By Seth Carpetner, global chief economist at Morgan Stanley

Divergences in policy rates are now in focus, accentuated by the sharp depreciation of the yen and the euro. I want to turn attention to the divergent paths for central bank balance sheets.

Fed quantitative tightening (QT) started in June, and the pace will double in September. While the ECB’s balance sheet has started to shrink a bit as targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) are repaid, the contraction is small, and prepaying TLTROs is very different than QT. And the shrinking may not last as the ECB confronts peripheral spreads. The BoJ could go in the opposite direction, and yield curve control (YCC) could turn into substantial QE if markets keep testing the Bank. These balance sheet differences will only become starker.

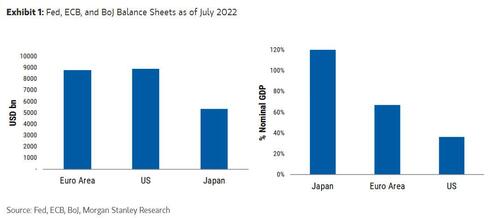

In absolute terms, the ECB and the Fed have the largest balance sheets, with the BoJ a distant third. But relative to GDP, the BoJ has the biggest by far, with the ECB second. The Fed is an outlier on the low side, and as its QT continues and accelerates, the Fed’s footprint will contract further while the BoJ’s will likely grow.

The Fed started trimming its balance sheet last month, and the pace of the unwind will accelerate in September to $60bn per month of Treasuries and $35bn per month of MBS. The Fed plans to let QT run in the background, and it seems very likely to me that balance sheet runoff keeps going even if the economy stalls (for a differing opinion from BofA's Marc Cabana, see here). Chair Powell keeps reminding us that the FOMC wants the funds rate to be tool of first recourse, so if we get to the point of the economy faltering, there will be room to cut. Indeed, that narrative is priced into the futures curve already.

For the ECB, the balance sheet trajectory is complicated. QT and TLTRO prepayments are not the same. Running off securities gives the market no choice—the central bank calls the shots. With TLTROs, commercial banks have the option to prepay at their discretion. Indeed, as our Europe team has noted, prepayments have been on the low side of expectations. Proper QT for the ECB is far off. Moreover, the ECB’s vow to contain peripheral spreads with a yet-to-be defined “anti-fragmentation tool” points to a potentially significant upside risk to the size of its balance sheet.

The BoJ is at the other end of the spectrum. Relative to GDP (and even more so, relative to the size of the sovereign debt market), the BoJ’s balance sheet is already an outlier to the upside. And despite the fall in the yen, inflation is still lower in Japan than other DMs, leaving Governor Kuroda committed to his very accommodative policy stance. That mindset will confront slower global growth that weighs on Japanese growth. Against this backdrop, our Japan team revised the call for the timing of a shift in YCC. Whereas we had thought that a tweak would come in October, allowing the JGB curve to drift upward, we now expect YCC to be maintained until the second quarter of next year, after Governor Kuroda is replaced by a successor. With the market increasingly likely to test the BoJ, I see the risks to the balance sheet as skewed substantially to the upside.

Markets have a lot to digest. Following the Covid shock, all major central banks were moving in the same direction but no longer, and market liquidity will be buffeted by severe crosscurrents. The irony is that the risks come from both larger and smaller balance sheets. In dollar markets, a lot more Treasuries and MBS will have to be absorbed as financing costs are rising. In JGBs, the BoJ already owns half the market, and more might be coming.

By Seth Carpetner, global chief economist at Morgan Stanley

Divergences in policy rates are now in focus, accentuated by the sharp depreciation of the yen and the euro. I want to turn attention to the divergent paths for central bank balance sheets.

Fed quantitative tightening (QT) started in June, and the pace will double in September. While the ECB’s balance sheet has started to shrink a bit as targeted long-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) are repaid, the contraction is small, and prepaying TLTROs is very different than QT. And the shrinking may not last as the ECB confronts peripheral spreads. The BoJ could go in the opposite direction, and yield curve control (YCC) could turn into substantial QE if markets keep testing the Bank. These balance sheet differences will only become starker.

In absolute terms, the ECB and the Fed have the largest balance sheets, with the BoJ a distant third. But relative to GDP, the BoJ has the biggest by far, with the ECB second. The Fed is an outlier on the low side, and as its QT continues and accelerates, the Fed’s footprint will contract further while the BoJ’s will likely grow.

The Fed started trimming its balance sheet last month, and the pace of the unwind will accelerate in September to $60bn per month of Treasuries and $35bn per month of MBS. The Fed plans to let QT run in the background, and it seems very likely to me that balance sheet runoff keeps going even if the economy stalls (for a differing opinion from BofA’s Marc Cabana, see here). Chair Powell keeps reminding us that the FOMC wants the funds rate to be tool of first recourse, so if we get to the point of the economy faltering, there will be room to cut. Indeed, that narrative is priced into the futures curve already.

For the ECB, the balance sheet trajectory is complicated. QT and TLTRO prepayments are not the same. Running off securities gives the market no choice—the central bank calls the shots. With TLTROs, commercial banks have the option to prepay at their discretion. Indeed, as our Europe team has noted, prepayments have been on the low side of expectations. Proper QT for the ECB is far off. Moreover, the ECB’s vow to contain peripheral spreads with a yet-to-be defined “anti-fragmentation tool” points to a potentially significant upside risk to the size of its balance sheet.

The BoJ is at the other end of the spectrum. Relative to GDP (and even more so, relative to the size of the sovereign debt market), the BoJ’s balance sheet is already an outlier to the upside. And despite the fall in the yen, inflation is still lower in Japan than other DMs, leaving Governor Kuroda committed to his very accommodative policy stance. That mindset will confront slower global growth that weighs on Japanese growth. Against this backdrop, our Japan team revised the call for the timing of a shift in YCC. Whereas we had thought that a tweak would come in October, allowing the JGB curve to drift upward, we now expect YCC to be maintained until the second quarter of next year, after Governor Kuroda is replaced by a successor. With the market increasingly likely to test the BoJ, I see the risks to the balance sheet as skewed substantially to the upside.

Markets have a lot to digest. Following the Covid shock, all major central banks were moving in the same direction but no longer, and market liquidity will be buffeted by severe crosscurrents. The irony is that the risks come from both larger and smaller balance sheets. In dollar markets, a lot more Treasuries and MBS will have to be absorbed as financing costs are rising. In JGBs, the BoJ already owns half the market, and more might be coming.