By Andrew Sheets, Chief Cross-Asset Strategist for Morgan Stanley, as excerpted from the bank's Sunday Start.

At the west end of the new rail station in Canary Wharf, up the escalators and to the right, is a coffee shop. It’s full of wooden panelling and a big chalkboard above the tills with the price of the drinks. Faint markings on the chalkboard make something very clear. The prices have been changing.

The United Kingdom is the world’s sixth-largest economy and faces a complicated, interwoven set of challenges. It is a volatile and fascinating cross-asset story.

First among these challenges is inflation. High UK inflation is partly due to global factors like commodity prices, but even excluding food and energy core inflation in the UK is 6.3%Y. Since the UK runs a large current account deficit (5.5% of GDP), a weak currency is driving higher costs on imported items. Meanwhile, Brexit has reduced the supply of labor and increased the costs of trade, boosting inflation and reducing the benefit that a weaker currency would otherwise bring.

The circularity here is unmissable; high inflation drives currency weakness, and vice versa. High inflation has depressed UK real rates, making the currency less attractive to hold. And high inflation relative to other countries undermines valuations: on an inflation-adjusted basis (i.e., purchasing power parity) the British pound has ‘cheapened’ by a similar percentage as the Swiss franc over the last year, and much less than, say, the Norwegian krone. That’s hardly irrational.

If inflation is high, why doesn’t the Bank of England simply raise rates to slow demand? The BoE is moving, but as our UK economist Bruna Skarica notes, it has raised rates by less than the market expected in six of its last eight meetings. That’s left investors anticipating ~320bp of BoE hikes between now and May 2023, ~140bp more than expected from the Federal Reserve over the same period; if the UK underdelivers and the Fed does not, it could drive more FX weakness.

The BoE’s hesitation is understandable; my colleague Vasundhara Goel notes that most UK mortgage debt is only fixed for 2-5 years, with roughly 100k loans resetting every month (see "UK Mortgage Repayments Poised To Soar To Financial Crisis Levels"). The impact of higher rates can therefore flow through to the economy quickly, especially as UK households are also facing an unusually large year-on-year increase to utility costs.

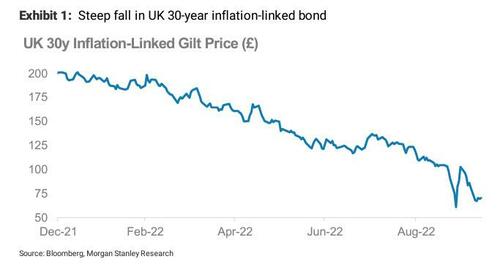

Another path to slow inflation would be tighter fiscal policy. But the UK government announced a budget to loosen fiscal policy, which was followed by further increases to UK rates and more currency weakness, which in turn put historical pressure on the country’s pension sector and contributed to UK 30-year inflation-linked bonds falling 67% from last December. To give it some context, the S&P 500 is down about 25% year to date. If the S&P 500 fell 25% three more times…it would be down about much as that 30-year UK inflation-linked bond.

Then on Friday, the government announced that the Chancellor of the Exchequer was stepping down and recent plans to cut corporate taxes would be shelved in an attempt to reassure markets. But questions remain; the UK Prime Minister stated that she still desires a "low tax" economy, and fiscal policy will still be loosened under the government's proposals. Immediately following the press conference Friday afternoon announcing these changes, GBP fell and yields rose.

The UK's problems are not insurmountable. But for the moment, they remain daunting. My colleague Wanting Low in FX strategy expects GBP to weaken to parity with USD. My colleague Theo Chapsalis, our UK rates strategist, likes being long UK 5-year inflation (RPI) and is negative on duration, expecting gilts to underperform swaps as issuance increases and the balance sheet becomes more valuable. Sterling IG credit, at a ~7.0% yield, is increasingly competitive versus UK equities, but it is also a much smaller credit market than its global peers.

A weak GBP may help UK stocks outperform EU equities, but with my colleague Graham Secker well below consensus for EPS in the region, that’s a low bar. For investors looking for deep value, we believe that the better opportunity is in emerging market equities, which we’ve just upgraded to overweight after a long period of skepticism. That upgrade is a function of both a top-down view that EM can bottom before DM markets (it has repeatedly in the past), and bottom-up work by our sector teams. Within EM, our strategists like Korea, Taiwan and Brazil.

The UK is an evolving story and essential macro viewing, but for now, we see better opportunities elsewhere.

By Andrew Sheets, Chief Cross-Asset Strategist for Morgan Stanley, as excerpted from the bank’s Sunday Start.

At the west end of the new rail station in Canary Wharf, up the escalators and to the right, is a coffee shop. It’s full of wooden panelling and a big chalkboard above the tills with the price of the drinks. Faint markings on the chalkboard make something very clear. The prices have been changing.

The United Kingdom is the world’s sixth-largest economy and faces a complicated, interwoven set of challenges. It is a volatile and fascinating cross-asset story.

First among these challenges is inflation. High UK inflation is partly due to global factors like commodity prices, but even excluding food and energy core inflation in the UK is 6.3%Y. Since the UK runs a large current account deficit (5.5% of GDP), a weak currency is driving higher costs on imported items. Meanwhile, Brexit has reduced the supply of labor and increased the costs of trade, boosting inflation and reducing the benefit that a weaker currency would otherwise bring.

The circularity here is unmissable; high inflation drives currency weakness, and vice versa. High inflation has depressed UK real rates, making the currency less attractive to hold. And high inflation relative to other countries undermines valuations: on an inflation-adjusted basis (i.e., purchasing power parity) the British pound has ‘cheapened’ by a similar percentage as the Swiss franc over the last year, and much less than, say, the Norwegian krone. That’s hardly irrational.

If inflation is high, why doesn’t the Bank of England simply raise rates to slow demand? The BoE is moving, but as our UK economist Bruna Skarica notes, it has raised rates by less than the market expected in six of its last eight meetings. That’s left investors anticipating ~320bp of BoE hikes between now and May 2023, ~140bp more than expected from the Federal Reserve over the same period; if the UK underdelivers and the Fed does not, it could drive more FX weakness.

The BoE’s hesitation is understandable; my colleague Vasundhara Goel notes that most UK mortgage debt is only fixed for 2-5 years, with roughly 100k loans resetting every month (see “UK Mortgage Repayments Poised To Soar To Financial Crisis Levels“). The impact of higher rates can therefore flow through to the economy quickly, especially as UK households are also facing an unusually large year-on-year increase to utility costs.

Another path to slow inflation would be tighter fiscal policy. But the UK government announced a budget to loosen fiscal policy, which was followed by further increases to UK rates and more currency weakness, which in turn put historical pressure on the country’s pension sector and contributed to UK 30-year inflation-linked bonds falling 67% from last December. To give it some context, the S&P 500 is down about 25% year to date. If the S&P 500 fell 25% three more times…it would be down about much as that 30-year UK inflation-linked bond.

Then on Friday, the government announced that the Chancellor of the Exchequer was stepping down and recent plans to cut corporate taxes would be shelved in an attempt to reassure markets. But questions remain; the UK Prime Minister stated that she still desires a “low tax” economy, and fiscal policy will still be loosened under the government’s proposals. Immediately following the press conference Friday afternoon announcing these changes, GBP fell and yields rose.

The UK’s problems are not insurmountable. But for the moment, they remain daunting. My colleague Wanting Low in FX strategy expects GBP to weaken to parity with USD. My colleague Theo Chapsalis, our UK rates strategist, likes being long UK 5-year inflation (RPI) and is negative on duration, expecting gilts to underperform swaps as issuance increases and the balance sheet becomes more valuable. Sterling IG credit, at a ~7.0% yield, is increasingly competitive versus UK equities, but it is also a much smaller credit market than its global peers.

A weak GBP may help UK stocks outperform EU equities, but with my colleague Graham Secker well below consensus for EPS in the region, that’s a low bar. For investors looking for deep value, we believe that the better opportunity is in emerging market equities, which we’ve just upgraded to overweight after a long period of skepticism. That upgrade is a function of both a top-down view that EM can bottom before DM markets (it has repeatedly in the past), and bottom-up work by our sector teams. Within EM, our strategists like Korea, Taiwan and Brazil.

The UK is an evolving story and essential macro viewing, but for now, we see better opportunities elsewhere.