Public domain

Wherever one looks, socialism leaves behind a legacy of suffering and death on a mass scale, and Bangladesh's socialist experiment was no exception.In 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman led his country, Bangladesh, to independence from Pakistan. Afterward, he ruled as a brutal tyrant, turned to communist economics, and starved to death over one million people. Then he was assassinated.

However, his surviving daughter, Sheikh Hasina, later rose to power in Bangladesh, establishing a cronyist, leftist dictatorship. Her regime never reinstated her father’s communist economic policies, but it did create a personality cult of Mujibur Rahman, commonly known in the region simply as Mujib.

Mujib was proclaimed the ‘greatest Bengali in a 1000 years.’ His daughter’s regime dedicated a whole month of each year to “mourning” Mujibur Rahman’s assassination.

Sheikh Hasina herself was overthrown recently amidst outrage over her regime’s brutal repression of student demonstrators. Urban liberals, conservative nationalists, and radical Islamists united behind the protest movement, forcing Bangladesh’s armed forces to depose Hasina.

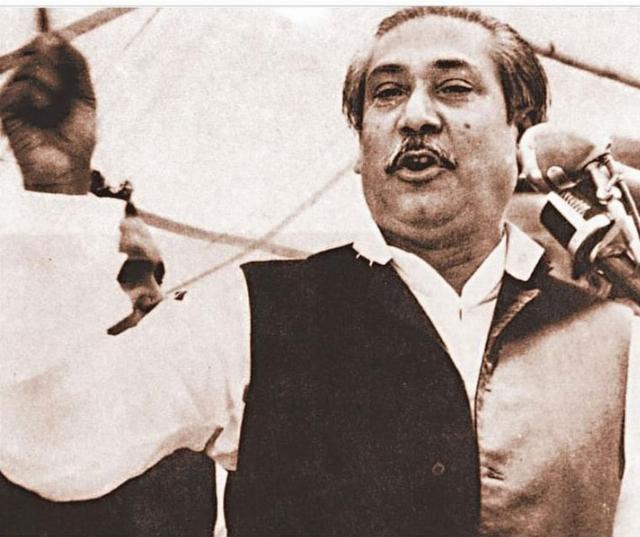

<img alt captext="Public domain” src=”https://conservativenewsbriefing.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/mujibur-rahman-a-forgotten-socialist-mass-murderer-of-the-20th-century.jpg” width=”550″>

Image: Mujibur Rahman. Public domain.

As Bangladeshis take their country back from decades of leftwing misrule and historical falsification, it is now more important than ever to tell the forbidden truth about Mujibur Rahman, for he was the worst communist-inspired mass murderer in the history of the Indian subcontinent.

Mujib started his career as a pragmatic, populist politician during the British Raj when the colonial authorities first arrested him. After the Indian subcontinent was partitioned in 1947, Bangladesh found itself awkwardly lumped together with a linguistically and culturally alien Pakistan in a single Muslim-majority state.

Mujib wasn’t known for any interest in communism; he demanded linguistic and political rights for Bangladeshis. For this, various military regimes that came to rule Pakistan jailed him. The famous British-Pakistani investigative journalist Anthony Mascarenhas, Mujib’s friend for many years, suggested that Mujib’s prison experience had fundamentally changed him. “Total isolation in prison had been an obliterating experience.”

In early 1971, the Pakistani army launched a campaign of systematic sexual violence, genocide, and burnt-earth tactics in a last-ditch attempt to repress insurgents fighting for Bangladeshi freedom. Marcerenhas, in his acclaimed (and out-of-print) book, Bangladesh: A Legacy of Blood, described this campaign of atrocities as “the Rape of Bangladesh.”*

Despite extensive assistance from local Islamist collaborators, the Pakistani army in Bangladesh surrendered unconditionally in December 1971. Mujib was suddenly released from Pakistani jail, and in January 1972, in a hotel room in London, was told that he would be returning to Bangladesh as the head of state of an independent country.

Upon his return, Mujib had a unique chance to rebuild his devastated homeland in his image. His Awami League (People’s League) party had an unchallengeable position from which to lead the newly independent nation, for it had the sort of popular mandate only war victory could give. Yet, within less than three years, as Mascarenhas reported, Bangladeshis were on the streets shouting that “the Awami Leaguers are more corrupt and much worse than the Pakistanis ever were.”

What went wrong? In a word, communism.

Instead of using tried and tested capitalist strategies for wealth creation, Mujib turned to communist-inspired economic thinking and dictatorial misrule. Socialism is known to have failed in every place on earth where it was ever tried, and and quickly did so in Bangladesh, too.

The Bangladeshi economist Dilruba Begum noted that Mujib’s economic policies were rooted in “industrial socialism, government rationing, restriction of private investment, control of foreign exchange, and discouragement of foreign investment.” By March 1972, just two months after his return to Bangladesh, Mujib’s government had begun ‘nationalizing’ (i.e., expropriating) heavy industry.

Socialist suppression of free markets had predictable consequences. Mascarenhas reported that “one of Mujib’s senior officers was so adept at manipulating the food market that he arranged, first a shortage of salt, and then a famine of chillies before flooding the market with imports of these items brought in by his own cargo vessels. Others manipulated the rice trade, the edible oils market.” Inflation exploded, and people struggled to afford everyday essentials.

By 1973, Mujib was posing for photos with Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. In the years before, Castro had turned his country from one of the wealthiest in the Caribbean into a pitiful communist open-air prison. According to Bangladeshi sources, Castro was enthralled with his new friend Mujib. Castro reportedly said, “I have not seen the Himalayas. But I have seen Sheikh Mujib. In personality and in courage, this man is the Himalayas.”

At the time, it was US policy not to offer taxpayer-funded food aid to countries that maintained trade relations with communist Cuba. Similarly, the Soviet Union did not offer aid to developing countries aligned with the West. In 1974, forced to choose between an “agreement signed with Cuba to sell 4 million jute bags (worth less than $5 Million)” and continuing to receive extensive US food aid, Mujib initially preferred to maintain these minor trade relations with Cuba, dragging his feet for months. The US predictably cut off food aid. Whenever international food aid arrived, corrupt officials in Mujib’s government immediately exported it to markets in India in exchange for hard currency.

Research has found that, by 1974, the Mujib regime’s foreign exchange reserves were lower than “outstanding claims on bills for imports.” This “essentially meant the country went bankrupt,” leading to now-unaffordable commercial food shipments being canceled. According to Mascarenhas’s reporting, this acute lack of money for food didn’t stop Mujib from paying a special “£6000 training fee” to Sandhurst Military Academy in Britain to admit his underqualified son Yamal. Previously, Yamal left the communist Yugoslav Military Academy as he “couldn’t cope” with studies there.

Also, in 1974, a devastating famine broke out in Bangladesh. Thanks to Mujib’s economic policies, up to one million ordinary Bangladeshis are estimated to have starved or have died from malnutrition-related diseases.

The Nobel-prize-winning economist Amartya Sen, hardly a right-winger, noted that “food was being exported from the famine-stricken country” while the famine was ongoing. She termed the famine not a failure of food availability but of food distribution. Dilruba Begum concurred in her analysis, describing the famine as “a failure of allocation, resulting from government interference with private exchange… [T]he Mujib government had widely substituted political control for market allocation.”

Mujib responded not by moving away from ruinous socialist policies but by doubling down on them. By December 1974, he announced a state of emergency that suspended all civil rights, even those that previously existed on paper only.

As millions of hungry people flooded the capital, Mujib activated his notorious paramilitary organization, the Rakkhi Bahini. Mujib had earlier used the Rakkhi Bahini to extrajudicially kill his opponents, including some Marxists who were idealistically opposed to his rule.

According to Mascarenhas’s reporting, the Rakkhi Bahini were now charged with rounding up some of the starving, impoverished people on the capital’s streets and putting them in detention camps behind barbed wire. There were “no medical supplies, no means of income” in these enclosed camps, Mascarenhas notes.

With the poor locked up behind barbed wire, Mujib moved to formally give up the pretense that his Bangladesh was a parliamentary democracy. In February 1975, he proclaimed what one scholar, Taj Hashimi, called a “Soviet-style one party dictatorship” led by a single leftwing party called the BAKSAL. Under the one-party regime, Mujib rushed to propose “collectivization of agriculture à la Soviet Union,” Hashimi noted.

Given the Soviet experience with collectivism, it seems likely that, if implemented, Mujib’s similar ideas could easily have starved millions more. But this never came to pass. Mujib, it turned out, had made one mistake too many.

As Mascarenhas reported, Mujib had personally released from prison an Awami League official who had murdered a newly-wed couple and their taxi driver, raping and mutilating the bride before killing her. This shameless grant of impunity to a sadistic killer angered a young Bangladeshi army officer, Major Farook, so deeply that he and his colleagues swore to kill Mujib.

“Here was the head of government abetting murder and other extreme things from which he was supposed to protect us. This was not acceptable. We decided he must go,” Mascarenhas quoted him as saying.

On August 15, 1975, Major Farook and other disgruntled army officers shot dead Mujib and many other members of his family in an early-morning raid on his residence. It was a blood-soaked ending for a blood-soaked regime.

_____________________

*All quotations attributed to Mascasrenhas come from Bangladesh: A Legacy of Blood.