By John Kemp, senior energy analyst at Reuters

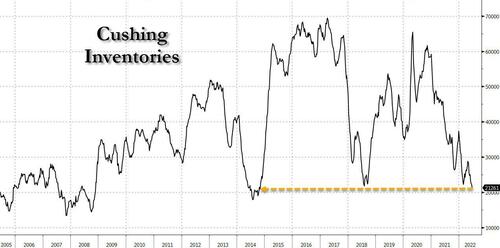

With global inventories steadily falling and spare capacity eroding, the oil market resembles a geological fault line in which stress is quietly accumulating and will eventually be relieved by an earthquake of as yet unknown magnitude.

The most likely stress relief will come from a deceleration in oil consumption as a result of a recession or mid-cycle manufacturing slowdown in the major oil consuming economies of North America, Europe and Asia.

Economic growth is already slowing in the United States and faltering in Europe and China under the combined impact of accelerating inflation, rising interest rates and coronavirus controls. Financial conditions are tightening rapidly as central banks raise interest rates and commercial banks enforce tougher lending standards.

Unlike previous cyclical slowdowns, central banks are likely to continue tightening financial conditions as the economy slows to snuff out inflation.

The alternative is for a sharp acceleration of production ― meaning more output from OPEC members, U.S. shale producers, other non-OPEC suppliers, or currently sanctioned countries. Most OPEC members are already producing at full capacity, with the exception of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

The precise amount of spare capacity available in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates is disputed given the secrecy which surrounds their production systems. But it is unlikely to be much more than around 1 million barrels per day (bpd) based on historic production rates (“Can Saudi Aramco Meet Its Oil Production Promises?”, Bloomberg, June 29).

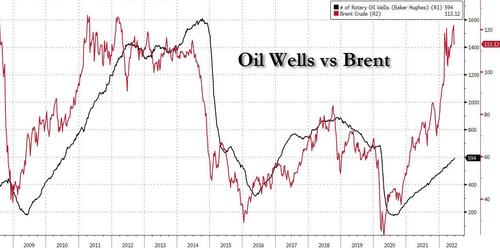

U.S. shale producers are already increasing drilling rates, which will translate into higher production over the next 6-12 months, once the wells have been drilled, fractured and linked up to pipeline systems.

The largest shale producers remain committed to restraining output growth to avoid flooding the market and return capital to shareholders, which is likely to limit growth from this source.

Non-OPEC non-shale producers (NONS) are expected to increase production by under 1 million bpd in both 2022 and 2023 (“EIA forecasts growing liquid fuels production in Brazil, Canada and China”, EIA, June 17).

The only other source of increased production would come from easing sanctions on Venezuela, Iran or Russia, which could add several million barrels daily to the market depending on which sanctions were relaxed.

ACCUMULATING STRESS

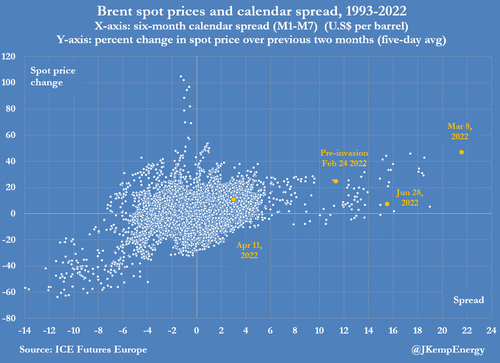

Brent’s spot price and calendar spreads are sending contrasting signals about the tightness of oil supplies, implying the market is storing up volatility which is likely to be unleashed over the next few months.

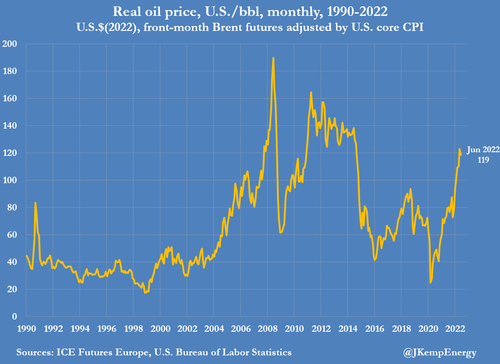

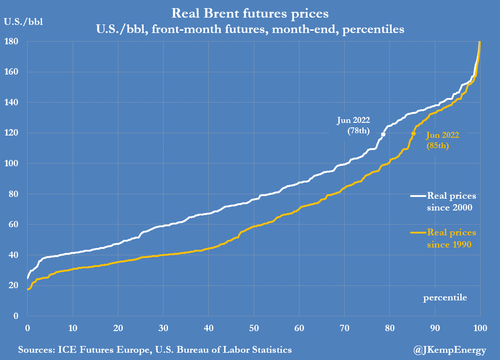

Front-month futures prices are high, but not extremely so once adjusted for inflation, lying in the 85th percentile for all months since 1990 and the 78th percentile for all months since 2000.

The implication is the market is short of petroleum but the shortfall is not (yet) critical and expected to be resolved relatively easily by an increase in production, a reduction in consumption, or both.

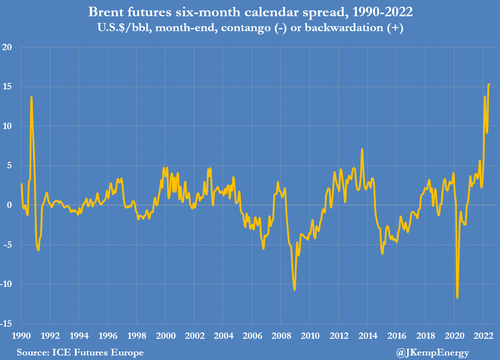

But Brent’s six-month calendar spread, usually seen as a clearer signal about the balance between production, consumption, inventories and spare capacity, is trading near record levels.

Brent spreads are signalling the market is already exceptionally tight, with shortages becoming critical and difficult to relieve without a massive increase in output, a recession-driven fall in consumption, or both.

Other calendar spreads, including the very short-term dated Brent spreads for cargoes scheduled to load in the next few weeks, and Murban crude futures, the benchmark in Asia, are already at record levels. The tightness in some of these short-term spreads is likely exaggerated by squeezes, so the price structures should be interpreted with care, but squeezes would not be possible if the market was not under-supplied.

Critical calendar spreads are signalling an extreme shortage of crude - even though the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) is discharging 1 million barrels per day until the end of October.

Spreads signal the production-consumption balance is expected to be far tighter than in either 2012-2014 or 2007-2008, the last time that real oil prices were this high.

The contradiction between spot prices and spreads must eventually be resolved, which will likely induce significant volatility: either spot prices must rise to align with tightness implied by the calendar spreads, or the spreads must soften to match the more evenly balanced market implied by spot prices.

TIME TO CHOOSE

The oil market is confronting policymakers with a menu of options. But each of them carries a high cost in terms of diplomacy, domestic politics, the economy, or all three, making them unpalatable for decision-makers. This explains why "clever" technical solutions that appear to avoid these hard choices are so popular at the moment in the United States and the European Union.

The proposed price cap on Russia’s petroleum exports is designed to reduce Russia’s revenues without reducing oil supply, raising prices, increasing the need for a recession, or relaxing sanctions on Iran or Venezuela. But the feasibility of these technical solutions falls as their complexity increases.

It is like going into a restaurant, ordering all the items on the menu, and then being surprised the eventual bill is so high.

In the recent past, stringent U.S.-led sanctions on Iran between 2012 and 2015 contributed to the period of very high real prices between 2012 and 2014. Sanctions have invariably driven up energy prices for consumers unless there are alternative supplies readily available to make up the deficit (“Energy sanctions and the impact on prices for consumers”, Kemp, June 2022).

In the current market, there is very limited spare capacity, unless and until a recessionary slowdown in the global economy and oil consumption creates some more slack.

U.S. and EU policymakers must therefore choose - tougher sanctions on Russia; easier sanctions on Venezuela and Iran; faster production growth from Saudi Arabia and the UAE; faster growth from U.S. shale; or a deeper recession.

By John Kemp, senior energy analyst at Reuters

With global inventories steadily falling and spare capacity eroding, the oil market resembles a geological fault line in which stress is quietly accumulating and will eventually be relieved by an earthquake of as yet unknown magnitude.

The most likely stress relief will come from a deceleration in oil consumption as a result of a recession or mid-cycle manufacturing slowdown in the major oil consuming economies of North America, Europe and Asia.

Economic growth is already slowing in the United States and faltering in Europe and China under the combined impact of accelerating inflation, rising interest rates and coronavirus controls. Financial conditions are tightening rapidly as central banks raise interest rates and commercial banks enforce tougher lending standards.

Unlike previous cyclical slowdowns, central banks are likely to continue tightening financial conditions as the economy slows to snuff out inflation.

The alternative is for a sharp acceleration of production ― meaning more output from OPEC members, U.S. shale producers, other non-OPEC suppliers, or currently sanctioned countries. Most OPEC members are already producing at full capacity, with the exception of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

The precise amount of spare capacity available in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates is disputed given the secrecy which surrounds their production systems. But it is unlikely to be much more than around 1 million barrels per day (bpd) based on historic production rates (“Can Saudi Aramco Meet Its Oil Production Promises?”, Bloomberg, June 29).

U.S. shale producers are already increasing drilling rates, which will translate into higher production over the next 6-12 months, once the wells have been drilled, fractured and linked up to pipeline systems.

The largest shale producers remain committed to restraining output growth to avoid flooding the market and return capital to shareholders, which is likely to limit growth from this source.

Non-OPEC non-shale producers (NONS) are expected to increase production by under 1 million bpd in both 2022 and 2023 (“EIA forecasts growing liquid fuels production in Brazil, Canada and China”, EIA, June 17).

The only other source of increased production would come from easing sanctions on Venezuela, Iran or Russia, which could add several million barrels daily to the market depending on which sanctions were relaxed.

ACCUMULATING STRESS

Brent’s spot price and calendar spreads are sending contrasting signals about the tightness of oil supplies, implying the market is storing up volatility which is likely to be unleashed over the next few months.

Front-month futures prices are high, but not extremely so once adjusted for inflation, lying in the 85th percentile for all months since 1990 and the 78th percentile for all months since 2000.

The implication is the market is short of petroleum but the shortfall is not (yet) critical and expected to be resolved relatively easily by an increase in production, a reduction in consumption, or both.

But Brent’s six-month calendar spread, usually seen as a clearer signal about the balance between production, consumption, inventories and spare capacity, is trading near record levels.

Brent spreads are signalling the market is already exceptionally tight, with shortages becoming critical and difficult to relieve without a massive increase in output, a recession-driven fall in consumption, or both.

Other calendar spreads, including the very short-term dated Brent spreads for cargoes scheduled to load in the next few weeks, and Murban crude futures, the benchmark in Asia, are already at record levels. The tightness in some of these short-term spreads is likely exaggerated by squeezes, so the price structures should be interpreted with care, but squeezes would not be possible if the market was not under-supplied.

Critical calendar spreads are signalling an extreme shortage of crude – even though the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) is discharging 1 million barrels per day until the end of October.

Spreads signal the production-consumption balance is expected to be far tighter than in either 2012-2014 or 2007-2008, the last time that real oil prices were this high.

The contradiction between spot prices and spreads must eventually be resolved, which will likely induce significant volatility: either spot prices must rise to align with tightness implied by the calendar spreads, or the spreads must soften to match the more evenly balanced market implied by spot prices.

TIME TO CHOOSE

The oil market is confronting policymakers with a menu of options. But each of them carries a high cost in terms of diplomacy, domestic politics, the economy, or all three, making them unpalatable for decision-makers. This explains why “clever” technical solutions that appear to avoid these hard choices are so popular at the moment in the United States and the European Union.

The proposed price cap on Russia’s petroleum exports is designed to reduce Russia’s revenues without reducing oil supply, raising prices, increasing the need for a recession, or relaxing sanctions on Iran or Venezuela. But the feasibility of these technical solutions falls as their complexity increases.

It is like going into a restaurant, ordering all the items on the menu, and then being surprised the eventual bill is so high.

In the recent past, stringent U.S.-led sanctions on Iran between 2012 and 2015 contributed to the period of very high real prices between 2012 and 2014. Sanctions have invariably driven up energy prices for consumers unless there are alternative supplies readily available to make up the deficit (“Energy sanctions and the impact on prices for consumers”, Kemp, June 2022).

In the current market, there is very limited spare capacity, unless and until a recessionary slowdown in the global economy and oil consumption creates some more slack.

U.S. and EU policymakers must therefore choose – tougher sanctions on Russia; easier sanctions on Venezuela and Iran; faster production growth from Saudi Arabia and the UAE; faster growth from U.S. shale; or a deeper recession.