By Seth Carpenter, Morgan Stanley Global Chief Economist

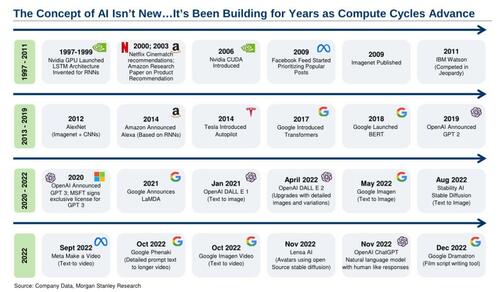

The topic of artificial intelligence (AI) is still top of mind in markets, in particular among equity investors, who have to sort the winners from the losers and decide how to trade the theme. The macro topics of employment, inflation, and interest rates are relevant to the theme as well. Over time, we will learn how AI gets deployed, in which industries, and over what time horizon the benefits are realized.

For employment, I continue to be skeptical of the gloomy prognostications that a myriad of workers will lose their jobs to new technology. Economies evolve, and the advent of the lightbulb has not left a lingering horde of unemployed candlemakers. The implications for labor markets can be categorized (following, for example, Acemoglu (2021)) into a productivity effect, a displacement effect, and a reinstatement effect. Higher productivity makes each worker more profitable and thus should increase the demand for labor over time. But some will be displaced in the short run, as fewer workers are needed and tasks get automated. But a frequently overlooked factor is that new technology creates new jobs, reinstating many workers. The invention of the computer created a need for computer programmers. Because displacement can be more of a short-run phenomenon, the faster the adoption of the new technology, the higher the risks of an adverse effect on employment. The timing of adoption and deployment is still unclear;my colleague Joe Moore and his team have highlighted immediate market effects, while our recent CIO survey suggests that firms are looking into AI, but that an immediate disruption is not likely.

We should also remember that simply because the same work can be done by fewer workers, the result is not lower employment. History suggests we will simply see more output. The legal profession is often cited as ripe for disruption by AI. But the question remains whether the same amount of legal work will be done with fewer paralegals and associates, or instead, if items such as wills and trusts will go from being the purview of the relatively wealthy to becoming ubiquitous. Confoundingly, the higher output may not be measurable. In financial services, for example, AI is being explored and deployed. Institutional investors may learn to cover more single-name stocks than ever before and develop investment theses across more and more asset classes. Doing more work without reducing employment is clearly a plausible outcome, but if the whole industry adopts the technology, gains will be competed away. The result may be no measured efficiency gains or an arms race with no winner.

But surely, across the various applications, there will be some net increase in meaningful and measurable productivity, allowing the economy to produce more at lower cost. The result eventually would be a disinflationary impulse. For now, the Fed is working on bringing inflation down through restrictive monetary policy—AI or not. And since the productivity gains will only play out over time, we can think about the period after the Fed has restored price stability. Will inflation fall back below target? Only until the Fed sees the disinflation happening, and then it will want to ease policy to take up the slack created by a more-productive economy.

While the disinflation from rising productivity should first lead to lower policy rates, over time, if productivity gains are large and sustained, we should actually see higher policy rates. The greater productivity is, the greater the incentive to invest. To keep the economy in equilibrium with rising productivity takes higher interest rates. And if the higher productivity growth is expected to last for some time, the higher rates should be reflected across the entire yield curve. Further, because the higher rates would be driven by fundamentals and not inflation, the entire real yield curve should rise. But, instead of seeing higher real rates as a negative for equities, faster productivity growth means that both earnings and real rates can rise in tandem—a shift in a correlation that many in markets have become used to.

By Seth Carpenter, Morgan Stanley Global Chief Economist

The topic of artificial intelligence (AI) is still top of mind in markets, in particular among equity investors, who have to sort the winners from the losers and decide how to trade the theme. The macro topics of employment, inflation, and interest rates are relevant to the theme as well. Over time, we will learn how AI gets deployed, in which industries, and over what time horizon the benefits are realized.

For employment, I continue to be skeptical of the gloomy prognostications that a myriad of workers will lose their jobs to new technology. Economies evolve, and the advent of the lightbulb has not left a lingering horde of unemployed candlemakers. The implications for labor markets can be categorized (following, for example, Acemoglu (2021)) into a productivity effect, a displacement effect, and a reinstatement effect. Higher productivity makes each worker more profitable and thus should increase the demand for labor over time. But some will be displaced in the short run, as fewer workers are needed and tasks get automated. But a frequently overlooked factor is that new technology creates new jobs, reinstating many workers. The invention of the computer created a need for computer programmers. Because displacement can be more of a short-run phenomenon, the faster the adoption of the new technology, the higher the risks of an adverse effect on employment. The timing of adoption and deployment is still unclear;my colleague Joe Moore and his team have highlighted immediate market effects, while our recent CIO survey suggests that firms are looking into AI, but that an immediate disruption is not likely.

We should also remember that simply because the same work can be done by fewer workers, the result is not lower employment. History suggests we will simply see more output. The legal profession is often cited as ripe for disruption by AI. But the question remains whether the same amount of legal work will be done with fewer paralegals and associates, or instead, if items such as wills and trusts will go from being the purview of the relatively wealthy to becoming ubiquitous. Confoundingly, the higher output may not be measurable. In financial services, for example, AI is being explored and deployed. Institutional investors may learn to cover more single-name stocks than ever before and develop investment theses across more and more asset classes. Doing more work without reducing employment is clearly a plausible outcome, but if the whole industry adopts the technology, gains will be competed away. The result may be no measured efficiency gains or an arms race with no winner.

But surely, across the various applications, there will be some net increase in meaningful and measurable productivity, allowing the economy to produce more at lower cost. The result eventually would be a disinflationary impulse. For now, the Fed is working on bringing inflation down through restrictive monetary policy—AI or not. And since the productivity gains will only play out over time, we can think about the period after the Fed has restored price stability. Will inflation fall back below target? Only until the Fed sees the disinflation happening, and then it will want to ease policy to take up the slack created by a more-productive economy.

While the disinflation from rising productivity should first lead to lower policy rates, over time, if productivity gains are large and sustained, we should actually see higher policy rates. The greater productivity is, the greater the incentive to invest. To keep the economy in equilibrium with rising productivity takes higher interest rates. And if the higher productivity growth is expected to last for some time, the higher rates should be reflected across the entire yield curve. Further, because the higher rates would be driven by fundamentals and not inflation, the entire real yield curve should rise. But, instead of seeing higher real rates as a negative for equities, faster productivity growth means that both earnings and real rates can rise in tandem—a shift in a correlation that many in markets have become used to.

Loading…