By Vishwanath Tirupattur, Betsy L. Graseck, Morgan Stanley strategist, as excepted from Sunday Start

After 2Q bank earnings, we wrote about the regulatory capital challenges facing US banks (particularly the large caps) and the implications for risk markets, especially fixed income. Using insights from Betsy Graseck, our banks and consumer finance equity analyst, we noted that banks would need to keep dividends flat, eliminate buybacks, and reduce risk-weighted assets (RWAs) to generate a capital ratio above their required minimums, while making tough choices in their lending books. For the three largest banks (JPMorgan Chase & Co, Bank of America, and Citigroup), it meant lowering their RWAs by more than US$150 billion in aggregate by year end to maintain a 100bp management buffer on top of their regulatory capital minimums. We expected different reactions to RWA pressures across the banks, but in aggregate we looked for lower credit formation, reduced market liquidity and continued pressure on spreads for capital-intensive assets.

After banks reported 3Q earnings this week, we take a fresh look at bank capital, the banks’ strategies to address these challenges, and their effect on fixed income markets. The good news is that the three largest banks have made notable progress on the RWA front, reducing their RWAs by about $90 billion. With these reductions and other factors such as strong net income, Bank of America has met its RWA reduction needs, JPMorgan Chase & Co and Citigroup have completed two-thirds and one-third, respectively, to maintain a 100bp capital buffer. While JPM management has suggested that it might only run with a 50bp buffer, we view that as thin and see it easily increasing to historical 100bp levels if macroeconomic and FX volatility persist.

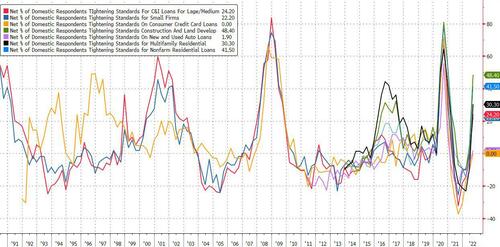

The progress in RWA reduction is not without costs. The Federal Reserve’s H.8 data show a notable deceleration in loan growth across banks in aggregate – the Q/Q change fell from US$454 billion in 2Q to $240 billion in 3Q. The deceleration at the largest three banks was notably greater, and their share of the overall loan market – auto, credit card, HELOC, CRE, residential mortgage and C&I loans combined – dropped, mainly as a result of RWA reductions. In the most recent Senior Loan Officer survey, every question on lending conditions flipped to tightening, further evidence of how US banks are approaching their lending books.

What about market liquidity in secondary markets?

Amid the forced selling dynamic in US corporate credit on the back of the volatility in the UK markets, the issue has received much attention. Condensing liquidity to a single measure is hard. Bid-offer spreads in credit are one measure of liquidity. Even though secondary markets in corporate credit have been largely well behaved, bid-offer spreads for credit have widened from the lows of 2021, suggesting deteriorating market liquidity. In our view, RWA pressures on dealer balance sheets have contributed to this widening.

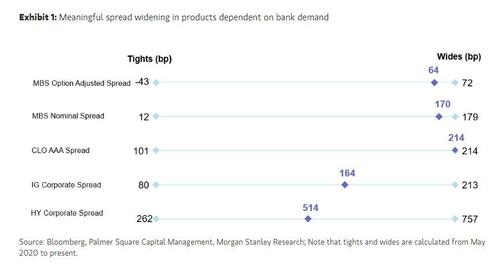

The deterioration of market liquidity is by no means limited to corporate credit markets. The effects of RWA reduction are more pronounced in securitized product markets, with banks reducing their footprint in trading and their portfolio assets with higher RWAs. Banks have traditionally been major buyers in their portfolios of conventional agency MBS and AAA tranches of securitized products such as CLOs, both of which carry a 20% risk weight. Agency MBS, which are backed by the US government, have virtually no credit risk. Senior tranches of securitized products like CLOs are structured to be credit-risk remote and their structural resilience has been tested over multiple default cycles. Banks are not big buyers of corporate bonds.

Comparing the moves in corporate credit spreads with agency MBS and CLO AAAs illustrates their relative dependency on bank buying. As shown in Exhibit 1, spreads on agency MBS and CLO AAAs currently sit at or near the wides of their post-Covid ranges, while corporate credit spreads are around the middle of the range. Spreads have widened meaningfully in products that need bank sponsorship – in our view, a direct consequence of RWA reductions.

What does this mean for investors? First, there is more wood to chop on the RWA front, which means the deceleration in loan growth will likely continue in 4Q. Second, market turbulence (e.g., the recent volatility in UK markets) in one market could magnify the moves in other markets. Thus, low liquidity will likely remain a headwind to the smooth functioning of markets. Third, the incrementally greater widening in certain spread products thanks to bank buyers stepping away could create an opportunity for investors that do not face the same capital pressures. The fundamentals of these instruments have not changed but market valuations are cheaper for reasons that are not grounded in fundamentals.

By Vishwanath Tirupattur, Betsy L. Graseck, Morgan Stanley strategist, as excepted from Sunday Start

After 2Q bank earnings, we wrote about the regulatory capital challenges facing US banks (particularly the large caps) and the implications for risk markets, especially fixed income. Using insights from Betsy Graseck, our banks and consumer finance equity analyst, we noted that banks would need to keep dividends flat, eliminate buybacks, and reduce risk-weighted assets (RWAs) to generate a capital ratio above their required minimums, while making tough choices in their lending books. For the three largest banks (JPMorgan Chase & Co, Bank of America, and Citigroup), it meant lowering their RWAs by more than US$150 billion in aggregate by year end to maintain a 100bp management buffer on top of their regulatory capital minimums. We expected different reactions to RWA pressures across the banks, but in aggregate we looked for lower credit formation, reduced market liquidity and continued pressure on spreads for capital-intensive assets.

After banks reported 3Q earnings this week, we take a fresh look at bank capital, the banks’ strategies to address these challenges, and their effect on fixed income markets. The good news is that the three largest banks have made notable progress on the RWA front, reducing their RWAs by about $90 billion. With these reductions and other factors such as strong net income, Bank of America has met its RWA reduction needs, JPMorgan Chase & Co and Citigroup have completed two-thirds and one-third, respectively, to maintain a 100bp capital buffer. While JPM management has suggested that it might only run with a 50bp buffer, we view that as thin and see it easily increasing to historical 100bp levels if macroeconomic and FX volatility persist.

The progress in RWA reduction is not without costs. The Federal Reserve’s H.8 data show a notable deceleration in loan growth across banks in aggregate – the Q/Q change fell from US$454 billion in 2Q to $240 billion in 3Q. The deceleration at the largest three banks was notably greater, and their share of the overall loan market – auto, credit card, HELOC, CRE, residential mortgage and C&I loans combined – dropped, mainly as a result of RWA reductions. In the most recent Senior Loan Officer survey, every question on lending conditions flipped to tightening, further evidence of how US banks are approaching their lending books.

What about market liquidity in secondary markets?

Amid the forced selling dynamic in US corporate credit on the back of the volatility in the UK markets, the issue has received much attention. Condensing liquidity to a single measure is hard. Bid-offer spreads in credit are one measure of liquidity. Even though secondary markets in corporate credit have been largely well behaved, bid-offer spreads for credit have widened from the lows of 2021, suggesting deteriorating market liquidity. In our view, RWA pressures on dealer balance sheets have contributed to this widening.

The deterioration of market liquidity is by no means limited to corporate credit markets. The effects of RWA reduction are more pronounced in securitized product markets, with banks reducing their footprint in trading and their portfolio assets with higher RWAs. Banks have traditionally been major buyers in their portfolios of conventional agency MBS and AAA tranches of securitized products such as CLOs, both of which carry a 20% risk weight. Agency MBS, which are backed by the US government, have virtually no credit risk. Senior tranches of securitized products like CLOs are structured to be credit-risk remote and their structural resilience has been tested over multiple default cycles. Banks are not big buyers of corporate bonds.

Comparing the moves in corporate credit spreads with agency MBS and CLO AAAs illustrates their relative dependency on bank buying. As shown in Exhibit 1, spreads on agency MBS and CLO AAAs currently sit at or near the wides of their post-Covid ranges, while corporate credit spreads are around the middle of the range. Spreads have widened meaningfully in products that need bank sponsorship – in our view, a direct consequence of RWA reductions.

What does this mean for investors? First, there is more wood to chop on the RWA front, which means the deceleration in loan growth will likely continue in 4Q. Second, market turbulence (e.g., the recent volatility in UK markets) in one market could magnify the moves in other markets. Thus, low liquidity will likely remain a headwind to the smooth functioning of markets. Third, the incrementally greater widening in certain spread products thanks to bank buyers stepping away could create an opportunity for investors that do not face the same capital pressures. The fundamentals of these instruments have not changed but market valuations are cheaper for reasons that are not grounded in fundamentals.