84,000 in May, as job growth continued in food services and drinking places (+46,000) and accommodation (+21,000). Employment in leisure and hospitality is down by 1.3 million, or 7.9 percent, compared with February 2020.

- Employment in professional and business services rose by 75,000 in May. Within the industry, job gains occurred in accounting and bookkeeping services (+16,000), computer systems design and related services (+13,000), and scientific research and development services (+6,000). Employment in professional and business services is 821,000 higher than in February 2020.

- In May, transportation and warehousing added 47,000 jobs. Employment rose in warehousing and storage (+18,000), truck transportation (+13,000), and air transportation (+6,000). Employment in transportation and warehousing is 709,000 above its February 2020 level.

- Employment in construction increased by 36,000 in May, following no change in April. In May, job gains occurred in specialty trade contractors (+17,000) and heavy and civil engineering construction (+11,000). Construction employment is 40,000 higher than in February 2020.

- In May, employment increased by 36,000 in state government education and by 33,000 in private education. Employment changed little in local government education (+14,000). Compared with February 2020, employment in state government education is up by 27,000, while employment in private education has essentially recovered. Employment in local government education is down by 308,000, or 3.8 percent, compared with February 2020.

- Employment in health care rose by 28,000 in May, including a gain in hospitals (+16,000). Employment in health care overall is 223,000, or 1.3 percent, lower than in February 2020.

- Manufacturing employment continued to trend up in May (+18,000). Job gains occurred in fabricated metal products (+7,000), wood products (+4,000), and electronic instruments (+3,000). Employment in manufacturing overall is slightly below (-17,000 or -0.1 percent) its February 2020 level.

- Wholesale trade added 14,000 jobs in May, including gains in durable goods (+10,000) and electronic markets and agents and brokers (+6,000). Employment in wholesale trade is down by 41,000, or 0.7 percent, compared with February 2020.

- Mining employment increased by 6,000 in May and is 80,000 higher than a recent low in February 2021.

- Employment in retail trade declined by 61,000 in May but is 159,000 above its February 2020 level. Over the month, job losses occurred in general merchandise stores (-33,000), clothing and clothing accessories stores (-9,000), food and beverage stores (-8,000), building material and garden supply stores (-7,000), and health and personal care stores (-5,000).

The bottom line is simple: this wasn’t the collapse that so many were quietly expecting (certainly Elon Musk), and the lack of a negative shock, means that the Fed remains on a rate hiking autopilot. As Bloomberg writes, “for the Fed, this is stay-the-course data, in our view. The 50-bp hikes in June and July remain likely, while September will remain a close call for 25 bps or 50 bps. Data over the next three months will determine if the Fed decides to adjust the pace of hikes.”