By George Lei, Bloomberg Markets Live commentator and reporter

Strict capital controls made it impossible for several European companies to send dividends abroad and a Japanese beverage maker could not get paid due to “tougher restrictions on cross-border wire transactions.” This is not Russia in 2022, but China in late 2016 and early 2017, when the yuan plunged toward 7 per dollar.

Those types of curbs could soon be brought back as part of Beijing’s arsenal to manage currency depreciation, especially in a context similar to 2016-17: Once again, the Fed hikes and capital flees. Besides the headline exchange rate, how much and how quickly money can leave China will become equally, if not more, important.

Global portfolio managers, foreign businesses and the local rich are either leaving China or bringing much less capital onshore. The nation suffered an unprecedented outflow from bond and stock investors in March and net selling continued into April, according to estimates from the International Institute of Finance.

Total capital outflows, including errors and omissions, may surge to about $300b this year from $129b in 2021, IIF said in a report last week. While that figure is well below $725b, IIF’s estimate for 2016, Beijing’s options for combating it are much narrower this time around.

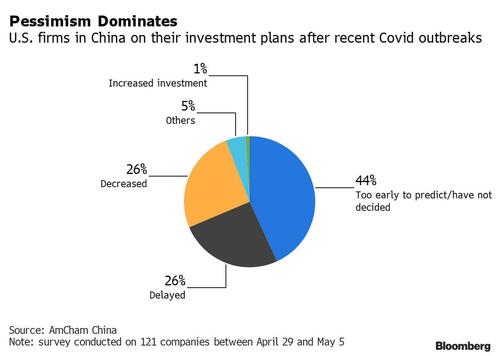

Trade wars, Covid and supply-chain disruptions were not on the minds of foreign executives back then. In 2022, however, 52% of 121 companies polled by the American Chamber of Commerce in China have either cut or delayed investments. With only 1% planning to increase local investment, authorities have a daunting task to boost foreign direct investment as long as China sticks to its Covid Zero strategy.

Anecdotal evidence suggests the local rich are also on the run. In Singapore, BNP Paribas’ Southeast Asia assets are growing in “single digits” whereas Greater China assets are in “high double digits,” according to Arnaud Tellier, Asia Pacific CEO of the French bank’s wealth management arm. CNBC reported that inquiries at an accounting firm in the city state about setting up family offices have doubled over the past 12 months, mostly from Chinese residents or emigrants.

Between 2014 and 2016, China’s FX reserves fell by almost $1 trillion as the onshore yuan lost more than 11% versus the dollar. With reserves barely above $3.1 trillion as of April, Beijing can not afford to draw down its dollar stash in a similar way. Raising interest rates is also out of the question given the dire economic situation.

As my colleague Ye Xie pointed out, the PBOC still has plenty of other tools to cushion any yuan free fall. And Russia’s experience with the ruble should give policy makers more confidence to dust off their playbook for capital controls. Back in 2016, regulators suggested to Deutsche Bank that it remit proceeds from a $3.9 billion stake sale in batches rather than in one go. More companies may soon have to face the same predicament.

By George Lei, Bloomberg Markets Live commentator and reporter

Strict capital controls made it impossible for several European companies to send dividends abroad and a Japanese beverage maker could not get paid due to “tougher restrictions on cross-border wire transactions.” This is not Russia in 2022, but China in late 2016 and early 2017, when the yuan plunged toward 7 per dollar.

Those types of curbs could soon be brought back as part of Beijing’s arsenal to manage currency depreciation, especially in a context similar to 2016-17: Once again, the Fed hikes and capital flees. Besides the headline exchange rate, how much and how quickly money can leave China will become equally, if not more, important.

Global portfolio managers, foreign businesses and the local rich are either leaving China or bringing much less capital onshore. The nation suffered an unprecedented outflow from bond and stock investors in March and net selling continued into April, according to estimates from the International Institute of Finance.

Total capital outflows, including errors and omissions, may surge to about $300b this year from $129b in 2021, IIF said in a report last week. While that figure is well below $725b, IIF’s estimate for 2016, Beijing’s options for combating it are much narrower this time around.

Trade wars, Covid and supply-chain disruptions were not on the minds of foreign executives back then. In 2022, however, 52% of 121 companies polled by the American Chamber of Commerce in China have either cut or delayed investments. With only 1% planning to increase local investment, authorities have a daunting task to boost foreign direct investment as long as China sticks to its Covid Zero strategy.

Anecdotal evidence suggests the local rich are also on the run. In Singapore, BNP Paribas’ Southeast Asia assets are growing in “single digits” whereas Greater China assets are in “high double digits,” according to Arnaud Tellier, Asia Pacific CEO of the French bank’s wealth management arm. CNBC reported that inquiries at an accounting firm in the city state about setting up family offices have doubled over the past 12 months, mostly from Chinese residents or emigrants.

Between 2014 and 2016, China’s FX reserves fell by almost $1 trillion as the onshore yuan lost more than 11% versus the dollar. With reserves barely above $3.1 trillion as of April, Beijing can not afford to draw down its dollar stash in a similar way. Raising interest rates is also out of the question given the dire economic situation.

As my colleague Ye Xie pointed out, the PBOC still has plenty of other tools to cushion any yuan free fall. And Russia’s experience with the ruble should give policy makers more confidence to dust off their playbook for capital controls. Back in 2016, regulators suggested to Deutsche Bank that it remit proceeds from a $3.9 billion stake sale in batches rather than in one go. More companies may soon have to face the same predicament.