By Rachel Premack of FreightWaves

The phrase “freight broker” is rather boring, I will admit it. As snoozy as those words may make you feel, these brokers are key to making sure stuff gets on trucks and across the country.

Since deregulation wrested trucking from the control of the federal government in 1980, freight brokerages have become a trucking necessity. Every imaginable company — ranging from General Mills to Amazon to Starbucks — relies on freight brokers to place loads on trucks every day.

One major transporter has tried to eschew freight brokers for years: the U.S. Postal Service. The Postal Service spent nearly $10 billion moving letters and boxes in fiscal year 2021. Most of that expense is on trucks, but there are also FedEx and UPS planes, trains and even ships.

It’s not known when exactly the Postal Service started to use freight brokers, but attorney David P. Hendel only began including brokers like C.H. Robinson on his essential top 150 Postal Service contractor list in 2013.

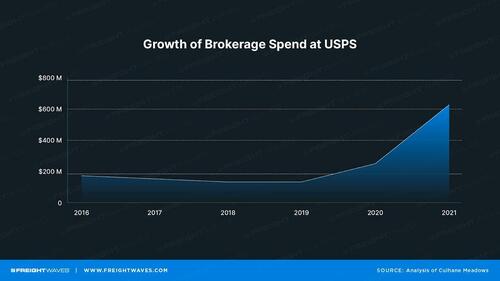

A FreightWaves analysis of the Postal Service’s top suppliers reveals that the agency’s reliance on brokers has boomed in the past nine years. The Postal Service counted three brokerage firms among its top 150 suppliers in fiscal year 2013, totaling $85 million. By fiscal year 2021, at least 11 firms that primarily provide brokerage services were on that list, representing a spend of more than $620 million.

"The Postal Service is re-examining its network both long-haul and even local,” said Hendel, a partner at Culhane Meadows who specializes in government contracting work. “I think the Postal Service now views the carriage of mail as a commodity, rather than as a special service. It feels like it maybe should be taking advantage of the larger commercial marketplace.”

By using brokers, outsiders believe the Postal Service can save cash. Public data indicates that the Postal Service has intensified its freight broker spend under Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, who assumed his role in June 2020. DeJoy was previously CEO of New Breed Logistics, a long-time USPS contractor, which was sold to XPO Logistics in 2014.

This cost-saving tactic won’t surprise those who have followed DeJoy’s tenure. Under his leadership, the Postal Service has doubled down on “modernizing” its transportation network. This partially means implementing tools that private-sector shippers have used for years, like a digital load board where freight bids are posted and a digital transportation management system.

A USPS spokesperson declined to answer answers to a list of questions about the Postal Service’s new brokerage strategy, but provided a statement.

“The Postal Service continues to onboard new carriers to help us deliver as part of our Delivering for America 10-year plan for achieving financial sustainability and service excellence,” the spokesperson wrote in an emailed statement. “These carriers are both asset based and non-asset based providers. The Postal Service also has one of the largest private fleets in the industry that we rely on to move freight in certain regions. When our fleet cannot handle the volume, we tender to our partner carriers. Depending on the specific circumstances to move the load, we will use either a contracted carrier or move via a spot market transaction.”

Outsiders have characterized DeJoy as a fella who wants to run the Postal Service like a corporation, not a government service. That’s a good thing if you’re, say, Nevada-based ITS Logistics, which saw its Postal Service contract nearly double from fiscal year 2020 to 2021. But it’s not so good if you’re one of the Postal Service’s hundreds of long-haul trucking partners — which are likely set to lose business as the Postal Service reimagines its trucking network.

“I think his impact is a sea change in terms of the way in which the Postal Service thinks about transportation,” said Greg Reed, who is the executive director of the National Star Route Mail Contractors Association, which is the trade organization that represents Postal Service transportation contractors. ”It’s obviously driven from his background in logistics and in the brokerage world. It’s driven from his knowledge and experience that there is no sophisticated supply chain that doesn’t incorporate brokers into their model. That’s about effiency, capacity and pricing.”

Wait, what the heck is a freight broker?

For the logistics neophytes among us, let’s briefly talk about what a freight broker is.

The phrase freight broker usually refers to trucking. There are brokers, of course, to place freight on airplanes, rail and ships. Especially for international movements, they’re usually called “freight forwarders.” The trucking industry, through sheer force of will, has mostly claimed the phrase “freight broker” for itself, even though there are indeed many types of transportation brokers.

Brokers handle most varieties of trucking freight, whether it was picked up on the so-called “spot market” or was contracted out months in advance. But it wasn’t always like this. Before 1980, regular, scheduled runs were the norm, in part because the federal government dictated the rate of each trucking route.

Decades ago, brokers were an anomaly. The former head of the Transportation Intermediaries Association estimated that there were only 14 licensed brokers in 1980. That exploded to more than 10,000 in 2005, he said at the time.

Nearly two decades ago, the truck brokerage market was worth some $50 billion. Today, it’s worth around $186 billion, according to the TIA.

One reason that freight brokers have become so common is that there are way too many trucking companies for each retailer, manufacturer, farmer or whatever to form relationships with. So they turn to brokers to figure out who to work with.

There were some 17,000 trucking companies by the end of the 1970s, when brokers were still unusual. But today, hundreds of thousands of firms comprise trucking. Many have a whopping single truck. These small companies, also called “owner-operators,” mostly run on what’s called the spot market, where they pick up jobs as it’s convenient. They don’t have regular schedules or customers.

The other side is the contract market, where a trucking company pledges to execute, say, eight runs a week shuttling goods between Des Moines, Iowa, and Detroit for a year.

These contracts are kind of lies, though — and both sides know it when they sign it. The retailer, manufacturer, farmer or whatever might need far more or far fewer trucks running between Des Moines and Detroit on a given week. What really ends up happening is uncertain.

The Postal Service’s old-timey transportation system

Over the decades, it’s become the norm for trucking companies and their customers to ditch the stipulations of their contracts. The Postal Service hasn’t kept up with that trend. And, as a result, its transportation network is unusually redundant. Reed said the complication of separating letter mail versus boxes has left some Postal Service trucks shuttling down the highway empty or with a single box or two inside.

Not only does the Postal Service actually stick to its contracts, it works with a lot more contractors than other shippers. Rather than heavily relying on brokerage firms to allocate spot or contract freight, the Postal Service maintains decades-long contracts with trucking firms that mostly just haul freight for the mail agency. The agency allocates about 10% of its total transportation spend on in-house truck drivers, all of whom are unionized.

One example of that is 10 Roads Express, which says on its website that it grew from a one-truck operation in 1946 to a 3,500-truck operation today through hauling U.S. mail. In the fiscal year 2021, the Iowa trucker made $540 million off its Postal Service business.

Regular routes seemed to allow Postal Service carriers to eschew technologies that other carriers had to adopt upward of a decade ago. As of the past two years, the Postal Service has pushed features including a digital load board and an online transportation management system, Reed said.

Another major factor of DeJoy’s cost-saving tactics is moving freight that would normally end up on a cargo plane to a truck instead. DeJoy recently hired a former New Breed Logistics executive to help lead this transformation.

The Postal Service is trying to get better at not following its contracts, though. It has devised a new type of contract with a feature called “dynamic routing optimization.” With those contracts, the Postal Service assesses each week if it needs more or fewer trucks on a certain route.

The other side of the Postal Service’s move away from contract freight is, of course, working with brokers.

The Postal Service could save a lot of money with freight brokers, but it’s a knock on its longtime carriers

Implementing new contracts and other technologies could mean cost savings at the Postal Service, but it’s spooky for long-time carriers — especially because these new products aren’t always perfect. One trucking contractor told the Washington Post last year that the Postal Service’s new software has cost them $110 million and sparked hundreds of layoffs.

“The biggest burden in general is implementing that technology and those practices,” Reed said of long-time contractors.

The Postal Service has already ditched thousands of carriers as it’s streamlined operations, according to longtime parcel expert Satish Jindel. In 2014, the Postal Service worked with about 4,000 highway contractors. Now that’s around 1,700. That’s not because the Postal Service is trying to reduce its reliance on trucking; the Postal Service is actually focused on moving more freight off pricey cargo planes and onto trucks.

“They need larger carriers,” Jindel said. “They don’t have the ability to use small mom-and-pop carriers to rely on in the past.”

That explains why the Postal Service has turned to brokers to work with smaller trucking companies. In 2021, the Postal Service counted XPO Logistics, C.H. Robinson and ITS Logistics among its largest truck broker providers. (XPO and C.H. Robinson declined to comment for this piece, while Eve and ITS did not respond to a request for comment.)

What’s more, leaning on the spot market means you can bid truck space as needed, rather than needing a yearslong contract with carriers all over the country. That should seemingly push the Postal Service toward an efficient, modernized transportation network.

However, perhaps 2021, famously the year that spot market rates shot to the moon, was a very bad year to turbocharge the usage of freight brokers. According to one analysis of public data, the Postal Service paid more than $50 million in extra trip dollars in January 2022, more than tenfold the spend from 2021 or 2020.

“Anytime they can have a direct contract with a carrier, that is always a better service at a better price, because they are then buying that service through the spot market,” Jindel said.

But, Hendel said he believes it’s unlikely that the cost-conscious Postal Service would continue to pursue freight brokerage if it didn’t have the potential to slash costs.

Even amid the move to modernize the Postal Service, Hendel doubts the agency would ever want to ditch its old-fashioned contract carrier model — just as UPS or FedEx hasn’t opened itself entirely up to the spot market. The risk to the mail system would be too large.

“I think that could be a dangerous thing because you don’t have the dedicated reliable providers you have today and you open yourself up to spot market issues,” Hendel said. “I don’t think the Postal Service will ever be well-served by relying exclusively on brokers — that would be a recipe for disaster.”

By Rachel Premack of FreightWaves

The phrase “freight broker” is rather boring, I will admit it. As snoozy as those words may make you feel, these brokers are key to making sure stuff gets on trucks and across the country.

Since deregulation wrested trucking from the control of the federal government in 1980, freight brokerages have become a trucking necessity. Every imaginable company — ranging from General Mills to Amazon to Starbucks — relies on freight brokers to place loads on trucks every day.

One major transporter has tried to eschew freight brokers for years: the U.S. Postal Service. The Postal Service spent nearly $10 billion moving letters and boxes in fiscal year 2021. Most of that expense is on trucks, but there are also FedEx and UPS planes, trains and even ships.

It’s not known when exactly the Postal Service started to use freight brokers, but attorney David P. Hendel only began including brokers like C.H. Robinson on his essential top 150 Postal Service contractor list in 2013.

A FreightWaves analysis of the Postal Service’s top suppliers reveals that the agency’s reliance on brokers has boomed in the past nine years. The Postal Service counted three brokerage firms among its top 150 suppliers in fiscal year 2013, totaling $85 million. By fiscal year 2021, at least 11 firms that primarily provide brokerage services were on that list, representing a spend of more than $620 million.

“The Postal Service is re-examining its network both long-haul and even local,” said Hendel, a partner at Culhane Meadows who specializes in government contracting work. “I think the Postal Service now views the carriage of mail as a commodity, rather than as a special service. It feels like it maybe should be taking advantage of the larger commercial marketplace.”

By using brokers, outsiders believe the Postal Service can save cash. Public data indicates that the Postal Service has intensified its freight broker spend under Postmaster General Louis DeJoy, who assumed his role in June 2020. DeJoy was previously CEO of New Breed Logistics, a long-time USPS contractor, which was sold to XPO Logistics in 2014.

This cost-saving tactic won’t surprise those who have followed DeJoy’s tenure. Under his leadership, the Postal Service has doubled down on “modernizing” its transportation network. This partially means implementing tools that private-sector shippers have used for years, like a digital load board where freight bids are posted and a digital transportation management system.

A USPS spokesperson declined to answer answers to a list of questions about the Postal Service’s new brokerage strategy, but provided a statement.

“The Postal Service continues to onboard new carriers to help us deliver as part of our Delivering for America 10-year plan for achieving financial sustainability and service excellence,” the spokesperson wrote in an emailed statement. “These carriers are both asset based and non-asset based providers. The Postal Service also has one of the largest private fleets in the industry that we rely on to move freight in certain regions. When our fleet cannot handle the volume, we tender to our partner carriers. Depending on the specific circumstances to move the load, we will use either a contracted carrier or move via a spot market transaction.”

Outsiders have characterized DeJoy as a fella who wants to run the Postal Service like a corporation, not a government service. That’s a good thing if you’re, say, Nevada-based ITS Logistics, which saw its Postal Service contract nearly double from fiscal year 2020 to 2021. But it’s not so good if you’re one of the Postal Service’s hundreds of long-haul trucking partners — which are likely set to lose business as the Postal Service reimagines its trucking network.

“I think his impact is a sea change in terms of the way in which the Postal Service thinks about transportation,” said Greg Reed, who is the executive director of the National Star Route Mail Contractors Association, which is the trade organization that represents Postal Service transportation contractors. ”It’s obviously driven from his background in logistics and in the brokerage world. It’s driven from his knowledge and experience that there is no sophisticated supply chain that doesn’t incorporate brokers into their model. That’s about effiency, capacity and pricing.”

Wait, what the heck is a freight broker?

For the logistics neophytes among us, let’s briefly talk about what a freight broker is.

The phrase freight broker usually refers to trucking. There are brokers, of course, to place freight on airplanes, rail and ships. Especially for international movements, they’re usually called “freight forwarders.” The trucking industry, through sheer force of will, has mostly claimed the phrase “freight broker” for itself, even though there are indeed many types of transportation brokers.

Brokers handle most varieties of trucking freight, whether it was picked up on the so-called “spot market” or was contracted out months in advance. But it wasn’t always like this. Before 1980, regular, scheduled runs were the norm, in part because the federal government dictated the rate of each trucking route.

Decades ago, brokers were an anomaly. The former head of the Transportation Intermediaries Association estimated that there were only 14 licensed brokers in 1980. That exploded to more than 10,000 in 2005, he said at the time.

Nearly two decades ago, the truck brokerage market was worth some $50 billion. Today, it’s worth around $186 billion, according to the TIA.

One reason that freight brokers have become so common is that there are way too many trucking companies for each retailer, manufacturer, farmer or whatever to form relationships with. So they turn to brokers to figure out who to work with.

There were some 17,000 trucking companies by the end of the 1970s, when brokers were still unusual. But today, hundreds of thousands of firms comprise trucking. Many have a whopping single truck. These small companies, also called “owner-operators,” mostly run on what’s called the spot market, where they pick up jobs as it’s convenient. They don’t have regular schedules or customers.

The other side is the contract market, where a trucking company pledges to execute, say, eight runs a week shuttling goods between Des Moines, Iowa, and Detroit for a year.

These contracts are kind of lies, though — and both sides know it when they sign it. The retailer, manufacturer, farmer or whatever might need far more or far fewer trucks running between Des Moines and Detroit on a given week. What really ends up happening is uncertain.

The Postal Service’s old-timey transportation system

Over the decades, it’s become the norm for trucking companies and their customers to ditch the stipulations of their contracts. The Postal Service hasn’t kept up with that trend. And, as a result, its transportation network is unusually redundant. Reed said the complication of separating letter mail versus boxes has left some Postal Service trucks shuttling down the highway empty or with a single box or two inside.

Not only does the Postal Service actually stick to its contracts, it works with a lot more contractors than other shippers. Rather than heavily relying on brokerage firms to allocate spot or contract freight, the Postal Service maintains decades-long contracts with trucking firms that mostly just haul freight for the mail agency. The agency allocates about 10% of its total transportation spend on in-house truck drivers, all of whom are unionized.

One example of that is 10 Roads Express, which says on its website that it grew from a one-truck operation in 1946 to a 3,500-truck operation today through hauling U.S. mail. In the fiscal year 2021, the Iowa trucker made $540 million off its Postal Service business.

Regular routes seemed to allow Postal Service carriers to eschew technologies that other carriers had to adopt upward of a decade ago. As of the past two years, the Postal Service has pushed features including a digital load board and an online transportation management system, Reed said.

Another major factor of DeJoy’s cost-saving tactics is moving freight that would normally end up on a cargo plane to a truck instead. DeJoy recently hired a former New Breed Logistics executive to help lead this transformation.

The Postal Service is trying to get better at not following its contracts, though. It has devised a new type of contract with a feature called “dynamic routing optimization.” With those contracts, the Postal Service assesses each week if it needs more or fewer trucks on a certain route.

The other side of the Postal Service’s move away from contract freight is, of course, working with brokers.

The Postal Service could save a lot of money with freight brokers, but it’s a knock on its longtime carriers

Implementing new contracts and other technologies could mean cost savings at the Postal Service, but it’s spooky for long-time carriers — especially because these new products aren’t always perfect. One trucking contractor told the Washington Post last year that the Postal Service’s new software has cost them $110 million and sparked hundreds of layoffs.

“The biggest burden in general is implementing that technology and those practices,” Reed said of long-time contractors.

The Postal Service has already ditched thousands of carriers as it’s streamlined operations, according to longtime parcel expert Satish Jindel. In 2014, the Postal Service worked with about 4,000 highway contractors. Now that’s around 1,700. That’s not because the Postal Service is trying to reduce its reliance on trucking; the Postal Service is actually focused on moving more freight off pricey cargo planes and onto trucks.

“They need larger carriers,” Jindel said. “They don’t have the ability to use small mom-and-pop carriers to rely on in the past.”

That explains why the Postal Service has turned to brokers to work with smaller trucking companies. In 2021, the Postal Service counted XPO Logistics, C.H. Robinson and ITS Logistics among its largest truck broker providers. (XPO and C.H. Robinson declined to comment for this piece, while Eve and ITS did not respond to a request for comment.)

What’s more, leaning on the spot market means you can bid truck space as needed, rather than needing a yearslong contract with carriers all over the country. That should seemingly push the Postal Service toward an efficient, modernized transportation network.

However, perhaps 2021, famously the year that spot market rates shot to the moon, was a very bad year to turbocharge the usage of freight brokers. According to one analysis of public data, the Postal Service paid more than $50 million in extra trip dollars in January 2022, more than tenfold the spend from 2021 or 2020.

“Anytime they can have a direct contract with a carrier, that is always a better service at a better price, because they are then buying that service through the spot market,” Jindel said.

But, Hendel said he believes it’s unlikely that the cost-conscious Postal Service would continue to pursue freight brokerage if it didn’t have the potential to slash costs.

Even amid the move to modernize the Postal Service, Hendel doubts the agency would ever want to ditch its old-fashioned contract carrier model — just as UPS or FedEx hasn’t opened itself entirely up to the spot market. The risk to the mail system would be too large.

“I think that could be a dangerous thing because you don’t have the dedicated reliable providers you have today and you open yourself up to spot market issues,” Hendel said. “I don’t think the Postal Service will ever be well-served by relying exclusively on brokers — that would be a recipe for disaster.”