Monday's furious rally, which among other things was facilitated by the Sunday report from WSJ Fed mouthpiece Nick Timiraos that a 25bps Feb 1 rate hike by the Fed is a done deal, hit an airpocket just after 2pm when in the latest tweet from Timiraos - whose every utterance now moves markets, especially during the Fed blackout period - and in which the WSJ reporter noted that "Just when signs point to easing inflation worldwide, China’s economic reopening after years of strict pandemic controls is raising questions about whether it could spur costs higher again."

Just when signs point to easing inflation worldwide, China’s economic reopening after years of strict pandemic controls is raising questions about whether it could spur costs higher again https://t.co/NA8Wr3l2L3

— Nick Timiraos (@NickTimiraos) January 23, 2023

Needless to say, China's economic reopening is a very sensitive issue: on one hand, there are those who argue easier access to reopened Chinese markets will mean smoother supply chains and cheaper goods (and transit) contributing to the current disinflation; on the other hand, should China's reopening turn out to be "hot" and should Beijing end up exporting too much inflation (as it has in the past), it could reverse any "pause" or "pivot" plans the Fed has, and instead force it to double down on tightening later in 2023.

Yes, and this is similar to what Powell said when asked about reopening effects last month. The two offset each other to some effect, but the exact net effect is very uncertain. https://t.co/yHWtXwz4fV pic.twitter.com/GZdBlVCjna

— Nick Timiraos (@NickTimiraos) January 23, 2023

While we will have much more to say on this topic in the coming days, the initial consensus on Wall Street is that a Chinese reopening will not, in fact, be inflationary. Take last week's Cross-Asset Dispatches note from Morgan Stanley, in which strategist Andrew Sheets explains why expectations that China's reopening will be inflationary will disappoint. We excerpt from his note below:

We don't think that China's reopening will be inflationary

Wage growth is one risk to the Morgan Stanley 'inflation falls' thesis. Another is China's reopening from Covid-zero, which has been increasingly aggressive. Our forecasts imply that this reopening will be successful, with our economists optimistic on China growth, and our strategists optimistic on China equities and FX.

But if the world's second-largest economy successfully reopens from Covid, won't that drive more inflationary pressure in 2023?

Not necessarily. Our economists see a few considerations:

- Private consumption sees the largest rebound: Private consumption in China saw the largest drop-off as a result of Covid-zero, and has the most to gain from this ending, especially with high private savings. This demand competes less at the international level than more commodity-heavy public investment.

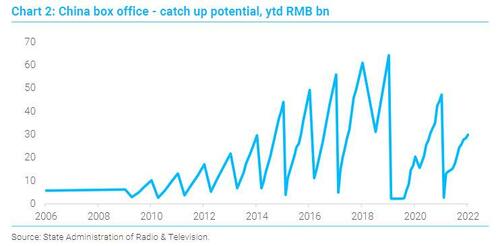

- Within this, services rebound most: Our China economists see services consumption rising by 8.5%Y in 2023 versus -1.5%Y in 2022. Demand for goods also increases, but the swing is milder (+7.7%Y in 2023 versus +2.4%Y in 2022). At the risk of simplifying, more people going back to the movies isn't very inflationary; the theatres have capacity, and this consumption doesn't compete with demand elsewhere.

- Supply improves: Reopening should ultimately help to ease pressure on supply chains and improve labour supply in China.

There will be some inflationary impacts. For example, we think that China's reopening will boost oil demand, but even here the impact is back-loaded (see The Oil Manual: Heavy Now, Higher Later, January 11, 2023). Indeed, our economists think that the broader theme across Asia is disinflation. For more, see 2023 Asia Economics Outlook: The Year of Disinflation, November 13, 2022.

Economists at TS Lombard reached a similar conclusion last week, writing that they expect a "limited demand pull" from China's reopening and "even oil prices are unlikely to receive the major demand boost that many expect" to wit:

The composition of growth will determine global demand and inflation spillovers. For the first time, a cyclical recovery in China will be led by household consumption, mainly services. There is clearly a great deal of pent-up demand and savings (about 4% of GDP) following three years of intermittent mobility restrictions. And although we are concerned about the degree of property-related scarring to household (as well as local government and bank) balance sheets, at least in 2023 there is likely to be strong catch-up demand from a very low base. For instance, trips over the first three days of the Spring Festival travel season are up 30% yoy but still only 70% of the 2019 level. Similarly, catering spending last year was just 90% of the 2019 level and tourism spending only 50%. Catch-up growth should be fairly mechanical and lead to increased job hiring (pre-Covid, 25% of all jobs in China were in catering, retail, accommodation and tourism), higher wages and more confidence. Structural problems have not disappeared – far from it – but they will not derail growth in 2023

Globally mild inflation and limited demand pull. A recovery led by household spending on services will support fuel and catering-related commodities, but global spillovers should not be overestimated. Furthermore, demand for industrial metals is likely to come in weaker than current bullish expectations. Chinese imports are driven by investment and industrial demand. The workshop of the world does not need to buy consumer goods overseas; moreover, increases in demand for intermediate goods to meet rising domestic goods consumption are likely to be offset by falling exports and high inventories. Tourism will certainly benefit – Thailand and other regional peers are well placed. However, time will be needed for flight volumes, ticket prices and international Covid restrictions to normalize to near pre-pandemic levels. Official estimates put outbound travel at 70% of pre-Covid levels this year.

Even oil prices are unlikely to receive the major demand boost that many expect. Transportation accounts for just 54% of China’s oil consumption vs 72% in the US and 68% in the EU. Petrochemicals constitute a much larger share, at 42%, with related China imports generally led by construction and export-oriented manufacturing (lots of plastic). Last year, net oil and refined petroleum imports were 8% lower by volume than the pre-pandemic peak – infrastructure and export-oriented manufacturing partly offset lower mobility and less property construction. Demand drivers should switch this year, with travel rising and property less negative, while infrastructure and manufacturing slow. The certain outcome is an increase in oil demand: we estimate a 5-8% increase in net import volumes, which, however, is unlikely to cause oil prices to surge, especially as China is buying at a discount from Russia. An inflationary impulse is coming from the PRC but will be domestically focused and unlikely to trouble the PBoC, let alone the Fed.

Ironically, one of the reasons why a major monetary stimulus in China will not lead to surge in inflation abroad is that since 2015, it has become much harder and more expensive to move money offshore.

The impetus to move funds is now arguably greater than it was in the aftermath of the surprise FX devaluation. The currency move was a one-off shock, “Common Prosperity” is here to stay. Outbound tourism offers one avenue to mask capital flight. Data on capital outflows are sparse. We can observe surface-level changes – for example, increased “golden visa” issuance to Chinese nationals – but the scale is hard to gauge. Balance of payments data are a metric of potential outflows. We think tourism spending alone is likely to reach US$40bn in quarterly outflows by the end of H1/23 based on pre-Covid trends. Net errors and omissions, another proxy for capital flight, could rise to US$50bn if there is a return to the 2017-2019 quarterly average. Given a goods surplus of US$200bn in Q3/22, this will not send the Chinese current account into deficit; but, combined with a narrower trade surplus (domestic imports rising modestly, global demand slumping), it will bring downward pressure to bear on RMB from late Q2/23 onwards.

Translation: after China plugged the Great Firewall in 2015/2016 and made it next to impossible to use bitcoin to shuffle cash offshore, inflation has been far more localized. Of course, the counterargument also stands: if China loses control of domestic inflation and hopes to export higher prices offshore, it will then quietly open all those locks it implemented in recent years to make money laundering abroad using crypto impossible.

More in the full reports available to pro subs in the usual place.

Monday’s furious rally, which among other things was facilitated by the Sunday report from WSJ Fed mouthpiece Nick Timiraos that a 25bps Feb 1 rate hike by the Fed is a done deal, hit an airpocket just after 2pm when in the latest tweet from Timiraos – whose every utterance now moves markets, especially during the Fed blackout period – and in which the WSJ reporter noted that “Just when signs point to easing inflation worldwide, China’s economic reopening after years of strict pandemic controls is raising questions about whether it could spur costs higher again.”

Just when signs point to easing inflation worldwide, China’s economic reopening after years of strict pandemic controls is raising questions about whether it could spur costs higher again https://t.co/NA8Wr3l2L3

— Nick Timiraos (@NickTimiraos) January 23, 2023

Needless to say, China’s economic reopening is a very sensitive issue: on one hand, there are those who argue easier access to reopened Chinese markets will mean smoother supply chains and cheaper goods (and transit) contributing to the current disinflation; on the other hand, should China’s reopening turn out to be “hot” and should Beijing end up exporting too much inflation (as it has in the past), it could reverse any “pause” or “pivot” plans the Fed has, and instead force it to double down on tightening later in 2023.

Yes, and this is similar to what Powell said when asked about reopening effects last month. The two offset each other to some effect, but the exact net effect is very uncertain. https://t.co/yHWtXwz4fV pic.twitter.com/GZdBlVCjna

— Nick Timiraos (@NickTimiraos) January 23, 2023

While we will have much more to say on this topic in the coming days, the initial consensus on Wall Street is that a Chinese reopening will not, in fact, be inflationary. Take last week’s Cross-Asset Dispatches note from Morgan Stanley, in which strategist Andrew Sheets explains why expectations that China’s reopening will be inflationary will disappoint. We excerpt from his note below:

We don’t think that China’s reopening will be inflationary

Wage growth is one risk to the Morgan Stanley ‘inflation falls’ thesis. Another is China’s reopening from Covid-zero, which has been increasingly aggressive. Our forecasts imply that this reopening will be successful, with our economists optimistic on China growth, and our strategists optimistic on China equities and FX.

But if the world’s second-largest economy successfully reopens from Covid, won’t that drive more inflationary pressure in 2023?

Not necessarily. Our economists see a few considerations:

- Private consumption sees the largest rebound: Private consumption in China saw the largest drop-off as a result of Covid-zero, and has the most to gain from this ending, especially with high private savings. This demand competes less at the international level than more commodity-heavy public investment.

- Within this, services rebound most: Our China economists see services consumption rising by 8.5%Y in 2023 versus -1.5%Y in 2022. Demand for goods also increases, but the swing is milder (+7.7%Y in 2023 versus +2.4%Y in 2022). At the risk of simplifying, more people going back to the movies isn’t very inflationary; the theatres have capacity, and this consumption doesn’t compete with demand elsewhere.

- Supply improves: Reopening should ultimately help to ease pressure on supply chains and improve labour supply in China.

There will be some inflationary impacts. For example, we think that China’s reopening will boost oil demand, but even here the impact is back-loaded (see The Oil Manual: Heavy Now, Higher Later, January 11, 2023). Indeed, our economists think that the broader theme across Asia is disinflation. For more, see 2023 Asia Economics Outlook: The Year of Disinflation, November 13, 2022.

Economists at TS Lombard reached a similar conclusion last week, writing that they expect a “limited demand pull” from China’s reopening and “even oil prices are unlikely to receive the major demand boost that many expect” to wit:

The composition of growth will determine global demand and inflation spillovers. For the first time, a cyclical recovery in China will be led by household consumption, mainly services. There is clearly a great deal of pent-up demand and savings (about 4% of GDP) following three years of intermittent mobility restrictions. And although we are concerned about the degree of property-related scarring to household (as well as local government and bank) balance sheets, at least in 2023 there is likely to be strong catch-up demand from a very low base. For instance, trips over the first three days of the Spring Festival travel season are up 30% yoy but still only 70% of the 2019 level. Similarly, catering spending last year was just 90% of the 2019 level and tourism spending only 50%. Catch-up growth should be fairly mechanical and lead to increased job hiring (pre-Covid, 25% of all jobs in China were in catering, retail, accommodation and tourism), higher wages and more confidence. Structural problems have not disappeared – far from it – but they will not derail growth in 2023

Globally mild inflation and limited demand pull. A recovery led by household spending on services will support fuel and catering-related commodities, but global spillovers should not be overestimated. Furthermore, demand for industrial metals is likely to come in weaker than current bullish expectations. Chinese imports are driven by investment and industrial demand. The workshop of the world does not need to buy consumer goods overseas; moreover, increases in demand for intermediate goods to meet rising domestic goods consumption are likely to be offset by falling exports and high inventories. Tourism will certainly benefit – Thailand and other regional peers are well placed. However, time will be needed for flight volumes, ticket prices and international Covid restrictions to normalize to near pre-pandemic levels. Official estimates put outbound travel at 70% of pre-Covid levels this year.

Even oil prices are unlikely to receive the major demand boost that many expect. Transportation accounts for just 54% of China’s oil consumption vs 72% in the US and 68% in the EU. Petrochemicals constitute a much larger share, at 42%, with related China imports generally led by construction and export-oriented manufacturing (lots of plastic). Last year, net oil and refined petroleum imports were 8% lower by volume than the pre-pandemic peak – infrastructure and export-oriented manufacturing partly offset lower mobility and less property construction. Demand drivers should switch this year, with travel rising and property less negative, while infrastructure and manufacturing slow. The certain outcome is an increase in oil demand: we estimate a 5-8% increase in net import volumes, which, however, is unlikely to cause oil prices to surge, especially as China is buying at a discount from Russia. An inflationary impulse is coming from the PRC but will be domestically focused and unlikely to trouble the PBoC, let alone the Fed.

Ironically, one of the reasons why a major monetary stimulus in China will not lead to surge in inflation abroad is that since 2015, it has become much harder and more expensive to move money offshore.

The impetus to move funds is now arguably greater than it was in the aftermath of the surprise FX devaluation. The currency move was a one-off shock, “Common Prosperity” is here to stay. Outbound tourism offers one avenue to mask capital flight. Data on capital outflows are sparse. We can observe surface-level changes – for example, increased “golden visa” issuance to Chinese nationals – but the scale is hard to gauge. Balance of payments data are a metric of potential outflows. We think tourism spending alone is likely to reach US$40bn in quarterly outflows by the end of H1/23 based on pre-Covid trends. Net errors and omissions, another proxy for capital flight, could rise to US$50bn if there is a return to the 2017-2019 quarterly average. Given a goods surplus of US$200bn in Q3/22, this will not send the Chinese current account into deficit; but, combined with a narrower trade surplus (domestic imports rising modestly, global demand slumping), it will bring downward pressure to bear on RMB from late Q2/23 onwards.

Translation: after China plugged the Great Firewall in 2015/2016 and made it next to impossible to use bitcoin to shuffle cash offshore, inflation has been far more localized. Of course, the counterargument also stands: if China loses control of domestic inflation and hopes to export higher prices offshore, it will then quietly open all those locks it implemented in recent years to make money laundering abroad using crypto impossible.

More in the full reports available to pro subs in the usual place.

Loading…